“The Lord has brought you out with a mighty hand and redeemed you from the house of slavery” -Deuteronomy 7:8

A new book, The Locust Effect, argues that stopping violence against the poor is fundamental to establishing a social order that promotes the common good and human flourishing. This issue is not simply a matter of compassion for the marginalized, as important as that is. Protecting the poor against enslavement, brutality, theft, and other forms of violence must be central to any serious integration of Christian faith with the world of work and economics. The moral commitments that mobilize evangelicals to fight human trafficking actually have a much broader application, and point to the possibility of a larger Christian vision for the public square.

The Locust Effect is by Gary Haugen, founder of one of the most important justice ministries in the evangelical world – the International Justice Mission (IJM). This organization aids the poor and marginalized who have been victims of violence and exploitation, and it has become especially prominent in the fight against human trafficking. While The Locust Effect is about more than just trafficking, many readers inevitably will focus on this one aspect.

These days, trafficking is the only public issue evangelical leaders are comfortable identifying as a gospel imperative. As a result, evangelicals are highly mobilized and accomplishing a lot. On every other public issue, however, we’re paralyzed by endless debates. There are no shared commitments, nothing we’re allowed to agree on; there is only division between the Right and the Left. So we produce a lot of heated rhetoric, and nothing gets done.

A few years ago, the Acton Institute inquired about holding an event on faith, work, and economics at an evangelical college. The school official told Acton that the event would have to be a debate, because “whenever we talk about public issues, we always have both sides presented.” Later in the conversation, the official mentioned that the school held a big event on human trafficking. “Oh?” said the Acton representative. “Who was your speaker in favor of human trafficking?”

Perpetual Division

This perpetual division over everything has to change if the gospel is going to speak to the culture, if Christians are going to have an impact in the public square, and if local churches are going to be forces for flourishing in their communities. The human trafficking issue proves there is a way out of this dilemma, because it shows that we do have shared moral commitments. The Locust Effect is a good example of how to apply those commitments beyond just trafficking. The Kern Pastors Network, the Oikonomia Network, and others who are working to integrate faith, work, and economics can carry these principles even further.

Bringing justice, dignity, and flourishing to a culture starts with upholding the equal dignity of all human beings. One thing this requires is that everyone’s rights of work, property, and exchange are equally protected. The Locust Effect makes this point in an introductory way, with a focus on the world’s poorest and most vulnerable populations. But these are not just truths about poverty; they are truths about what it means to be human and to live in a social order, so they apply to a much broader set of public questions.

We can see that breadth if we start with the issue where consensus already exists – slavery – and work outward. Slavery is the daily reality for millions around the world whose rights to work, property, and exchange are not protected. If you can force me to work – or not to work, as is often the case – you enslave me. If you can take away the fruits of my work at will, you enslave me. If you can take away my home at will, you enslave me. If you can arbitrarily prevent me from buying what I need, or selling what I make, in an open marketplace, you enslave me. This is exactly what the powerful do to the powerless every day around the world.

Historical Perspectives

Hernando de Soto, an economist whose work is cited in The Locust Effect, has extensively documented that one of the most central factors in poverty around the world is when equal rights for the poor in their work, property, and exchange are not protected. He sent graduate students to the world’s poorest areas to document conditions, and his work points to a dramatic conclusion: to a large extent, the poor remain poor because they are not allowed to work, save, and build anything for themselves. They are arbitrarily excluded from work and business opportunities, and if they ever do manage to save or build anything, it is simply taken away from them by the powerful. De Soto published this work in the landmark book The Mystery of Capital.

This is not a new idea. Abraham Lincoln understood these connections in a profound way. In order to delegitimize American slavery, he constantly talked about the sacredness of work, property, and exchange. He told Americans a story about the dignity of work, the meaning of work, the purpose of work, and how property and contract were a part of that story. The story Lincoln told Americans about the meaning of work was at least as important to the destruction of American slavery as his (equally profound) philosophical and legal arguments.

One of Lincoln’s best lines referred to slave owners as “men who eat their bread by the sweat of other men’s faces.” In 19th century America, audiences immediately recognized this reference to Genesis 3:19, and would have been familiar enough with the text to appreciate Lincoln’s devastating inversion of the biblical adjective (“by the sweat of your face you shall eat bread”; see also II Thessalonians 3:10). What I love about this line is how it weaves together the seamless connections between work (“sweat”), property (“bread”), and exchange (“other men’s”), showing how slavery is an abomination to justice in all three ways.

Other enemies of slavery saw the same connection to work and economics. One of my favorite historical figures is Josiah Wedgwood, an 18th century industrial pioneer known among evangelicals today because he used his fame and fortune as a porcelain manufacturer to fight slavery. What is less widely known is that he became rich and famous largely because he introduced dramatic reforms in the way factories were run. When Wedgwood arrived on the scene, factory owners had contempt for their workers, expecting little productivity out of them, and allowing them to live in scandalous conditions. Wedgwood saw workers as creatures with dignity who were capable of mastering their tasks and performing excellent work. He saw to it that his workers received decent housing and medical care; he ruthlessly cracked down on drunkenness and slacking, gave them responsibility for specific tasks, and set high standards for their work. His factories blew everyone else’s out of the water, and that’s why he had money and fame to lend to the anti-slavery cause. But it’s more important to notice that the same view of work and economics lay behind his factory reforms and his campaign to destroy slavery; they were not separate issues for him.

Wedgwood’s reforms helped create the modern, entrepreneurial economy we enjoy today. The single most important factor in producing the Industrial Revolution was what P.J. Hill, emeritus professor of economics at Wheaton College, calls the “Institutional Revolution.” Citing extensive new scholarship in this area, Hill argues that the key change that produced the modern economy was the transition from social orders that only protected the powerful, to social orders that aspired to protect the rights of all equally (however imperfectly that promise has been kept). As he explained in a lecture at last November’s meeting of the Evangelical Theological Society, “institutions that recognize the fundamental dignity and worth of all people are the basic reason for economic growth.” Establishing that everyone has the same rights to work, property, and exchange has been pivotal to justice and economic flourishing in the modern world.

Lessons

From all this, let me draw two lessons. First, the faith and work movement could make major contributions to the fight against human trafficking. Like Lincoln and Wedgwood, today’s anti-trafficking activists could gain huge advantages in delegitimizing slavery by telling a story about the meaning of work. The faith and work movement has the intellectual and personal resources to help tell that story.

The second lesson, though, is that it goes both ways. Just as the faith and work movement has something the anti-slavery activists need, The Locust Effect shows that anti-slavery activists have something the faith and work movement needs: the drive to apply our moral commitments to the social order, and not just to our personal lives. This is why The Kern Family Foundation is not just talking about faith and work, but faith, work, and economics.

If the church is against slavery, it must be for freedom – not anarchy or libertarianism, but “institutions that recognize the fundamental dignity and worth of all people,” in Hill’s fine phrase. If the church is not in favor of that, then in the long run, it’s not really opposed to slavery. When the faith and work movement says that all people are made to be stewards of the world, this implies we need a social order that treats all people as stewards – stewards of their own lives, stewards of their relationships with one another, stewards of the shared concerns of their civil communities, and stewards of the whole world, through the vast, global web of communication and exchange.

Over and over again the Israelites were reminded: “The Lord has brought you out with a mighty hand and redeemed you from the house of slavery” (Deuteronomy 7:8). Let’s follow his example and work for a social order that upholds the equal dignity of all people.

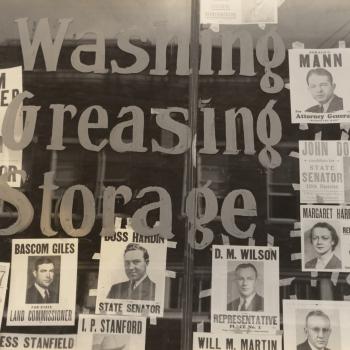

From the Kern Pastors Network. Image: KPN.