Some years ago I wrote something and in it referenced the term “liberal religion.” One reader, a theologically trained person, in fact a Roman Catholic priest, wrote to me that he was concerned that a political term like “liberal” would be attached to that word “religion.” He thought it an unfortunate pairing of terms.

I was surprised that he was unaware that the term liberal religion is a long established descriptor for a style of spirituality and a marker for several strands of Western religion. And, in fact, today this is also an appropriate descriptor for some religions from the East, and not exclusively for their Western manifestations.

Specifically, in the light of the rise of Buddhist Modernism, I think having some sense of that term “liberal religion,” how it came about, and what it means, might be helpful to those engaged in that conversation, sometimes debate. And it might be interesting to others, as well. So, here you go.

Liberal religion has several distinctive marks: it has a naturalistic bias and engages the truth claims of the tradition, whatever that tradition might be, critically. An early alternative term was “rational religion.” This spiritual approach brings an emphasis on rationality, naturalism, and, a broad humanism. While it originates within the Christian tradition there are currents of liberal religion in perhaps all established religious traditions. As I’ve already noted, including Buddhism.

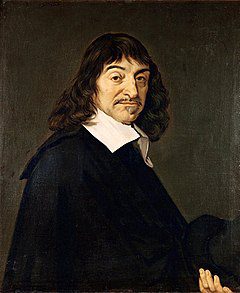

While there are antecedents to liberal religion throughout history, it emerges as a coherent approach in Europe and the Americas in the middle of the Eighteenth century. The Encyclopedia Britannica article on Theological Liberalism (a highly recommended read) suggests it basically starts with Rene Descartes in the Seventeenth century.

“In designating the thinking self as the primary substance from which the existence of other realities was to be deduced (except that of God), Descartes initiated a mode of thinking that remained in force through the 19th century and laid the ground for the presuppositions of this modern consciousness: (1) confidence in human reason, (2) primacy of the person, (3) immanence of God, and (4) meliorism (the belief that human nature is improvable and is improving).”

Other significant figures in this forming period would include Gottfried Leibniz, John Locke, Samuel Clarke, and my personal favorite of the lot, Baruch Spinoza. However, it doesn’t end there. Liberal religion would continue to evolve from the late Eighteenth century and well into the Nineteenth, in this period influenced by the rise of Romanticism. As the Encyclopedia Britannica article tells us, through an assertion of “the uniqueness of the individual and the consequent significance of individual experience as a distinctive source of infinite meaning, this premium upon personality and upon individual creativity exceeded every other value.”

In the Americas this would result in the rise of Unitarianism, Universalism, and particularly with the rise of the Romantic influence within Unitarianism, Transcendentalism. But the influences of this rising liberal religion could be seen throughout American Protestantism, as well as among some Catholics.

And there is a third evolutionary phase to liberal religion. Starting in the middle of the Nineteenth century two things happened. First, the rapid advances in science and particularly the work of Charles Darwin and others who upended generations of assumptions about natural history as presented in the Bible. Second, Modernism, a term first associated with a critical and humanist approach within the Catholic Church, also began to inform liberal religion. As that article in the Britannica notes, this led to a revolutionary approach. “A determined course emerged among Modernists to bring religious thought into accord with modern knowledge and to solve issues raised by modern culture.” In short, humanism.

So, this approach to religion derived from the European Enlightenment, washed through the Romantics, and then modern scientific and humanistic approaches to life writ broadly, after marking Christianity gradually began to influence other religions. For instance, when Reform Judaism emerged at the end of the Nineteenth century many of the founders called their community “liberal Judaism.” One liberal religious tradition with roots in Christianity, Unitarian Universalism has moved sufficiently beyond the truth claims, and maybe more importantly, the symbols of normative Christianity that many, both observers and from within, argue it is no longer a Christian religion. Others, both observers, and from within, disagree.

The incursions of modernity across the globe has included with it the seeds of liberal religion. And so, as the Wikipedia article on “religious liberalism” tells us today some “Examples of liberal movements within Islam are Progressive British Muslims (formed following the 2005 London terrorist attacks, defunct by 2012), British Muslims for Secular Democracy (formed 2006), or Muslims for Progressive Values (formed 2007).”

And most critically, while “Eastern religions were not immediately affected by liberalism and Enlightenment thought…” Nonetheless, in the wake of contact with Western philosophical positions, particularly in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth centuries, those same spiritual dynamics birthing Christian liberal religion have birthed a number of liberal religious expressions. Including a range of “Hindu reform movements (that) emerged in British India in the 19th century.”

Additionally, the article tells us “Buddhist modernism (or “New Buddhism”) arose in its Japanese form as a reaction to the Meiji Restoration, and was again transformed in the United States of America from the 1930s, notably giving rise to modern Zen Buddhism.”

While I’m sure a number of contemporary Zen Buddhists would disagree with that last characterization, I think it is arguable. And I can go a bit farther. I do believe that Zen Buddhism, possibly together with the emerging Western Vipassana movement, are the most modernist influenced Buddhist traditions. The Wikipedia article on Modernist Buddhism tells us:

“Buddhist modernism (also referred to as Modern Buddhism, modernist Buddhism and Neo-Buddhism) are new movements based on modern era reinterpretations of Buddhism. David McMahan states that modernism in Buddhism is similar to those found in other religions. The sources of influences have variously been an engagement of Buddhist communities and teachers with the new cultures and methodologies such as “western monotheism; rationalism and scientific naturalism; and Romantic expressivism”. The influence of monotheism has been the internalization of Buddhist gods to make it acceptable in modern West, while scientific naturalism and romanticism has influenced the emphasis on current life, empirical defense, reason, psychological and health benefits.”

While I would argue with the article’s list of what consists of modernist Buddhists, I think the article makes a compelling argument in its “overview” section.

“Buddhist modernism emerged during the late 19th-century and early 20th-century colonial era, as a co-creation of Western Orientalists and reform-minded Buddhists. It appropriated elements of Western philosophy, psychological insights as well as themes increasingly felt to be secular and proper. It de-emphasized or denied ritual elements, cosmology, gods, icons, rebirth, karma, monasticism, clerical hierarchy and other Buddhist concepts. Instead, modernistic Buddhism has emphasized interior exploration, satisfaction in the current life, and themes such as cosmic interdependence. Some advocates of Buddhist modernism claim their new interpretations to be original teachings of the Buddha, and state that the core doctrines and traditional practices found in Theravada, Mahayana and Vajrayana Buddhism are extraneous accretions that were interpolated and introduced after Buddha died. According to McMahan, Buddhism of the form found in the West today has been deeply influenced by this modernism.”

For me a critical point in that paragraph is that word “co-creation.” Could Buddhism evolve a modernist approach without Western influences? Of course. A point that Justin Whitaker’s insightful review of David McMahan’s magisterial The Making of Buddhist Modernism underscores. And, rightly so. That said, in order to have a comprehensive grasp of the subject, this book is a must read. Although I would add to Justin’s cautions my own caveat that Professor McMahan does not address the question of liberal religion, which I believe is critical to the questions of how the assumptions of modernity in fact become Buddhist assumptions.

In studying the emerging of modernist Buddhism I think it critical to avoid two excesses. The one is “Orientalism,” a belief that reforms within Buddhism had to come from the West due to some deficiency in the tradition. The other is creating a firewall and denying any sort of connection across traditions. Me, I believe the fact on the ground is that there were in the nineteenth century some significant encounters. And, it is hard to believe there wasn’t some kind of feedback loop happening. In fact that seems pretty obvious, particularly if we don’t try to find an exact one to one meeting, like a Theravada monk reading Descartes in the middle of the Nineteenth century, but rather where the atmosphere that births liberal religion also influences the Buddhisms arising in the West and the feedback loops to the original source communities. This all noted, the article continues.

“Buddhist Modernist traditions are reconstructions and a reformulation with emphasis on rationality, meditation, compatibility with modern science about body and mind. In the modernistic presentations, Theravada, Mahayana and Vajrayana Buddhist practices are “detraditionalized“, in that they are often presented in such a way that occludes their historical construction. Instead, Buddhist Modernists often employ an essentialized description of their tradition, where key tenets are reformulated in universal terms, and the modernistic practices significantly differ from Asian Buddhist communities with centuries-old traditions.”

So, the bottom line here. If we want to understand Buddhist modernism, there is little doubt we need to be familiar with the currents of liberal religion. How they tangle is not clear. That they do, is.

What is emerging I find exciting. Healing possibilities for the whole of humanity.