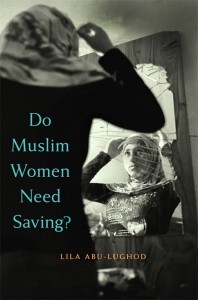

Editor’s note: Many of us at MMW have previously cited Lila Abu-Lughod’s 2002 article “Do Muslim Women Need Saving?” in some of our blog posts, and we were excited to see the recent release of her book of the same title. This is the first of a series of responses to the book by a few different MMW writers.

In the introduction to her recent book Do Muslim Women Need Saving?, Lila Abu-Lughod writes: “I am often bewildered by what I read or hear about ‘the Muslim woman’” (4). For those of us who share this sentiment, Abu-Lughod’s book is essential reading. Framed as “a long answer to the question of whether Muslim women have rights or need saving,” (201) the book builds on an essay that was first published in 2002. The fact that, more than a decade later, the need exists to continue to provide answers to such questions stems out of what Abu-Lughod describes as a “new common sense” which takes up the issue of “Muslim women’s rights” as though “there is something that unites all Muslim women or makes their lives and access to rights unique” (147). As she points out:

“when you save someone you imply that you are saving her from something. You are also saving her to something…. what presumptions are being made about the superiority of that to which you are saving her?” (47).

Early on in the book, Abu-Lughod mentions Muslimah Media Watch, describing Fatemeh’s post about a German human rights campaign poster that renders women as mute garbage bags. In asking “why so many, including human rights campaigners, presume that…Muslim women are not agentic individuals” (9) and why, to use a Bushism, “women of cover” are seen as unable to speak for themselves, the first few chapters of the book describe the “new common sense” and investigate how the current moral crusade to save Muslim women is authorized. Here Abu-Lughod provides her own perspectives on the well-covered ground of gendered orientalism and connections between feminist liberal discourses, and the colonial feminism of earlier eras.

This half of the book concludes with a chapter addressing “honor crime.” Abu-Lughod looks at how this issue is dealt with in political and legal battles in Muslim majority countries, pointing out the irony of populist Islamist politicians attempting to prevent reforms in Jordan by describing them as undermining tradition, when the laws to be changed are a blend of the Napoleonic Code, Ottoman law and British common law. In Western contexts, Abu-Lughod looks at how “the honor crime” has become a culturalized category of abuse, distinct from any other form of violence against women explained through reference to individual perversion rather than culture. For Abu-Lughod, the assumption of the uniformity of a certain form of violence as a timeless cultural practice affixes “values of individualism, freedom, humanity, tolerance and liberalism neatly onto the west while denying them to others” (128). In one of sections which most reveal this book to be one written by “An Anthropologist in the Territory of Rights,” Abu-Lughod contrasts the representations of “honor” as a cultural problem in popular narratives associated with Muslim women’s rights discourse, with her own experience living with a Awlad ‘Ali Bedouin community, where honor was part a widely shared complex moral code that affected both men and women.

Citing Ayaan Hirsi Ali’s Nomad, subtitled “a journey from Islam to America,” Abu-Lughod remarks, “this is an odd phrase…Islam is not a place from which one can come” (69) and notes that what is conjured up here is an “Islamland” inhabited by what Ali calls “the others…still locked in the world I have left behind” (74). Analyzing the consistent resort to cultural explanations, Abu-Lughod shows the ways in which nonfiction about “the abused Muslim woman” is related to the common sense that links itself to the language of human rights.

As M. Lynx Qualey notes in her recent post about Abu-Lughod’s book:

“This genre in many ways overshadows, and shapes the reception of, Arabic literature (in translation). A quick search of US libraries will turn up far more Nonie Darwish than Mahmoud Darwish.”

Books such as Nicholas Kristof and Sheryl WuDunn’s Half the Sky and Kwame Anthony Appiah’s The Honor Code may be “gentler in their politics” than Ayaan Hirsi Ali’s work, but Abu-Lughod argues that they share the same certainties: “they identify with the moral we who know what’s wrong with the world and must do something about it,” and despite offering disclaimers to disavow direct blame of religion, they “agree that Islamland is the place where things are most wrong today” (69). For Abu-Lughod, these are adjacent discourses which reveal the increasing blurring between the discourses of progressives and right-wingers on the issue of “Muslim women’s rights.”

When the authors of Half the Sky speak of “testosterone-laden values” (70) and include a chapter with the title “Is Islam Misogyinistic?” their referent for the universal is an idealized liberal democracy, building on a polarization granting “western society and well-integrated immigrants…a monopoly on liberal and human values” (125). This writing is centered on westerners as agents of change even if, to quote the authors of Half the Sky, this happens not by “holding the microphone at the front of the rally but by writing the checks” (63).

Abu-Lughod argues that such moral campaigns join a chorus that includes many dedicated organizations, academic conferences, and charitable foundations which address the issue of “Muslim women’s rights” and which ask us to be responsible global citizens, for example, The AHA foundation which asks us to “shop honor” by giving a donation of $50, for which you receive “a pretty, 3/4 inch in diameter, sterling silver necklace” with a spark which “symbolizes freedom, new ideas, and optimism for the future.”

But as Abu-Lughod writes, justice is not just “a click away.” The last two chapters move beyond describing and analyzing the new common sense to examining the dilemmas for activists in terms of the governmentalization of rights, state feminism, and the accomodation of religious discourse, as well as going into the commercialization of the rights discourse in addressing how much fund-raising and career-building takes place around “Muslim women’s rights.” Looking at organizations such as Sisters in Islam, WLUML, Musawah and her own positive experience with WISE, Abu-Lughod argues that while “political or strategic uses of dialects of rights have enabled political and moral gains…for disenfranchised groups and individuals,” there is a need to think about what the language of rights excludes and “to recognize its links with institutions and political configurations” (180). Insisting on the “inescapable politics” of particular contexts, Abu-Lughod gives the example of the Global Campaign to Stop Killing and Stoning Women, and points out that the period when the campaign was launched in 2007 was a period of great violence against women, not only in Iraq but also in Gaza – a striking example of the selective rendering of women’s rights in the region.

Abu-Lughod repeatedly returns to “how to think about choice and what it means to assert freedom as the ultimate value” (18), for example in a section entitled “Confounding Choices” in the introduction, which speaks about the limits of agency experienced by all individuals, since we are all born into social worlds. Towards the end of the book, she returns to the issue of choice as always restricted, always intertwined with power, and argues that choice has been “fetishized and defended in order to uphold for individuals the fantasy of being autonomous subjects” to an extent that ignores what Judith Butler has described as “forms of proximity, of living with, of adjacency and cohabitation that are radically unchosen” (218). I found these passages on the understanding of consent and choice to be some of the most compelling parts of Abu-Lughod’s argument. As Abu-Lughod herself notes, the issues of consent, agency and autonomy “lie at the heart of the matter” (18), and so it would have been useful to have these interspersed sections on choice consolidated into one chapter.

Aside from this minor criticism, I found Abu-Lughod’s book to be an engaging intellectual discussion (written in an accessible, blissfully jargon-free style) on the issues we at Muslimah Media Watch are concerned with on a daily basis. The question of the title, “Do Muslim Women Need Saving?” (like the equally problematic and widespread question “Is Islam a religion of peace?”) reveals the anxieties and perspectives that frame the discourse identified in this book as the “new common sense.” Abu-Lughod’s “long answer” to the titular question is a compelling call for nuance, and the rejection of “deceptively simple responses to problems we think we already understand or believe we should act on even before we understand” (226).