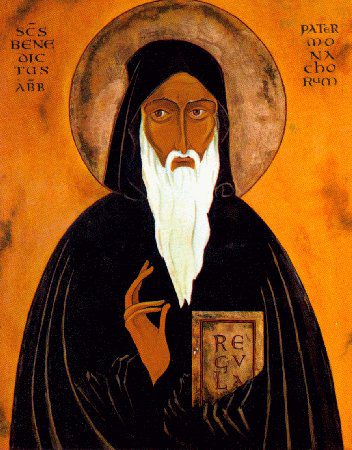

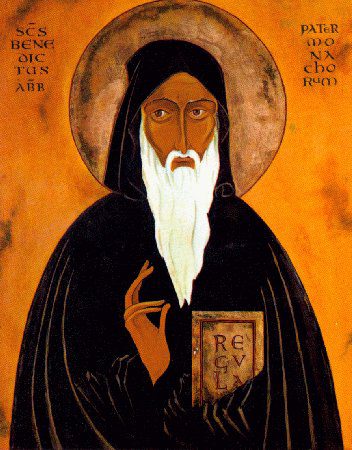

“Holy Scripture, brethren, cries out to us, saying, ‘Everyone who exalts himself shall be humbled,and he who humbles himself shall be exalted’ (Luke 14:11). In saying this it shows us that all exaltation is a kind of pride, against which the Prophet proves himself to be on guard when he says, ‘Lord, my heart is not exalted, nor are mine eyes lifted up; neither have I walked in great matters, nor in wonders above me'” (Ps. 131:1).

–The Rule of St. Benedict, Chapter 7

Just in case you assumed that St. Benedict and I would never have any arguments, I’m here to let you know that he and I don’t always agree. You would think that his chapter on humility would get me all gooey and weepy, that I’d be crying to myself about how far I have to go in the contemplative life. And, I probably will end up crying about my need for humility, but not because St. Benedict has inspired me to.

Chapter 7 lists 12 intense steps to humility. They’re not for the faint of heart and they include a lot of talk of hellfire and fear. See, his emphasis in Chapter 7 is heavy on on fear of hell directing the monks toward humility. It’s an emphasis that runs very close to self-hate, which doesn’t mesh with the kind of humility I see in Jesus.

The humility I see in Jesus is led by love. Love for the Father results in love for others. The kind of love for others that is sincere allows us to see the people around us (as Christ instructed) as Jesus himself. And that leads to action.

If Benedict and I agree on anything in Chapter 7 it’s that humble action leads to humility. If we want to get our minds off ourselves, then we sacrifice, we give up our comforts and offer ourselves. We serve with our hands. We cook for others; we wash dishes. We, as Benedict says, make the choice that, like Christ, “I have come not to do my own will, but the will of Him who sent me” (John 6:38).

Humility, then, becomes reality, seeing things as they really are: Not that we’re worthless, but that we are desperately beloved. We have been rescued by our creator, who became flesh and gave himself for us. So we, in our flesh, give ourselves away.

Oh, Benedict, I want to whisper to you that those 12 steps are wonderful, it’s just your motivation that’s off, friend. Humility is not born of fear but of joy.

In December 20th’s reading of Watch for the Light: Readings for Advent and Christmas, Brennan Manning shares a story of Saint Francis and Brother Leo walking down the road. Francis has noticed that Brother Leo is depressed and Leo has admitted to being overwhelmed of the work of “ever arriving at purity of heart.” St. Francis responds:

“Leo, listen carefully to me. Don’t be so preoccupied with the purity of your heart. Turn and look at Jesus. Admire him. Rejoice that he is what he is–your Brother, your Friend, your Lord and Savior. That, little brother, is what it means to be pure of heart. And once you’ve turned to Jesus, don’t turn back and look at yourself. Don’t wonder where you stand with him.

“The sadness of not being perfect, the discovery that you really are sinful, is a feeling much too human, even borders on idolatry. Focus your vision outside yourself on the beauty, graciousness and compassion of Jesus Christ. The pure of heart praise him from sunrise to sundown. Even when they feel broken, feeble, distracted, insecure and uncertain, they are able to release it into his peace. A heart like that is stripped and filled — stripped of self and filled with the fullness of God. It is enough that Jesus is Lord.”

After a long pause, Leo said, “Still, Francis, the Lord demands our effort and fidelity.”

“No doubt about that,” replied Francis. “But holiness is not a personal achievement. It’s an emptiness you discover in yourself. Instead of resenting it, you accept it and it becomes the free space where the Lord can create anew…Renounce everything that is heavy, even the weight of your sins. See only the compassion, the infinite patience, and the tender love of Christ. Jesus is Lord. That suffices. Your guilt and reproach disappear into the nothingness of non-attention. You are not longer aware of yourself. Like the sparrow aloft and free in the azure sky. Even the desire for holiness is transformed into a pure and simple desire for Jesus.”

Oh, that this Christmas we might renounce everything that is heavy and see in our newborn Savior “the compassion, the infinite patience, and the tender love” that changes us…the love that brings us to true and deep humility.