HELL IN THE CHRISTIAN TRADITION

Some Notes for a Larger Reflection on Universalism

After creating the Heavens and the Earth, God created a garden east of Eden and populated it with everything that is good to eat and is pleasant to see. The Divine also planted the tree of everlasting life as well as the tree of the knowledge of good and evil.

God then created the man and the woman. And the Divine said to them they may eat of all the fruit in the garden, except for the fruit of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil. If you do, the people were told, you will die.

Then the serpent said to the man and woman, eat that fruit, and you will become as gods. And they did. Instantly they knew they were naked. And they covered their shame.

When God returned to the garden and saw their shame, the Divine cursed the serpent, and the man, and the woman. He said the snake will be hated, and the man and the woman will labor, and it will be hard, and they will sweat and strain. And then in time they will die, dust returning to dust.

Then before they could eat of the fruit of the tree of life, God cast them out of the garden. And the Divine set an angelic being with a flaming sword to bar anyone from the garden and the tree of life.

Retold from the creation myths of the Abrahamic tradition in Genesis 2-3

A constant of the human condition is a pervasive intuition of wrongness. It is a sense there is something sour in everything no matter how sweet it seems. It hangs in the air. Something is off. It whispers in the night. Something is profoundly wrong. Each of the world’s religions has looked at this intuition as old as our humanity. And each religion has suggested what precisely that problem is. And then has offered a way to remedy it.

In his study God is Not One, Stephen Prothero offered some single word summaries of how this deep human intuition of a pervading problem could be understood, and with that the fix. So, for Buddhism, that dis-ease is called suffering, and the solution is awakening. In Confucianism, the problem is chaos, and the solution is order. In the Abrahamic traditions, for Judaism the problem is exile, and the solution is return. For Islam the problem is pride, and the solution is submission. And for Christianity the problem is sin, and the solution is salvation.

Both Judaism and Islam retain that ancient creation story of Adam and Eve and their exile. But in addressing the mess of human hurt, Islam calls for a humble bow before the majesty of the Divine and aligning one’s actions with the God’s will. While Judaism takes that hint of exile, and finds it developed in another story, the Egyptian captivity. And exile is resolved in the return to the promised land.

In Christianity that sin attributed to Adam and Eve is the problem. With sin comes chaos, corruption, all sorts of evil. And ultimately it brings death. There are any number of ways this could be understood, but as Christianity evolved two became normative.

For the Orthodox family the Ancestral sin represents the common human condition, our fragility, and our mortality. And in this understanding the exile from the garden is so that humanity can find a way back into harmony and the ways of reclaiming the divine as a birthright. But in the West, at least from Augustine of Hippo, it becomes Original sin. Because of Adam and Eve and their sin, we have inherited death. The difference being with an understanding of Ancestral sin the focus is on our mortality and God’s love. And with Original sin the focus is on human guilt and Divine wrath.

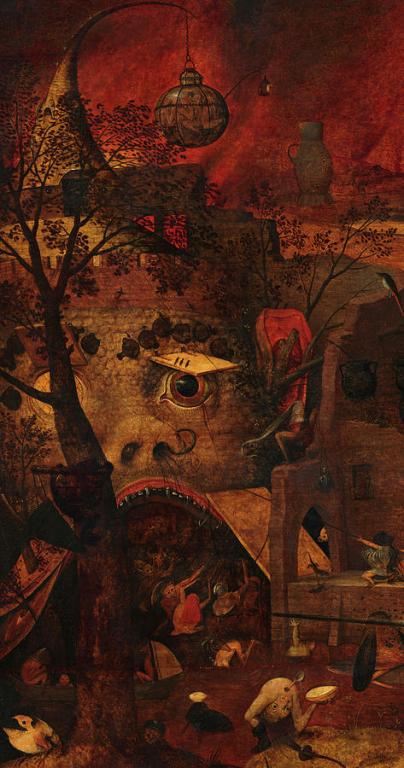

And with that Hell.

There is a story told about the great William Ellery Channing, one of the founders of the American Unitarian movement in the early Nineteenth century. As historian David Robinson recounts it:

“Taken one day by his father to hear a ‘famous preacher,’ he was introduced to the Calvinist vision of human depravity, of lost souls in a dark universe, in desperate need of ‘sovereign grace.’ The sombre terror of the sermon struck the sensitive boy deeply, and when his father later pronounced it ‘sound doctrine,’ young Channing was crushed: ‘It is all true then.’ But as the boy’s anguish grew during the silent drive home, he was jarred when his father began to whistle. And when his father reached home and proceeded calmly to read his newspaper, the boy realized something: ‘No! his father did not believe it; people did not believe it! It was not true!’”

Somehow along the way normative Christianity, especially in the West has turned on the idea of a sin so terrible that it demands eternal punishment. People of good will and integrity have looked at it and have struggled. If it’s true. As horrific as that would be, then we need to deal with it.

However, an honest look at Hell in the Western tradition shows that it has a history. It evolves, and it takes several shapes. The idea of a conscious eternal torment as the fate of the vastly greater part of humanity is not a necessary conclusion to the Christian intuition of sin and salvation. I suggest that young Channing’s recoil is appropriate.

And that those who find resonances with the message of Jesus, including the story of him as a link in the reconciliation of humanity and the Divine, that Hell as some eternal punishment is in no way necessary. And, actually, as the Orthodox theologian David Bently Hart suggests, this teaching of an eternal punishment is “manifestly absurd,” “abominable,” “loathsome and degrading,” “perverse,” “inexcusably cruel,” and “morally corrupt.” To partially cite him on the subject.

As an aside I am a bit surprised at how offended some people are at Dr Hart’s strong statements about the idea of Hell. Considering, well, eternal conscious torment. And attributing it as the God of love’s will.

Most to the point, if not a given for the Christian tradition demanding some terrible redeeming sacrifice, how does Hell arise in the Western tradition?

In early Judaism, as in most other Ancient Near Eastern religions, the rewards of the righteous are for a long life in this body. And rewards and punishments for goodness and wickedness are found in this life. While the contradictions are noted, Job offering the classic response to a facile belief that wealth and health are signs of righteousness.

In the earliest strata of the Hebrew scriptures, the soul, that animating part of the human, survives physical death, but as little more than a shadow that’s transported to sheol. sheol looks very similar to the ancient Greek hades.

There is no certain etymology for the word, but possibly sheol alludes to the grave, itself. In Job and Lamentations, sheol is a “dark place.” In Numbers and Amos, it under the earth. In 2 Samuel and, again Job, it is a place of sleep. Job speaks of dust and worms, while the Psalms describe silence.

For much of the Hebrew Scriptures it appears sheol is the common destination of all people. Although some scholars note the righteous are less commonly described as going to sheol. Often more positive images are used. In Genesis the righteous are “gathered to the ancestors,” and in 1 Kings, they “sleep with their fathers.” Of course, these terms can mean the same thing, that common grave.

I think it fair to see the Book of Job the Ancient Hebrew response to the conundrum of life and death, where it all seems to even out, as we read in Ecclesiastes 9:2:

“(S)ince one fate comes to all, to the righteous and the wicked, to the good and the evil, to the clean and the unclean, to him who sacrifices and him who does not sacrifice. As is the good man, so is the sinner; and he who swears is as he who shuns an oath.”

And that fate is the grave. Sheol. Dust to dust.

Job engages the conundrum creatively. I love that no one knows the actual origins of the earliest strata. It’s generally attributed to the common spiritual lore of the Ancient Near East. What is fairly clear is that none of the names are traditionally Jewish. At least up until that time. The earliest parts of the text are the prose forward and afterward, which disappear into the mists at or before the sixth century before our common era.

The powerful poetic part that occupies the middle of the book we know was composed, almost certainly in parts from the sixth century before and on for maybe two centuries more. The final text is an ambiguous testimony to one of two understandings. Perhaps a bowing before the power and majesty of something beyond our ken. Or, maybe it’s an invitation into a direct encounter with that unknowable majesty. A presence to what is.

However, the path toward the Christian worldview continues.

In the Intertestamental period, which includes the Hellenistic occupation, an interest in rewards and punishments beyond the grave continue to evolve in Jewish thought. Mostly the wicked are annihilated. However, in the book of Daniel, the wicked are punished postmortem. Similarly in the Greek world Hades moves from our common fate to two places. Elysium for the righteous and Tartarus for the wicked.

There are various views about how punishment of the wicked dead arises. It happens in Egypt. And there’s no doubt that Egypt looms large in the Jewish imagination. The great driving myth of the Jewish tradition of movement from slavery to freedom turns on a captivity in Egypt. Direct and indirect influences seem inescapable.

Similarly, there’s Zoroastrianism. The tradition is deeply dualistic with a good God and an evil one locked in a struggle. And in the tradition with death the good go to the House of Welcome, with many rewards, while the wicked go to the House of the Lie, which is dark and where all the food is rotten.

It’s a common trope that the idea of angels passed into Judaism from Zoroastrianism. It’s not a great leap to assume other influences, as well. Some scholars see Zoroastrian influences in Second Isaiah. The most obvious seems to be the rise of dualism within later Judaism. But it’s all inferential.

Another possible influence comes from the Greeks. When Alexander conquered all of the Near East, that included the obscure corner of the empire we now think of as Israel and Palestine. With his death the Jewish homeland was in a liminal place between two Hellenistic kingdoms.

During most of the third century before the common era Judea was ruled by the Egyptian based Ptolomies. For the balance of the second century, again before the common era, Judea was ruled by the Seleucids. A terrible time filled with dream and rebellion. And among other things with thoughts of rewards and punishments. And then a brief successful rebellion followed by a fundamentalist kingdom, the Romans marched in.

A very good argument is that among the gifts the Greeks brought with them was the legend of hell found in Plato’s Republic. Whatever. Wherever. By the Intertestmental times two things became features of the spiritual landscape in Judea. Apocalyptic endings. And judgements. Dreams of revolution, dreams of a prophet, a messiah to lead the people to throw off the shackles of empire.

Whatever else Jesus was, he was an apocalyptic preacher. He spoke of the rich and the poor, he spoke of oppressors and the oppressed, and he pronounced a world that was partially in the immediate future and partially here and now.

In his sermons captured in the Synoptic gospels Jesus used the word gehenna eleven times. It’s used one other time in the New Testament, as well, in the epistle of James. It refers to a physical place outside of Jerusalem. There’s a prevailing myth it was the city’s dump, but that’s a late medieval interpretation. It was a place outside the original gates of the city, the valley of Hinnom, and was associated with ancient sacrifices. The word gehenna was used in Jesus’ time to convey shame, and with that regret. The Greek Hades appears ten times in the New Testament. It’s used as a synonym for sheol. The Greek tartarus appears once in First Timothy, as well.

What literal and what metaphorical understandings in that day are pretty much lost to us. We have ideas. Some pretty good hints. What seems fairly clear is that the point was not that the vast majority of humanity is condemned to eternal conscious torment without divine intervention. And whatever it was, that hard fate, it came to those who oppressed the poor and the weak. It was a consequence of what people did, not what they were.

In the King James translation of the Bible all these various words were near uniformly translated as Hell. And with that both losing the nuancing of the original texts and reinforcing the importance of Hell. But whatever Jesus taught, it began to pass behind the story of his death. And the story that followed, how somehow it fixed the problem, which became not death but Hell. At least for those who believed it fixed the problem.

Much is made of Jesus’ use of the word Hell. In particular two of his parables are cited. The Sheep and the Goats. And the Rich Man and Lazarus. People ignore these are teaching stories, and much in the same spirit of trying to find the timing of the creation of the planet by counting genealogies, it misses the point by literalizing what seems plainly to be an illustration.

In a footnote sort of way, Jesus’ story of the Rich Man and Lazarus is very possibly based on the Egyptian story of Setme and Si-Osiris. There also are variations of the dream in the Palestinian Talmud. The point in the various versions of the story is not literal punishment, and certainly not some eternal punishment, but the vagaries of existence, and the ease in which roles can be reversed. It is a call to humility and generosity.

Interestingly, Paul, who is not my favorite figure in the New Testament, the author or putative author of thirteen of the books of the New Testament, in total a full third of the collection, never mentioned eternal torment. The point of the first Paul is an ecstatic eschatology, it’s about love, much more than about punishment.

In the myths of many religions there are hells. Buddhist cosmology, for instance, posits many hells tailored to individual transgressions. However, these hells in the various world religions are almost always temporary, purgative events. Only in Christianity and its sibling Islam do we get a doctrine of eternal conscious torment.

How Hell as a place or state of eternal conscious torment became a normative belief in Christianity is not entirely clear. In the decades that followed Jesus’ death, a number of different schools arose attached to Jesus’ name. Most passed away, a couple spread.

The scriptures are messy, and it’s certainly possible to find an eternal Hell in the Christian scriptures. The Book of Revelations with its Lake of Fire has captured many imaginations over the many years. The book is a monument to allegory, parable, and metaphor that generations of readers have turned into a literal description. And probably more than any other book of the Bible, it becomes the source for people’s belief in eternal conscious torment. The problems with the book are why it took a long time for it to be generally accepted into the forming canon. The last book to be included in what have become the normative lists.

By the fifth century a normative understanding of Christianity came to the fore, along with some principal minority reports. The majority view was that the majority of people would end up in Hell, a place of torment. Most saw a two-step progression, the immediate death of the individual and then at the end of time a general resurrection, a judgement, and a Lake of Fire, for many another literal.

As Professor Hart said. This idea of eternal conscious torment is “manifestly absurd,” “abominable,” “loathsome and degrading,” “perverse,” “inexcusably cruel,” and “morally corrupt.” The Christian tradition is lovely. In an understanding of sin, a word well worth unpacking, there is a pointing to a facet of the jewel that is our human engagement with hurt. Hell, however, is a worm, eating away at the truths the tradition brings forward for human healing.

The Orthodox and others have found this whole Augustinian, to give it a name, concept of an eternal Hell a misunderstanding. Most Orthodox believe the Heaven and Hell are the same expression of God’s love, experienced as joy or pain depending on one’s willingness to accept it. Others feel there needs to be a Hell, but that no one needs to be in it. Others believe in the annihilation of the unjust.

While others believe some eventual restoration of all to God.