WALKING THROUGH THE VALLEY OF THE SHADOW

Reflecting on the 23rd Psalm, Buddhism, Nondual Christianity, Broken Hearts, and a way of Intimacy

James Ishmael Ford

I think it was two years ago. Jan & I went to the Bowers Museum in Santa Ana to see the special exhibition of Frank Hurley’s amazing photographs of Ernest Shackleton’s catastrophic 1914 Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition. Hurley was an amazing photographer, later famous for his work accompanying Australian forces during the Great War.

I came away with several images burned into my heart, as well as thoughts about a range of issues. One of these thoughts had nothing directly to do with the photographs. But in this time we’re all caught up in, in this time of plague and looming disaster, it may be something that can be helpful.

Actually, it was a display of Shackleton’s Bible that most riveted my attention at the time. And it is that Bible that I find myself thinking about. The caption for the Bible, explained that it had been presented to Shackleton by King Edward VII’s wife, Queen Alexandra. Interesting enough. But, there’s more to the story.

At the direst of moments, facing the likelihood of death and the thinnest chance of survival, Shackleton tore out three pages and then discarded the book. He would carry those pages with him as he led an 800 mile journey in an open life-boat. The majority of the twenty-eight souls who made up the crew would wait on a tiny island until he was able to return and rescue everybody. A remarkable thing. A story of heroism. The Bible itself was actually salvaged by a crew member who carried it through that harrowing they all endured.

Both Shackleton’s choice of those three pages and the crew member’s choice to include the whole book in that same horrific moment touched me. I was impressed at how the crew member, who had to make a decision about what to carry. But, what caught me most were those three pages.

One was the title page which had been inscribed by the Queen. Another was a page including Job 38:29-30. “Out of whose womb came the ice? and the hoary frost of heaven, who hath/gendered it?/The waters are hid as with a stone, and the face of the deep is frozen.” A naked acknowledgement of powerlessness in the face of terrible and overwhelming forces. I very much get that. Maybe we’re all getting a taste of that.

The third was the page containing the 23rd Psalm. The King James version. Of course. And for the majority of us even yet “the” version.

The Lord is my shepherd; I shall not want.

He taketh me to lie down in green pastures: he leads me beside the still waters.

He restoreth my soul: he leads me in the paths of righteousness for his name’s sake.

Yea, though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death,

I will fear no evil: for thou art

with me; thy rod and thy staff they comfort me.

Thou prepares a table before me in the presence of mine enemies:

thou anointest my head with oil; my cup runneth over.

Surely goodness and mercy shall follow me all the days of my life:

and I will dwell in the house of the Lord forever.

Now the page with the inscription meant nothing in particular to me. I mean royals make for good television, I guess, and in England seem to be good business for tabloid newspapers. But at the end of the day, so what? I grant it might have a more mystical meaning for those people at that time. Still, for them, not for me.

But, the other parts, they were different. They speak to larger currents within our human hearts. The Job passage was an acknowledgement of our powerlessness in the face of the majesty, sometimes lovely, often terrible, of what is. And. That 23rd psalm. Out of the whole of the scriptures that he would pick that one thing at hard times, I get that.

I am not a Christian, certainly, not by normative standards. But I was raised Christian, and it is the dominant spiritual expression within our culture. The Bible and its stories, especially in the King James translation is part of the air we breathe. And the 23rd Pslam.

I immediately knew what the 23rd Psalm was, and even was able to recite a good part of it from memory. Me, someone with virtually no memory to speak of. Never had. I probably know by heart a grand total of five or ten pages of text from all that I’ve read over the years. I know a couple of verses of the “Battle Hymn of the Republic,” and I can sing “Row, Row, Row Your Boat.” Maybe there’s another song I can be prompted to sing. But as I typed these words, I couldn’t think of what it might be.

There’s a tiny bit more. As a Zen practitioner, I need prompting, but I do have the Heart Sutra by heart, as well as a handful of other texts, most notably the meal chants. And one version of the verse of the kesa.

Vast is the robe of liberation,

A formless field of benefaction.

I wear the Tathagata’s teachings,

Saving all the many beings.

As a Zen teacher I’m often asked, “how do you meditate with a koan?” To which I have to respond, “I have no idea.” I have no idea because during the years when I was formally engaging the practice, the convention is that you have to memorize the case and present it to your spiritual director, who then digs into the critical points. And, for most of those years I was mainly busy trying to memorize the case just well enough to present it to the teacher. That was my “working” with the koan. Everything beyond took place in the interview room.

Today, after having walked through the practice, having memorized much of the collection, hundreds and hundreds of cases, today I can recite exactly one:

A student of the way came to Zhaozhou and asked,” Does a dog have Buddha nature?”

Zhaozhou replied, “No.”

Usually that “no” is rendered as “Mu.”

So, that I can recite it, most, imperfectly, it’s always imperfectly, clearly the 23rd Psalm has a special place in my heart.

Actually, I am aware of two Zen-inspired translations of the 23rd Psalm.

One is from the old Zen hand and poet Stephen Mitchell:

The Lord is my shepherd:

I have everything that I need.

He makes me lie down in green pastures;

He leads me beside the still waters;

He refreshes my soul.

He guides me on the paths of righteousness,

So that I may serve him with love. Though I walk through the darkest valley

Or stand in the shadow of death, I am not afraid,

For you are always with me. You spread a full tables before me, Even in times of great pain; You feast me with your abundance

And honor me like a king, Anointing my head with sweet oil, Filling my cup to the brim.

Surely goodness and mercy will follow me All the days of my life,

And I will live in God’s radiance Forever and ever.

The other is from the Zen teacher and poet Norman Fischer:

You are my shepherd, I am content

You lead me to rest in the sweet grasses

To lie down by the quiet waters

And I am refreshed.

You lead me down the right path

The path that unwinds in the pattern of your name.

And even if I walk through the valley of the shadow of death I will not fear

For you are with me

Comforting me with your rod and your staff

Showing me each step.

You prepare a table for me

In the midst of my adversity And moisten my head with oil.

Surely my cup is overflowing

And goodness and kindness will follow me All the days of my life

And in the long days beyond

I will always live within your house.

While I find both helpful, Roshi Fischer’s version is my favorite. With each version there is that subtle turn into addressing the ultimate which I find brings the visceral truth of the song right to the fore. Intimacy. It’s all about intimacy.

As I contemplated these things I began to wonder if other people of Zen have a relationship with the psalm. And, so I googled it. Using the search terms “Zen” and “Psalm 23.” I found a lot. Mostly unhelpful. But, some, very much so.

The wonderful householder Zen teacher Susan Moon writes about developing her own practices. “Prayer was something I missed in Zen practice as I knew it, so I imported it from Christianity and other Buddhist traditions. I prayed to Tara, Tibetan goddess of compassion, to fly down from the sky, all green and shining, into my heart. I prayed to Prajna Paramita, the mother of all Buddhas, who ‘brings light so that all fear and distress may be forsaken, and disperses the gloom and darkness of delusion.’ These words (from the ancient Prajnaparamitta sutra) reminded me of the 23rd Psalm: ‘Yea, though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil, for Thou art with me.’ I said this too.”

And that opened another point for me. I’ve been thinking about prayer a lot. As someone who does not believe in a deity in the sense of a being with a human-like consciousness whom I can petition to get out of one jam or another, I have to ask myself what prayer might mean.

In my wanderings around the web I stumbled upon a memoir that touched on that very question. “The Tender Bud: A Physician’s Journey Through Breast Cancer” by the pseudonymous Madeleine Meldin. As it ha has a page that has those search terms “Zen” and “Psalm 23” both included.

First, she cited a “Zen anecdote.” She gives it a wonderful interpretation. “Meaning is there where you are fully where you are.” While I don’t know the source, the teaching is true. And then with that resting in our hearts, Dr Meldin tells us:

“In being born and in dying we are alone. From now on, I began to understand, I had to live my everyday life with its every delightful and annoying detail, while trying to advance, in darkness and in light, on the road to uncompromising meaning.

“I also became a pilgrim in the many corridors of the hospital ward. The doctors recommended that I walk and exercise my arm to help the recovery. It was the oncology war. Looking at all of us, some young people, half eaten by cancer, some courageous, terminally ill old gentlemen, and others, I recalled the 23rd psalm: ‘The Lord is my shepherd… Even though I walk in the valley of the dead I shall not fear.‘”

She then adds, “But I felt fear, the fear of death, of protracted illness, of losing mastery over my life.” I found that very important. No fear. And, of course, fear. A pointer for us, today, here, now? Perhaps.

Continuing my google search I found a former Catholic priest and psychologist, Ron Roth commenting on the 23rd Psalm, “The Zen master Rinzai, who lived in China in the ninth century, would hold up a finger to his students and ask, ‘What, in this moment, is lacking?’ Perhaps his greatest interpreter, the 18th-century Japanese Zen master Hakuin, wrote, ‘At this moment, what more need we seek?’”

At this moment. What more do we need?

Here a lot of things began to come together.

So, if it isn’t petition, what is prayer? I think Dr Roth gives as good a pointer as we might want. If there is no place to go, if this place, the place where many of us are under stay at home orders, and all of us with restricted movements, in this place with disease and economic catastrophe hanging all around us. This moment.

What questions should we be asking? What about our own heart? My heart? Your heart? What about fear and fearlessness? As we look what do we find?

Here is the secret place of Leonard Cohen’s hymns Hallelujah and Anthem. Here is the meeting of heaven and earth. Here in the broken place, in the valley of the shadow of death; this is where we meet the divine.

And here is where I find the meaning of prayer. It is my heart reaching out to the holy. And, when I am lucky, when the divine touches me within that holiness. Intimacy. Intimate.

Divine. An interesting word. The holy. The sacred. God. The intimate. The language of transformation. Within the interesting times we are called to live in, I see Buddhism in dialogue with the traditions of the West, ranging from psychology to Judaism and Christianity.

As a birthright Christian I am especially interested in the rise of a nondual Christianity. There appear to be corollaries in Judaism, as well. Looking at those old stories and traditions without assuming dualism, an ultimate gap between the holy, God, and this world, and specifically, us. And it is a two-way street. There is no absolute truth, we all get a little angle on it, it is always, always through a glass darkly. And with that and within these encounters, Buddhism is currently being enriched, as well.

In the terms of the Heart Sutra, one of those few texts I have stored in my memory, form, this body, this world, is empty, is endless potential, is divine. And the divine, God, the holy, the boundless, is nothing other than our lives, lived.

Here with new ears I can hear the psalm. I can hear the sorrow and the fear of life as it is lived, particularly now in this time of plague. And, and this is so important: I can hear a secret joy, and a true comfort. While we, you and I are as passing as a child’s breath, we are also the stuff of the divine. We are God’s eyes, we are God’s heart, and we are God’s hands.

And our comfort, and our joy, and our lives are contained within the warm embrace of the holy. Along with, I hope, the hard realities. Within the mysteries of not one, not two, we are all of us responsible.

And. But. Also. Importantly, importantly. In moments like these, how can we not look to the deep? How can we not allow the sadness and the fear their place? And, how can we not open ourselves to the embrace of the holy?

Even as we walk through the valley of the shadow.

A grace. For many of us a broken grace. Well. Maybe for all of us.

But a grace, nonetheless.

Found anytime we open our hearts fully…

Amen.

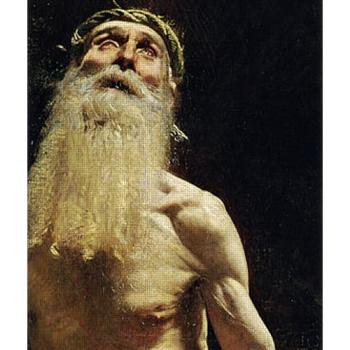

The illustration is by the artist Yuan Qinlu