We’re returning to our occasional series of posts on work and vocation (linked at the bottom of this post) in Christian history by Faith and Work Channel senior editor and Christian History magazine senior editor Chris Armstrong. Enjoy!

We’re returning to our occasional series of posts on work and vocation (linked at the bottom of this post) in Christian history by Faith and Work Channel senior editor and Christian History magazine senior editor Chris Armstrong. Enjoy!

Having laid a biblical basis for thinking about work, I’d like to take us now on something of a whirlwind tour through some of the different ways the historical church has viewed work, vocation, and economics.

Is there a theological tradition, rooted in Scripture and passed on through the ages of the church, that affirms “secular,” even menial economic work is part of a larger picture of God-given vocation?

In a word, yes.

Of course, in the New Testament God’s primary call to the church is to preach and disciple. Yet, says Max Stackhouse, “many passages also recognize that people have earthly obligations, and the calling is closely identified with one’s responsibilities in life, which one is to fulfill dutifully.” He mentions 1 Corinthians 7:20 and Philemon as two examples. What we do not find in the New Testament is any general call for Christians to withdraw from participation in everyday life and economic work. Jesus does call a few fishermen to leave their nets, but this is clearly a special call for a specific few, limited to the time of his ministry on earth. Many others who believed in Jesus did so while continuing their work as soldiers, tent makers, purveyors of purple, and so forth.

Professionalizing “vocation”

At first, the understanding of vocation was that everyone is called to both salvation and service, without a clergy-laity divide. Eventually, however, the role of clergy grew as one of special function and authority. By the time Constantine moved Christianity toward its status as the official religion of the Roman Empire in the early 300s, “vocation” was applied to clergy, on the analogy of the holy, set-apart priesthood of ancient Israel. The distinction was strengthened in the 11th century, when Western clergy were mandated to celibacy—and thus separation from the ordinary life of family and business.

The most influential thinker in Western Christianity, Augustine of Hippo, distinguished between two spheres of human endeavor: the “active life” and the “contemplative life.” Augustine included in the active life all the ways humans serve one another—farming, crafting, trading, raising families—one might call this the “horizontal” dimension of life. The contemplative life turned the focus Godward, in prayer, worship, and spiritual disciplines—the “vertical” life. While both kinds of life were good, the contemplative life, pursued to some degree by clergy and with full commitment by monastics, was of a higher order.

So “having a vocation” came to mean becoming either a minister or a monastic. Os Guinness labels the ensuing two-class system “the Catholic distortion.” He criticizes it as dualistic, meaning that it separates spiritual things from earthly things, and thinking from doing. Guinness also identifies a later “Protestant distortion,” which has completely secularized the terms “vocation” and “calling”—such that these now become bare synonyms for simply having a job.

The Incarnation

But even in the early and medieval church, we will find important theological resources for thinking about economic work—resources that both Protestants and Catholics are in danger of losing.

The appearance of Christ on the scene as a human being, with all the physical needs, skills, and temptations we all share means that the church must not fall into the error of the Gnostics, calling the material world evil and thus assuming God is not active in our interacts with the material world. When we reflect on the unity of the Incarnation, we see that just as God joined divinity and humanity to work in time and space in the embodied Jesus, so he continues to work in our own times and spaces. To be true followers of the Incarnate Christ, we cannot ignore any sphere of our time-bound, material existence—least of all our work. In the words of modern Reformed thinker Abraham Kuyper, “There is not a square inch in the whole domain of our human existence over which Christ, who is Sovereign over all, does not cry: ‘Mine!’”

Originally published at Grateful to the Dead.

Previous posts in this series:

- Getting the beginning and end of the story right

- We were made to work

- Jesus the incarnate worker God

- A brass-tacks, real-world theology of work

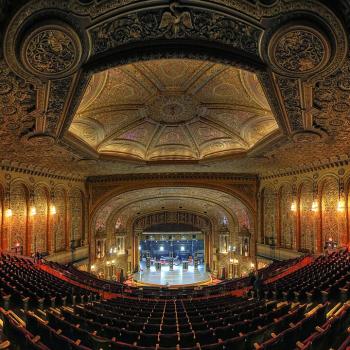

Image: Wikimedia Commons.