As we’re working on our Empty Moon website we quickly saw a need for a brief overview of the Soto school. The Wikipedia article on Soto is a flawed document, but nonetheless contains much useful information. We used it as a template, cutting anything that felt extraneous to that brief overview, while interpolating critical information that was missing. The text remains a bit rough, but seemed workable enough to share here. The text at the Empty Moon website will continue to be massaged for a while yet.

While not directly relevant to an introduction to Soto, this article also includes a few words about Empty Moon. Feel free to read or skip, as you find appropriate.

May this document be of assistance to anyone hoping to know more about this spiritual tradition both ancient and modern, holding profound insights and presenting disciplines that reveal the true nature of our hearts.

***

THE SOTO SCHOOL OF ZEN BUDDHISM: A BRIEF OVERVIEW

Sōtō Zen or the Sōtō school (曹洞宗 Sōtō-shū) is the largest of the three traditional schools of Zen in Japanese Buddhism (the others being Rinzai and Ōbaku). It is the Japanese line of the Chinese Cáodòng school, which was founded during the Tang dynasty by Dòngshān Liánjiè. It emphasizes the practice of Shikantaza.

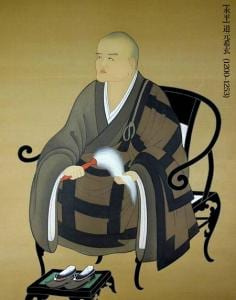

The Japanese school was imported in the 13th century by Dōgen Zenji, who studied Cáodòng Buddhism (Chinese: 曹洞宗; pinyin: Cáodòng Zōng) abroad in China. Dōgen is remembered today as the co-patriarch of Sōtō Zen in Japan along with Keizan Jōkin.

With about 14,000 temples, Sōtō is one of the largest Japanese Buddhist organizations. Sōtō Zen is now also popular in the West.

With about 14,000 temples, Sōtō is one of the largest Japanese Buddhist organizations. Sōtō Zen is now also popular in the West.

The Caodong-teachings were brought to Japan in 1227, when Dōgen returned to Japan after studying Ch’an in China and settled at Kennin-ji in Kyoto. Dōgen had received Dharma transmission from Tiantong Rujing at Qìngdé Temple, where Hongzhi Zhengjue once was abbot. Hongzhi’s writings on “silent illumination” had greatly influenced Dōgen’s own conception of shikantaza.

Dōgen also returned from China with various kōan anthologies and other texts, contributing to the transmission of the koan tradition to Japan.

In 1243 Dōgen founded Eihei-ji, one of the two head temples of Sōtō-shū today, choosing…” to create new monastic institutions based on the Chinese model and risk incurring the open hostility and opposition of the established schools.”

Dōgen was succeeded around 1236 by his disciple Koun Ejō (1198–1280)..

The second most important figure in Sōtō is Keizan. Keizan received ordination from Ejō when he was, twelve years old, shortly before Ejō’s death. When he was seventeen he went on a pilgrimage for three years throughout Japan. During this period, he studied Rinzai, Shingon and Tendai. After returning to Daijō-ji,

Keizan received dharma transmission from Gikai in 1294, and established Joman-ji. In 1303 Gikai appointed Keizan as abbot of Daijō-ji, a position he maintained until 1311. Under Keizan Soto Zen began to become popular.

In time the Sōtō school started to place a growing emphasis on textual authority. In 1615 the bakufu declared that “Eheiji’s standards (kakun) must be the rule for all Sōtō monks”. This came to mean all the writings of Dōgen became the normative source for the doctrines and organisation of the Sōtō school.

Dōgen scholarship came to a central position in the Sōtō sect with the writings of Menzan Zuihō (1683–1769), who wrote over a hundred works, including many commentaries on Dōgen’s major texts and analysis of his doctrines. Menzan promoted reforms of monastic regulations and practice, based on his reading of Dōgen.

Gentō Sokuchū (1729–1807), the 11th abbot of Eihei-ji, tried to “purify” the Sōtō school by functionally suppressing koan introspection as a Soto discipline. Prior to this kōan study was widely practiced in the Sōtō school.

During the Meiji period (1868–1912) Japan abandoned its feudal system and opened up to Western modernism. One of the significant characteristics of the Meiji reforms was the disestablishment of Buddhism. Its original intent was in fact the eradication of this ultimately foreign religion. In practice it led to some creative reforms. Specifically the Zen establishment sought to modernize Zen in accord with Western insights, while simultaneously maintaining a Japanese identity.

Among these reforms the legalization of clerical marriage is among the most distinctive. It brought together two streams unique to Japanese Buddhism. The first was the substitution of Bodhisattva vows for the Vinaya system used throughout most of the Buddhist world. The other was the temple system where after a period of training single monks would become incumbents of the thousands of temples throughout the Japanese islands.

Among these reforms the legalization of clerical marriage is among the most distinctive. It brought together two streams unique to Japanese Buddhism. The first was the substitution of Bodhisattva vows for the Vinaya system used throughout most of the Buddhist world. The other was the temple system where after a period of training single monks would become incumbents of the thousands of temples throughout the Japanese islands.

Records show these monks frequently having female companions. In the Meiji these two things, the ordinals had no specific language requiring celibacy, and on the ground a majority, likely a large majority were living in informal marriages, came to a head. That within five years of lifting of criminal sanction for marriage. fully eighty percent of Soto clergy were married shows this was a long over due reform.

That the terminology for these clerics remained monastic and that prominent clerics rarely appeared (or appear to this day) in public with their spouses and children has further complicated matters. Despite this there has been a trend toward seeing married clerics more as priests or ministers. This married clergy model has now been introduced to the West, where people are less comfortable with the “don’t ask, don’t tell” style of the Japanese culture, and now struggle to find appropriate accommodations for clerical marriage as a part of Zen in the West.

Going hand in hand with this non-monastic clerical leadership was the emergence of a philosophical perspective called “New Buddhism” (shin bukkyo��). This perspective, in significant part the product of Western encounter, was broadly modernist, holding up the values of lay life, with impulses supportive of democratic, rationalist, and social engagement.  It can be argued everyone who brought Soto Zen to the West was influenced by this New Buddhist perspective, at least in some degree. And practically, it brought a form of Soto Zen that could be recognized in many ways by Westerners.

It can be argued everyone who brought Soto Zen to the West was influenced by this New Buddhist perspective, at least in some degree. And practically, it brought a form of Soto Zen that could be recognized in many ways by Westerners.

SOTO COMES WEST

In 1922 the Reverend Hosen Isobe established the first Soto temple on the mainland of the United States, in Los Angeles. Its intent was to serve the Japanese and Japanese American community. Shortly before the Second World War the Reverend Soyu Matsuoka arrived from Japan and began to work with European and African American converts.

But it was with Shunryū Suzuki that Soto Zen began a significant mission to the American heart. Suzuki studied at Komazawa University, the Sōtō Zen university in Tokyo.

In 1959 Suzuki arrived in California as minister of Soko-ji, at that time the sole Sōtō temple in San Francisco. Suzuki’s teaching of Shikantaza and Zen practice and opens to converts, led to the formation of the San Francisco Zen Center, one of the largest and most successful Zen organizations in the West.

The training monastery of the San Francisco Zen center, at Tassajara Hot Springs in central California, was the first Buddhist Monastery to be established outside Asia. Today SFZC includes Tassajara Monastery, Green Gulch Farm, and City Center. Various Zen Centers around the U.S. are part of the dharma lineage of San Francisco Zen Center and maintain close organizational ties with it.

Suzuki Roshi’s book Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind has become a classic in western Zen culture.

Suzuki’s assistant Dainin Katagiri was invited to come to Minneapolis, Minnesota, where he moved in 1972 after Suzuki’s death. Katagiri and his students built four Sōtō Zen centers within Minneapolis–Saint Paul. Another of Suzuki’s assistants, Kobun Chino Otogawa also become influential in establishing Soto in the West.

It was here in the West that Soto also began to reclaim koan introspection. The lineage, started with Daiun Sogaku Harada, who also has a line that passes more continuously within the Soto school, and through him to Hakuun Yasutani, includes Taizan Maezumi, who gave dharma transmission to various American students, among them Tetsugen Bernard Glassman, Charlotte Joko Beck and John Daido Loori.

The lay organization Sanbo Kyodan, and through that lineage in an independent organization, Robert Aitken, who had several important dharma successors, including John Tarrant. cemented the place of a Soto reformed koan curriculum in Western Zen practice.

The Antaiji-based lineage of Kōdō Sawaki with its emphasis on shikantaza over all other practices, is also widespread. Sawaki’s student and successor as abbot Kōshō Uchiyama was the teacher of Shōhaku Okumura who established the Sanshin Zen Community in Bloomington, Indiana. Rempo Niwa was associated with Antai-ji, and his student Gudō Wafu Nishijima was Brad Warner‘s teacher.

Houn Jiyu-Kennett (1924-1996) was the first western female Soto Zen priest. She converted to Buddhism in the early 1950s, and studied in Sojiji, Japan, from 1962 to 1963. Formally, Keido Chisan Koho Zenji was her teacher, but practically, one of Koho Zenji’s senior officers, Suigan Yogo roshi, was her main instructor.[47] She became Oshō, i.e. “priest” or “teacher,” in 1963. In 1969 she returned to the west, founding Shasta Abbey in 1970.

In 1996 the majority of North American Sōtō priests joined together to form the Soto Zen Buddhist Association. While institutionally independent of the Japanese Sōtōshū, the Sōtō Zen Buddhist Association works closely with it.

EMPTY MOON

Our founding teacher and priest is James Myoun Ford. He was originally ordained a priest by Jiyu Kennett, and received dharma transmission from her in 1971. He also completed the formal Soto reformed koan curriculum developed by Daiun Sogaku Harada and received Inka shomei from Dr John Tarrant.

A long time member of the Soto Zen Buddhist Association, Ford Roshi participated in the first Dharma heritage ceremony in 2004. It was meant to be a recognition of seniority in Western Soto Zen roughly equivalent to the Japanese zuise ceremony. In 2012 he was Doshi or chief celebrant at the fifth Dharma heritage ceremony. Ford later served on its board for a three year term.

The Empty Moon is dedicated to the project of awakening. It seeks to preserve the traditions of Soto Zen cautiously adapted to the needs of our time and place, while also transmitting the reformed koan curriculum, It also stands for a radical equality between priest and lay practitioners, the total equality of genders, and the development of a rigorous but pragmatic formation process for priest practitioners.

***

For a brief summation of the core teachings of the Soto school, we recommend the Shushogi, the “Meaning of Practice & Verification,” compiled out of Eihei Dogen’s teachings by a team of scholars led by Ouchi Seiran.

For descriptions of Zen meditation we recommend this brief overview, as well as Eihei Dogen’s Fukanzazengi, Keizan Jokin’s Zazen Yojinki, and this introduction to koan introspection within the Soto reformed style.

For further reading about the Empty Moon project, here are some links:

Awakening and Zen

My Three Years on the Soto Zen Buddhist Association Board

Zen Practice for Everyone