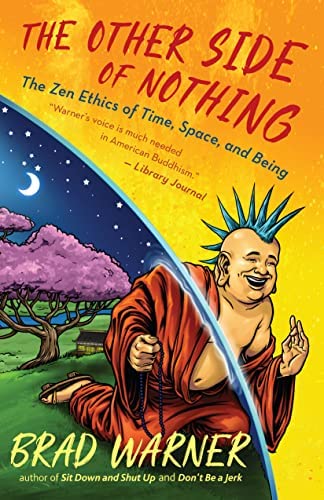

Other Side of Nothing: The Zen Ethics of Time, Space, and Being

Brad Warner

New World Library, Novato, 2022

A Review

James Ishmael Ford

I was offered a copy of Brad Warner’s new book, the Other Side of Nothing in exchange for a review. I said sure.

Now the pile of what I must be reading has gotten so high I’m in danger of the pile collapsing with who knows what possible devastation following. As it turns out it’s also a larger book than anything else he’s written, at least as I recall. Finally, accepting that I wanted to read it, but had limited time to devote to it, I jumped in and read it in one sitting. I feel a bit too fast. It deserved better. But, I believe I have it well enough down to give an honest and helpful review.

The opening sentence of the book is “You are not reading this book.” I thought, okay. So? And? Well, the “and” of it was to explain to the reader that “There is no ‘you.’” Rather, the whole idea of a self is a fiction. Brad defines this perspective as nondualism. Actually, I find such a bald statement an un-nuanced version of nonduality. But okay. I’ve read several of Brad Warner’s books, he often likes to begin with something startling, and I’ve generally found what he has to say after that helpful. So, I continued.

A couple pages further in he wants us to know “Zen Buddhism is not a religion.” He went on to say how for the most part Zen Buddhists don’t “like to call themselves ‘Zen Buddhists.’” The first assertion is a view, and one held by many. And it’s a view with which I have some serious affinities. But, a truth of the matter is, there are very compelling reasons to say Zen Buddhism is very much a religion. In fact I think it fair to say most people with an informed view of comparative religious studies would categorize Zen Buddhism very much as a religion. And I’m confident his second statement is simply factually incorrect beyond a caveat for cultural linguistic usage. A subset of Western Zen Buddhists might resist the designation. But not most.

At this point if it weren’t a book by Brad Warner, I’d put it down.

However, I persisted.

He goes on to explain the original intent of the book is an exploration of Zen Buddhist ethics. A rich subject. There are only a small handful of such investigation available. As a small aside in my view the earliest English language effort is probably still the best, Robert Aitken’s Mind of Clover: Essays in Zen Buddhist Ethics. Check it out.

But, Warner says he quickly found that an exploration of Zen and Buddhism’s understanding of the structures of reality is critical if we want to understand Zen’s views about ethics. Here, I found myself agreeing and, rather more importantly, interested in his take on the matter. I find I learn things reading Warner.

He quickly outlines a description of Zen Buddhism that a scholar would probably call “modernist.” It resonates with my views. He also offered his assertion:

“Zen Buddhism is not a set of beliefs and dogmas. Rather, it’s a way to learn to clearly see what reality actually is, beyond all dogmas and beliefs.”

Of course there are lots of beliefs and dogmas in Zen and in Buddhism. And, I agree with Warner, Zen Buddhism is also a way to learn how to clearly see what reality actually is. I think noting it is a messy project might have been more helpful. Certainly it would be more accurate. One might say in spite of Zen’s beliefs and dogmas there is a way into genuine depth.

Beliefs and dogmas I find are especially dangerous to someone seeking to encounter for oneself what actually is. Ideas about the deep are quite seductive, especially when they’re most accurate. The temptation with the best of beliefs and dogmas is to find ourselves settling for someone else’s understanding. People do it all the time, sometimes with wildly unlikely beliefs, sometimes with subtle and profound beliefs. Zen people, well, you bet they’re not excluded from missing the invitation because their statements of belief and their dogmas cut closer to true than one often finds in religions.

But he doesn’t spend a whole lot of time there. Instead he quickly moves to the point.

Here Warner offers some insights from the Japanese missionary Shohaku Okumura, who uses a lovely analogy of a music performance to point to how we exist within that real. For me a critical sentence and worthy for anyone hoping for a genuine pointer on their own way into the deep goes, “We cannot say oneness and multiplicity are different and we cannot say they are the same.”

This is the mess of the real. Warner is right you don’t exist. Nor do I. And, at the same time, of course we do, you and I. What is missing in the bald assertion is the contingency of our existence. In the Zen text the Jewel Mirror Samadhi we are told “you are not it, but in truth it is you.” That. I really appreciated Warner’s unpacking of nonduality from a Zen perspective. He especially knows his Dogen.

He then elided into a citation of the modern Advatia Vedanta Hindu teacher Nisargadatta Maharaj, introducing the word illusion. In my Zen training the word illusion was usually avoided. It’s an important Hindu term, but Zen teachers, in my experience, resist it as too easy a place to rest, and a way to miss what we really are. Something a bit messier than illusion with an implied real opposed to the illusion.

It also implied that as we proceeded, we would not be limited to a single angle on the mystery of the real. That we would step away from the beliefs and dogmas of Zen in this investigation. Certainly works for me. If we want to avoid the traps of beliefs and dogmas on the way of intimacy a little comparative mysticism can be enormously helpful.

And. One of the things I like about Brad Warner, which can be missed with his penchant for categorical statements about what Zen Buddhism is. And that’s his persistent assertion he makes mistakes, he misses things, he is learning. Me too. Along side the bravado is a real person of the way. So, I continued on to learn from him in his new book. With as we all do when reading anything worth reading engaging in a dialogue.

The book sets the stage a bit more fully with a brief account of how he came to be the person writing this book. I’ve read versions of this before, and this is Brad at his most mature confessional style. It was inviting and echoes much of the attraction many of us who like Brad Warner’s work over the years.

Then he opens the door toward the Advaita, or as he correctly say neo-Advaita that will be part of the dialogue of the book. He also summarized the teachings of his primary teacher Gudo Nishijima, which is critical for anyone trying to understand Warner’s school of Zen. There are several, and as noted he has a tendency to present his view as normative.

Warner then outlines the Eightfold Path teaching with constant reference to personal behavior, to our individual ethics. It’s good. At this point in my life old territory. But, he opened angles and it was worth the read.

It’s critical for anyone hoping to understand Zen’s take on the nondual to have some sense of the Heart Sutra, and Warner does a good job welcoming us into that ancient text. He also offers one of my favorite chapters in the book, a reflection on makyo, which was published in Tricycle.

With this he turns to the precepts as understood in Japanese Zen.

But as he says it was his original intention to write about ethics, and after giving the precepts their due, he turns back to that world view thing, the idea of nonduality, and its invitations. Warner’s foundation is Dogen’s Zen. And a very good foundation it is. He has spent a great deal of his life studying and reflecting on those teachings as pointers in his own practice and his developed view of how things are.

I really liked that. It’s informed, it’s well written, it points to what I believe in my bones to be true. Presented from different enough of an angle for me to stretch and learn. I’m grateful.

He then turns to neo-Vedanta. An area I know little about, but which has long intrigued me. In my own quest for challenges, corrections, and invitations into the deeper aspects of Zen, I’ve personally turned mostly to Christian mystics. (As a small aside there’s another book with nearly the same title the Other Side of Emptiness that might be worth a read for anyone interested in what one might find out of nonduality when approached from the Christian mystical perspective.) Here I see what wealth there is to be found in India’s great response to Buddhism.

Somewhere about sixty percent of the way maybe a bit more through he offers an extensive quote from the old Anglo-American trickster teacher Alan Watts. In that kind of wonderful coincidence some make meaningful, I’ve been thinking a lot of Watt’s line about the universe being God playing peek-a-boo with itself. I’d been trying to recall the exact line, when I found it here in Warner’s book. Turns out the quote comes from the Book on the Taboo against Knowing Who You Are, which I read maybe fifty years ago, fifty years and change in all likelihood. As it turns out the image was hide and seek rather than peek-a-boo.

“…when God plays hide and pretends that he is you and I, he does it so well that it takes him a long time to remember where and how he hid himself…”

For Watts and Warner and, well, me, this is not the God of Abraham. At least not the God of Abraham most people think of when they say the word. The path of peek-a-boo, of hide and seek, for Watt’s noticing this is a call into sacred play. I think this is much of how Brad Warner sees the intimate matter, himself. Not normative Zen Buddhism, but authentic. As I said I’ve been thinking about this perspective a lot of late, myself. It has a ring of truth to it in my life. Although this God absolutely should not be taken as kittens and puppies. Recalling Arjuna’s confrontation with the destroyer of universes is important. Or, maybe Job’s.

Brad Warner’s concluding paragraph is called the Human Project. I take it as his best attempt at describing where this mysterious path we share in part has taken him.

My take on this book? Brad Warner is a serious life long practitioner of the Zen way. And over the many years he has come to something attractive, and I believe useful. As to this book? As a straight-forward introduction to Zen ethics I think there are better books. As a straight-forward exploration of nondualism, I think one is better off with Nonduality: In Buddhism and Beyond by David Loy.

I think he misses the part about social ill pretty much completely. A shadow of the modernist approach to Zen is a kind of reductionism. It actually can go in two ways. One is to forget it is a spiritual project. The other is to forget it isn’t really a self-improvement project, either. Brad’s Zen is ultimately, at least as I find he presents it, a profoundly personal project.

I noticed this especially in his understanding of karma. It’s all personal. Part of the reason it is abhorrent to blame the victim as we see in a reductionist and totally personal understanding of causality, is that cause and effect does not stop at one’s skin. Cause and effect is vast, and we have agency over only a part of the part we usefully call “me.” The thing Brad noted at the very beginning doesn’t really exist.

It’s messy. And Warner is certainly correct when he wrote of the great mess,

“You can’t make fix the economy, heal the natural environment, undo centuries of human abuse and neglect….But you can make a little difference. So make a little difference!“

I largely agree. And I think the mess of our awakening into our radical interdependence calls for at least a bit more attention to what that little difference might look like for someone walking the Zen way. Especially in our time and place where most of us reading Warner’s book or this review live in more or less democratic cultures with, in my view, an obligation of citizenship being involvement.

Finding the path that embraces the inward look is critical. But in my experience it also needs that hand reaching out. These days serious reflections on where the balance is are important. In my view.

I find the book a bit of a hot mess. It might have best been two books. Although as I noticed it’s more than helpful that Zen’s nonduality and the precepts are seen as co-arising. And he very much attends to the personal aspects of this co-arising. Which I found helpful for me. And thought will be helpful for others.

I do wish the book had an index.

What The Other Side of Nothing Is, in my view, is an honest and soul-searching personal confession of Zen Buddhism as an expression of the human encounter called nonduality, with some good words on practice, and some helpful reflections on rubber hitting the road stuff as regards individual behaviors in this messy world.

It’s a good book.

(Oh, and Brad. Regarding your conclusion. Right back atcha!)

I recommend it.