On April 30th the Jaafari Personal Status Law will be voted on in the Iraqi Parliament. The Jaafari Law, as it’s being referred to, has been controversial because it would enable Shia men to marry girls as young as 9 years old. Whereas the legal age for marriage in Iraq is 18 years of age, the Jaafari Law does not state an age limit for marriage, but spells out the divorce conditions for girls who have reached the age of 9. This piece of legislation, nonetheless, would also legalize marital rape by embedding into law that wives must comply with their husband’s sexual requests. Similarly, the law will affect issues of guardianship (restricting women’s mobility), and it favours fathers in custody issues if the children are older than 2 years of age. The bill is said to target Shias, whose electoral support is considered to be primordial in the upcoming election. Such a statement implies that Shias are the primary supporters of such restrictions on women.

Needleless to say the Jaafari Law has attracted considerable media attention and has sparked on-line mobilizations to stop the motion. Human Rights Watch released a call to stop the bill from being passed. The Iraqi Civil Society Solidarity Initiative launched a campaign for the same purpose. Walk Free, Care2 and Take Action feature on-line petitions to collect signatures against the bill (these can be accessed through the links).

The law shows the complexities of religious accommodation and how religion is utilized for political purposes. In a recent Al-Monitor article, Mushreq Abbas points out that Article 41 of the Iraqi Constitution stipulates that “Iraqis are free to abide by their personal status according to their religions, sects, beliefs or choices, as regulated by law.” This statement, which is meant to accommodate a variety of religious denominations, is being used to justify the Jaafari Law. However, Abbas also notes that the Constitution states that, “No law may be enacted that contradicts the established provisions of Islam” (Article 2, paragraph A).

The question that is left for interpretation is, whose Islam?

Whereas the Iraqi Justice Minister, Hassan al-Shimmari, has been quoted as saying that the Jaafari Law would prevent women’s abuse by regulating child marriage (currently existing but unregulated), passing such a law will entail an important setback in women’s rights in the country. In addition, it will not help regulate existing child marriages because the law does not entail provisions to empower women to seek divorce, child custody or protection from abuse. In short, the law does nothing to protect girls and women in forced marriages, and it does not regulate the unregulated.

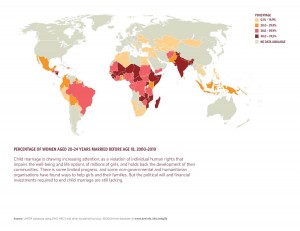

The Jaafari Law is a political move; yet, no answers have been provided as to who will benefit from this law. Some of the coverage of the issue indicates that Shia men will be the primary beneficiaries; however, I wonder, how many Shia men are looking to marry underage girls or have their daughters betrothed to older men in settings where they can be coerced into sex? Whereas these situations exist, and not only in the Arab world, UNICEF makes a point of saying that, “Child marriage is also a strategy for economic survival as families marry off their daughters at an early age to reduce their economic burden.”

It ihas been reported that child marriage rose after the American occupation of Iraq, and although sources like the Washington Post attribute child marriage to tradition, it is well-known that conflict and war bring along gender-based violence and institutions that, even if non-existent before, affect women in particular ways. According to Girls not Brides child marriage is most prevalent among the poorest countries in the world; their site offers little information on the prevalence of child marriage in Western countries.

A lot of the discussion over the issue has neglected further investigation into child marriage in the country, and the rise of the phenomenon post-conflict. Such an approach neglects important facts necessary to further explore the situation of girls and women in Iraq. For instance, we disregard the effects of more than a decade of American occupation on gender equality, which in itself would entail some kind of accountability on the issue at hand. Furthermore, we limit the description to talk about Shias without specifying among which groups is child marriage most prominent and the reasons behind it. Whether poverty, custom, tradition or politics are at the heart of the matter it is essential to investigate the roots of this phenomenon, because otherwise we can’t predict the effects of the law (or simply the discussion about the law) will affect vulnerable girls and women.

However, if embedded in law, the proposed bill will shut down these discussions, particularly because policy and laws are never neutral. This is why the efforts to avoid the institutionalization of child marriage, marital rape and custody inequities is so important. Yet, moving forward, we need to recognize that child marriage exists around the globe, and that conflict is a primary driver of gender inequalities. Then we are left with the questions, who is accountable and how do we move forward?