Recently Scott Samuelson, a community college professor, posted an article at The Atlantic under the provocative title “Why I teach Plato to Plumbers.” His argument is mainly about the importance of opening study of the liberal arts to all people, but it has important implications for integrating faith and work. He writes,

Recently Scott Samuelson, a community college professor, posted an article at The Atlantic under the provocative title “Why I teach Plato to Plumbers.” His argument is mainly about the importance of opening study of the liberal arts to all people, but it has important implications for integrating faith and work. He writes,

Once, when I told a guy on a plane that I taught philosophy at a community college, he responded, “So you teach Plato to plumbers?” Yes, indeed. But I also teach Plato to nurses’ aides, soldiers, ex-cons, preschool music teachers, janitors, Sudanese refugees, prospective wind-turbine technicians, and any number of other students who feel like they need a diploma as an entry ticket to our economic carnival. As a result of my work, I’m in a unique position to reflect on the current discussion about the value of the humanities, one that seems to me to have lost its way.

Why, he wonders, is education on the community college level assumed to be all about skills and not about thoughtfulness and growth?

Why shouldn’t educational institutions predominately offer classes like Business Calculus and Algebra for Nurses? Why should anyone but hobbyists and the occasional specialist take courses in astronomy, human evolution, or economic history? So, what good, if any, is the study of the liberal arts, particularly subjects like philosophy? Why, in short, should plumbers study Plato?

My answer is that we should strive to be a society of free people, not simply one of well-compensated managers and employees. Henry David Thoreau is as relevant as ever when he writes, “We seem to have forgotten that the expression ‘a liberal education’ originally meant among the Romans one worthy of free men; while the learning of trades and professions by which to get your livelihood merely, was considered worthy of slaves only.”

He admits,

As a professor with lots of experience giving Ds and Fs, I know full well that the value of the liberal arts will always be lost on some people, at least at certain points in their lives. (Whenever I return from a conference, I worry that many on whom the value of philosophy is lost have found jobs teaching philosophy!) But I don’t think that this group of people is limited to any economic background or form of employment. My experience of having taught at relatively elite schools, like Emory University and Oglethorpe University, as well as at schools like Kennesaw State University and Kirkwood Community College, is that there are among future plumbers as many devotees of Plato as among the future wizards of Silicon Valley, and that there are among nurses’ aides and soldiers as many important voices for our democracy as among doctors and business moguls.

But he also argues,

I once had a janitor compare his mystical experiences with those of the medieval Sufi al-Ghazali’s. I once had a student of redneck parents—his way of describing them—who read both parts of Don Quixote because I used the word “quixotic.” A mother who’d authorized for her crippled son a risky surgery that led to his death once asked me with tears in her eyes, “Is Kant right that the consequences of an action play no role in its moral worth?” A wayward veteran I once had in Basic Reasoning fell in love with formal logic and is now finishing law school at Berkeley.

The implications for the discussions we have here at MISSION:WORK are obvious. Striving to be a society of free people means helping people of all social classes to find meaning in their lives and work. And as Christians, we believe not only that that ultimate meaning is found in nurturing habits of mind and heart that will lead to right actions (often through struggling with difficult questions!) but also that the search for ultimate meaning has its roots in God, the Ultimate Source.

Yesterday in this space we published a reflection arguing that the faith and work movement needs to remember the needs, desires, and struggles of plumbers as well as philosophers. As you read Samuelson’s article, ponder how you can broaden the conversation. (And comment here. We’d love to hear from you.)

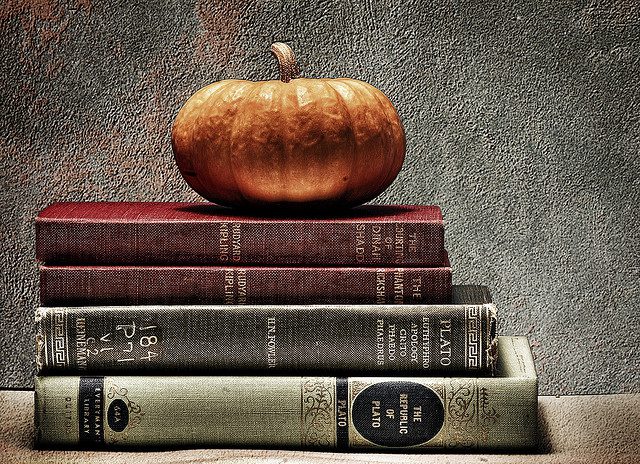

Image: “Still Life With Plato“ by Randen Peterson, used under a Creative Commons 2.0 License.