God in the Bible is often presented as the preeminent, rather than exclusive, sky deity.

God is one, yes? Amen, we Christians, together with our Jewish and Muslim sisters and brothers, believe that. Catholics proclaim that in our Profession of Faith. Moreover, we believe there can be only one God in existence. But here is where we disagree with our Israelite ancestors in the faith found throughout the Bible. Here is where we have evolved theologically past the New Testament documents.

Monotheism took a long time to evolve. That may shock most Christians and Jews. After all, we’re often taught that Abraham was the first monotheist, Judaism is 4,000 years old and taught monotheism from the beginning, and that monotheism is readily seen everywhere throughout the Old and New Testaments. In spurious familiarity, people just accept that ancient Israelites were monotheists. But the reality is more complicated.

In truth, monotheism is rare in the Bible, if it is there at all. And even when it gets sighted in its pages, it is nothing like the severe monotheism featured in Islam and Judaism, or the Trinitarian monotheism that centers Christianity. To understand what I mean, watch the video carefully—

G0d, by way of Anachronism

Often people anachronistically think of ancient Israelites as if they were Jews, and hence, monotheists. They then distinguish the ancients like this—Israelites (biblical “Jews”) believed and worshiped only one God while Mediterranean non-Israelites (“pagans”) believed and worshiped many gods. In contrast, scholars convincingly demonstrate that the theological difference is significant. Historically, Israelites (neither Jews nor Christians) worshiped one and only one God in monarchy, and non-Israelite Mediterraneans (polytheists, not pagans) worshiped many gods in hierarchy.

Regardless of the specific Israelite or “Greek” cultural contexts and different labels used, common sky entities functioned everywhere throughout the Mediterranean. “Civilized” Hellenic Mediterraneans easily could identify Zeus and Jupiter and Yahweh as the same sky person or “most high god.” Israelites, despite denying the reality of other gods in statue-forms, accepted these pan-Mediterranean gods with all their features, but called them “archangels” and “angels.” No matter the significance of these different labels for shared sky persons, all believed like Paul—“there are many lords and many gods” (1 Corinthians 8:5). Does that sound like monotheism?

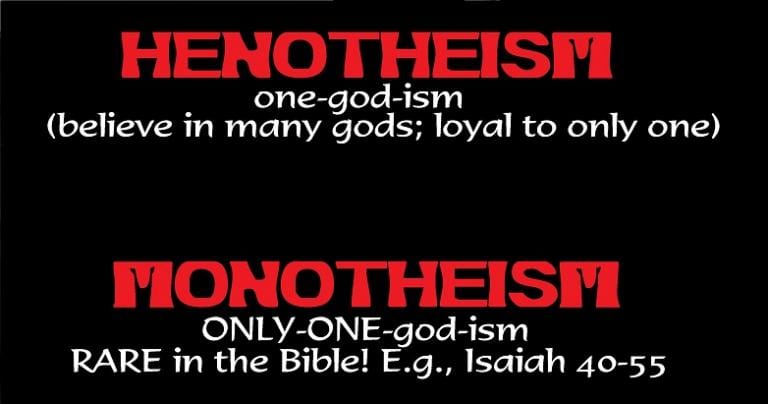

Our spurious familiarity with Paul and the world of the Bible and ancient “Jews” obfuscates reality. Israelites in the First and New Testaments did not really hold to monotheism. Rather, they were henotheists. What does that mean?

God: Monotheism VS Henotheism

Monotheism means “only-one-God-ism.” Henotheism, featured in Paul, throughout the New Testament, and the Hebrew Scriptures, means “one-God-ism.” Note the difference. A henotheist (e.g., Paul or John the Seer in Revelation) is loyal to one God existing in a hierarchy of many, many gods. It’s like being loyal to one ruler among many, many rulers. Unlike monotheism, henotheism accepts that different ethnic groups have their own patron deity or “supreme God.” Henotheists don’t deny the existence of other gods just as they don’t deny the existence of other ethnic groups to whom those gods patron.

This is one of the many reasons why Paul, John in Patmos, and all other New Testament personalities were neither Jews nor Christians. Christianity and Judaism, twin sisters, would later emerge from the womb in the fourth century. While Judaism and Christianity are related to Judaean and Hellene Israelite groups from the first century, surely, they are nevertheless distinct. Unless you wrongly imagine that monotheism is trivial to Christian and Jewish identity, this should be evident to you.

All Theology is Culturally Specific Analogy

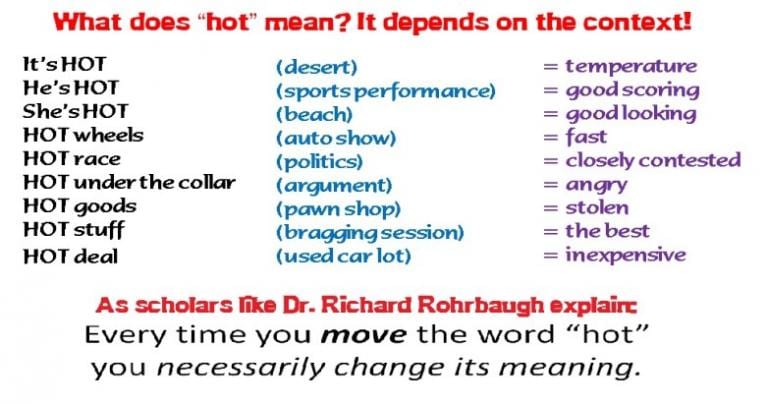

Context scholars Bruce Malina, Richard Rohrbaugh, and John Pilch remind us of a Medieval axiom and general cognitive principle held by St. Thomas Aquinas. It states that all theology is analogy. Think about that, deeply—everything we can know and say about God is analogy. And all analogy is rooted in human experience. The social sciences improve on Aquinas—all human experience is culturally specific. Ergo, all theology (God-talk) must be culturally specific anthropomorphic analogy.

The only way human beings can describe Holy and Absolute Mystery, the great “All” of Reality, is via drawing comparisons with human experience. This is so because the only thing we humans immediately and directly know is human! This also applies to whatever Albert Einstein, Carl Sagan, and Neil Degrasse Tyson know. If I know quarks and quanta, black holes and light years, cosmic background radiation and sunspots, it can only come by way of analogy with human experience.

Culturally Specific Henotheism

Let’s apply this general cognitive principle to the first century Israelite world of the Bible. Here we have a society permeated with henotheism. How did this happen? Going by the principle above, there had to exist a social structure in place used as an analogy for articulating said henotheism. This likewise explains the absence of monotheism in the Bible. More on that momentarily.

Consider the first century social institution and role of “lordship.” A Mediterranean “lord” is a male whose authority over persons, beasts, and all other objects in a given region is absolute. So then, what does it mean when the Greek translation of the Hebrew Scriptures calls the God of Israel “Lord,” or when the New Testament Jesus groups do the same for the resurrected Jesus? Analogy alert! Before anyone could call God or Jesus “Lord,” they needed an already existing social reality of Mediterranean “lordship.” The social reality had to first exist to serve as a meaningful analogy of what God and Jesus might be like! Otherwise, no one could call either “Lord.” Does that make sense?

When it came to seeing and expressing God, ancient Israelites looked to Near Eastern monarchy as the social structure to serve as a fitting analogy. This was especially true of what they saw in the Persian monarchy. Despite the fact that the Persian ruler was a king of kings, many other kings existed in their world. This is a good environment for maintaining henotheism.

God Seen through the Oldest Biblical Analogies

Notice how ancient Israelites understood God before the Persian influence came in, preserved in some very ancient Scriptural traditions. The God of Israel is presented as the king-god of a single ethnic group, and is a storm god (Judges 5:5, 21; 1 Samuel 12:18; 1 Kings 8:35) and a warrior god (Psalm 24:8). Other peoples had their own patron gods different than Yahweh (Judges 11:24). This is not monotheism, folks!

Before and during the New Testament period, Israelite rulers were confined to a single region and ethnic group. The analogies were therefore henotheistic. Hence henotheism, and not monotheism, is found everywhere in the Bible. Recall that henotheism means being loyal to one God among a plethora of other gods. This is culturally specific analogy taken from the experience of being loyal to one ethnic king among many kings. Just as we are subject to one king among many other kings, so too we are loyal to our ethnic God among many other ethnic gods—went Israelite thinking and custom.

Chosen People & God: Henotheism

Consider how the biblical expression “chosen people” comes from henotheism and not monotheism. There is one people among many other peoples chosen to be preeminent, and so too their God has preeminence over all other gods. Conveniently OUR GOD is supreme!—Yahweh or Elohim or Adonai (Lord) or Yahweh-Elohim depending on what stage we are in the evolution of naming.

Decalogue & Henotheistic God

“But the Ten Commandments demand monotheism!” Not really. To command “You shall have no other gods before me” (Exodus 20:3; Deuteronomy 5:7) presents henotheism, not monotheism. The first commandment does not insist on the uniqueness of the God of Israel. Rather, it insists on the God of Israel’s precedence and preeminence. There can be no other gods before (or after) this God, but there are other gods! The commandment implies that. This cannot be monotheism, folks.

The Shema is Monotheistic, Right??

What about the Shema, the Creed of Israel?

Hear, 0 Israel, the Lord our God is one Lord; and you shall love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your might!

See Deuteronomy 6:4-5; Matthew 22:37; Luke 10:27

Like with all language, the meaning of the creed of ancient Israel changed when the times and places in which it was recited, shifted. Language only means what it means where and when you use it. Many Jewish brothers and sisters praying the Shema today do so as severe monotheists, and “Israel” means something related to, yet different from, ancient biblical Israel. But when first century Israelites prayed the Shema, “Israel” meant a political religious reality, and it underscored henotheism in the polytheistic Mediterranean.

Paul, the henotheist, agrees—

1 Corinthians 8:5-6

Indeed, even though there may be so-called gods in sky vault or on earth—as in fact there are many ‘gods’ and many ‘lords’—but for us there is one God, the Father, from whom are all things and for whom we exist, and one Lord, Jesus Christ, through whom are all things and through whom we exist.

So from where did monotheism come? Find out in this followup post!