We recently ran a post talking about how Americans don’t take enough vacation. On the heels of that, Mark Galli of Christianity Today pointed us towards a helpful essay on the Christianity Today website called “Sabbath is Not a Means to More Productive Work.”

We recently ran a post talking about how Americans don’t take enough vacation. On the heels of that, Mark Galli of Christianity Today pointed us towards a helpful essay on the Christianity Today website called “Sabbath is Not a Means to More Productive Work.”

Author David Zahl begins by noting the huge market in the U.S. for sleep aids. The most interesting thing about that market, he says, is

how these items are being marketed. We are told that “for each additional 10 hours of vacation employees took, their year-end performance ratings… improved by 8 percent.” These products are not being marketed as aids to help us rest, but as widgets that will improve our performance at the office, or on the playing field, or in the bedroom, or whatever venue we value most.

The most effective way to sell sleep, in other words, is to make it constituent of work, handmaiden to productivity. Rest is no longer rest, just a prelude to more work. Thus the human being becomes a machine to be “optimized”, as the life-hackers transparently put it. Like a machine, our worth depends on our performance; it may even be synonymous with it.

Why is this, David wonders?

Some see these numbers as evidence of a superior work ethic. Others write them off as a dehumanizing but necessary byproduct of technological advances afforded by 21st century capitalism. Others still, and I would include myself in this number, wonder if something deeper is going on, if our collective over-occupation might be indicative of a pathological fear of boredom and, yes, death. Some would go so far as to say that work is a socially approved means of justifying our existence, of reminding us we are alive and allowing us to forget that we will die.

Whatever the case, what’s clear is that we do not know how to rest.

Well, that got me right between the eyes (as did another wonderful essay Mark Galli pointed out, about the value of being bored.) David goes on to point out that our “fundamentally restless culture” has swung the opposite way from the experience of Sabbath a few generations ago:

The current situation is a tad ironic. Talk to a member of the “greatest generation” about their childhood Sundays and they will invariably relate youthful frustrations about Sabbath prohibitions. They will tell about blue laws. About no baseball on Sunday. No movies. No shopping. To most of them, Sabbath did not represent an oasis of inactivity—it represented a resounding No, an inflexible Law put there to confound fun and frivolity. They describe an environment where what was intended for good had hardened into a mode of control and repression—legalism, if you will. The spirit had been lost, as it often is.

Today, the zeitgeist has shifted. What was once prohibition might now be heard as permission: to stop, take a breath, and remember that we are more than what we produce, more than our job title or bank balance. Sabbath, in this light, does indeed represent resistance to the dominating paradigm of more more more, an invitation to, well, the experience of grace.

But just saying “rest” to workaholics isn’t enough (I can vouch for this one):

That is to say, as tempting as it may be, a louder, more articulate expression of divinely mandated rest will not inspire repose in those for whom work and ‘doing’ has become integral to their self-justification—which is all of us.

I can’t help but think about all the times when I’ve been told to “just relax.” Suffice to say, relaxation was not my first reaction. I mean, try telling a workaholic to stop working so hard. Often, they’ll give you a litany of reasons why scaling back isn’t an option. They may even do what many well-meaning Christians do: embrace the Sabbath while dodging its existential punch, i.e. find another, more ostensibly holy (or pleasurable) pursuit to occupy them on their day off.

Instead of following recipes for relaxation, the answer (ouch!) lies in the harder, but paradoxically also easier, task of following Christ:

Perhaps the late, great Episcopal theologian Robert Capon put it best when he wrote, “if the world could have lived its way to salvation, it would have, long ago. The fact is that it can only die its way there, lose its ways there.” As much as we might wish it were so, the answer to internal restlessness—mine and yours—cannot be found in a new (or old!) recipe for godly living. Our hope lies in the same place it always has, not just in the God of Rest, but in the God of the Restless, the God who welcomes the weary and heavy laden, and whose glorious passivity on the cross justifies inveterate lawbreakers of all stripes.

Amen! And we’d love to be of help on the journey. (You might like to check out a recent post, and another, on The High Calling about Sabbath, too.)

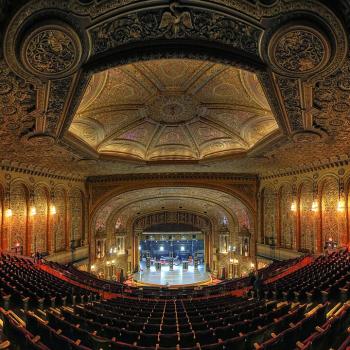

Image: “Bells” by Robert Terrell.