What if? Walking the Silk Road and finding a Luminous Religion

James Ishmael Ford

(I’ve explored the mysteries of Buddhist Christianity any number of times. I’ve especially found myself pulled to that Daoist/Buddhist Christianity called the Luminous Religion. Here I gather together at least some of those ruminations, brush them off, suture them together, polish some of the rougher edges and find I’ve come up with a sermon. Delivered today, the 1st of September, 2019, at the Unitarian Universalist Church in Anaheim, California.)

Okay, I’m a sucker for those historical “what if” kind of things. You know, what if the Spanish Armada defeated the English, or what if the South had won the Civil War, or the Nazi’s the Second World War. Read a lot of books on those themes in my younger years. Books like Robert Silverberg’s Roma Eterna, and Philip K Dick’s Man in the High Castle.

Admittedly, I haven’t followed the literature over the years. For whatever reasons, my taste in light reading has shifted from science fiction to mysteries. Still. People have been telling me for quite a while now I have to read Kim Stanley Robinson’s The Years of Rice and Salt, where the plague takes away ninety nine percent of Europe’s population instead of a third, leaving the world to be shaped by Muslim, Chinese, and indigenous American cultures. I do like the idea. And I gather the treatment is more haunting than Silverberg’s The Gates of the World, with a not quite so devastating plague.

Of course, my favorites of such things are religious, or, at least have a religious thread. Kind of obvious, I guess. Which I’m sure is in part why people keep pointing me to that Years of Rice and Salt. And, so, of course, why one of my favorite books in recent years is Michael Chabon’s The Yiddish Policemen’s Union, which posits a world where Israel didn’t happen, and the Jewish community makes a temporary home in Alaska.

However, today I’d like to hold up the intriguing realities of Eastern and Western religious encounter and speculate just a little on some of the “what ifs” that with just a few things going one way rather than another could have left us with a very different Christianity. Or, at least, a very interesting and vibrant alternative possibility to what has become normative.

Perhaps you’ve heard of Sts Barlaam & Josaphat. It’s the story of prince Josaphat and his conversion to the true faith through the guidance of the hermit Barlaam. It appears in the West in the eleventh century, apparently composed by the monk Euthymios, although attributed to the seventh century John of Damascus. In fact, the story is quite a bit older than either the eleventh or seventh centuries. And continuing variations of that story pop up all over the place, from the Golden Legendto a walk on in Shakespeare’s Merchant of Venice. The theme is what one may call a classic.

The prince Josaphat and the holy Barlaam were celebrated as saints with official feast days in both Catholic and Orthodox churches. However, in the nineteenth century scholars realized the true source of the story. The name Josaphat derived ultimately from the Sanskrit and means bodhisattva, “enlightenment being.” Eventually those hard working scholars figured out the story, through some interesting turns, was really all about the Buddha. And the saints were quietly removed from the official calendar.

I do love that.

While we can say with near certainty that Jesus himself never visited Tibet, or even India, there was in fact lots and lots of cross fertilization between East and West. Ideas and people followed that Silk Road in both directions and for a very long time.

So, of course the story of the Buddha would make it West, even if only as a faint echo. But, what about the other direction? We know Christianity made it as far as India. That church exists to this day, or, at least its descendant organizations. But, what about ancient China?

Well, it should not be much of a surprise how in 1625 workers digging near a temple in Xi’an in Northwest China, discovered a large stone monument. Local intellectuals, more scholars, began to examine it and discovered it recorded the story of a long-lost Christian mission to China. Written in Chinese and Syriac it recounted the early Seventh century mission of Bishop Alopen and the establishment of the “Luminous Religion,” a Chinese branch of the Church of the East, sometimes called the Nestorian Church.

What’s particularly interesting is how the tablet’s Christianity doesn’t quite line up with Nestorian orthodoxy. And in some interesting ways. The trinity, for instance, is mentioned, as is the incarnation. But there’s no reference to a crucifixion or resurrection. It was also clear that the Luminous Religion had synthesized with both Buddhism and most of all with Daoism.

All so tantalizing, but just this one large stone monument left as testimony to something long gone. It appeared that during the Great Anti-Buddhist Persecution in the middle of the Ninth Century, while it knocked Buddhism back on its heels, the persecution also wiped out several smaller religious communities. Including the Luminous Religion, which apparently the authorities considered a Buddhist heresy. A factoid I find delicious. What the Luminous Religion actually was remained a marvelous hint at something. But what that something was, no one was sure precisely sure.

Then on the 25th of June, in 1900, near Dunhuang, an ancient Chinese city along that Silk Road, a Daoist monk stumbled onto a cache of manuscripts hidden in a cave. This discovery ranks at least with finding the Dead Sea scrolls and the Nag Hammadi library. I suggest as relates to world culture this discovery is more important.

The caves, it turned out there were a number, ultimately proved a treasure trove of documents. Some fifty thousand of them, written in fifteen different languages, including at least one language that has otherwise been lost to the sands of history.

Some of the Daoist and Buddhist texts are priceless. They deeply re-orient a world of scholarship. For me the early edition of the Platform Sutrawhat can be considered the foundational document of the historic rather than mythic Zen school is enormously important. The cache also included the oldest printed book in the world, an edition of the Buddhist Diamond Sutra.

And – it included texts from that long-gone Luminous Religion. Some scholars name the cache the “Nestorian documents.” Prosaic, but accurate enough. However, noting the title used by some of the texts themselves, many call the collection the “Jesus Sutras.”Sutra means thread and is used in the sense of our shared Indo-European English’s “suture,” a binding thread. In Buddhism a Sutra is a sacred text. And while Christian, the shifts from normative Christianity are such that many feel “Jesus Sutra” a more accurate characterization of these texts. Me, among them.

Now the best single source about the religion and its texts for us today is Martin Palmer’s The Jesus Sutras: Rediscovering the Lost Scrolls of Daoist Christianity. It is a scholarly study. Although it is not without its critics, many of whom suggest he slants his translations in ways that are not fully warranted by the texts themselves. They argue Palmer makes the Buddhist and Daoist influences larger than is merited. That noted, me, I’m going for his version near whole hog. Okay, whole hog.

There are many significant features of this Luminous Religion. One that caught me quickly is the blending of Mary with Guanyin. Guanyin had already been transformed from an indigenous Chinese goddess into the Buddhist archetype of compassion. And here she finds herself reshaped once again with Mary, becoming a heartful image that many of us who’ve experienced both Buddhism and Christianity, including me, have long sense found for ourselves.

I’m also taken with the integration of Christian and Buddhist liturgical practices. And most important of all I’m just astonished at the “new” Christian texts of the Luminous Religion. Those Jesus Sutras promiscuously draw upon Buddhist and Daoist imagery and idioms. And with that transforming Christianity into something that I find very exciting and genuinely compelling.

The Luminous Religion was, as it were, innocent of Augustine’s terrible idea of original sin. Instead it fully embraced the loveliness of the world. And while celebrating the divine origins of their teacher, consistently emphasized his teachings as the truly important thing. They described the Luminous religion simply as a way of life.

Instead of sin and a judgment, they believed in karma and reincarnation. Now, for me and my naturalistic nature, in fact my Buddhism is hesitant about karma and rebirth in some literalist sense where our intentions and actions lead to some sort of post-mortem reanimation. However, even as classic Buddhist karma and rebirth are easily read in a naturalistic sense, it can just as easily be adapted in an engagement with the Luminous Religion.

My friend the independent scholar Adrian Worsfold summarizes the follows of this Way as “vegetarians, (who) promoted non-violence, charity, sexual equality, care for nature, and were (nearly uniquely in their world strongly) anti-slavery.” While the Luminouys Religion continues the trinitarian formula for baptism, it calls the spirit, “pure wind,” evoking the Chinese belief in Chi.

A Westerner can find a lot easily recognizable in the Jesus Sutras, although, as you can see, often with a twist. For instance, the Ten Commandments, now “covenants” blend Chinese sensibilities with recognizable biblical themes. But, there are teachings that more obviously echo the ancient wisdoms of Buddhism and Daoism, like the “Four Essential Laws of Christian Dharma.”

The first is no wanting. If your heart is obsessed with something, it manifests in all kinds of distorted ways. Distorted thoughts are the root of negative behavior…The second is no doing. Don’t put on a mask and pretend to be what you’re not…The effort needed to hold a direction is abandoned, and there is simply action and reaction. So, walk the Way of No Action. The third is no piousness. And what that meansis not wanting to have your good deeds broadcast to the nation. Do what’s right to bring people to the truthbut not for your own reputation’s sake. So, anyone who teaches the Triumphant Law, practicing the Way of Light to bring life to the truth, will know peace and happiness in company. But don’t talk it away. This is the Way of No Virtue. The fourth is no absolute. Don’t try to control everything. Don’t take sides in arguments about right and wrong. Treat everyone equally and live from day to day. It’s like a clear mirror that reflects everything anyway: Green or yellow or in any combination –It shows everything, as well as the smallest of details. What does the mirror do? It reflects without judgment.

The Luminous Religion calls us to a middle path, a Buddhist, Daoist, Christian middle way. It calls us into a deep investigation of our own lives, and it calls us into a community of mutual accountability.

Martin Palmer tells us, “The Jesus Sutras offer salvation from what we have made of ourselves – salvation from karma or (if you rather) from the burden of ‘original sin’ – because beneath the layers of our inadequate actions lies an original nature that is good. These spiritual, theological, psychological, philosophical, and ethical insights are in the Jesus Sutras, often beautifully and simply portrayed in accessible images, stories, and concepts.”

So fascinating, so wonderful. And so sad they were lost.

However, Palmer adds how, in fact, they only await our discovery, yours and mine. He invites us to embark out on our own Silk Road, our own journey of discovery. Palmer concludes his book with an observation. “After a thousand years, the Jesus Sutras have returned to us to shed light on the past, speak to our present, and, possibly, help shape our future.”

Here I find myself thinking of that “what if,” and realize in fact the door isn’t closed, rather it has been thrown wide open. We find something wondrous being presented. At least for those who have the eyes to see it, the ears to hear it.

We look at the world and ourselves and perhaps we want something different? We want to change this suffering world? Well, in some very important ways, we must start with ourselves. We need to let go of what we thought was so, what had to be so, and allow other possibilities to emerge.

And with that an invitation: Take that walk along the Silk Road for yourself. Read. Talk. Listen. Listen more than you talk. And most of all, pay attention. Then the way is revealed.

Amen.

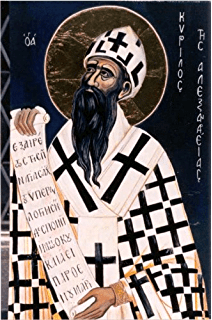

(A footnote about the image. It’s a 17th century Maria Kannon, a Dehua kiln statue of Buddhist Kannon used for Christian veneration in Japan, from the Nantoyōsō Collection.)