Hildegard of Bingen died on the 17th of September in 1179.

Today this day is observed as a feats for one of most interesting and complex individuals in the annals of Christian mysticism. Itself a complex subject. The mystical life is often mixed up. In any number of ways.

Hildegard was born in the vicinity of 1098 within our common era to a family of “lower nobility,” within the confines of the Holy Roman Empire in what is today Germany. Sickly and afflicted with visions from well before her adolescence her parents enrolled her as an oblate in the Benedictine order. As it happens this seemed exactly what she needed and at around fourteen Hildegard took her life vows. Between her mentor the anchoress Jutta von Sponheim and the monk Volmar, who examined her closely and both felt her visions did indeed contain truths and so they helped the young nun to live with them and through them.

Upon Jutta’s death, Hildegard was elected leader of the community. Eventually she would also found a second community. She became a powerful figure within the religious world of her day with influence that extended beyond her convents. Something it should be noted that was astonishingly rare for a woman in those days and in that place.

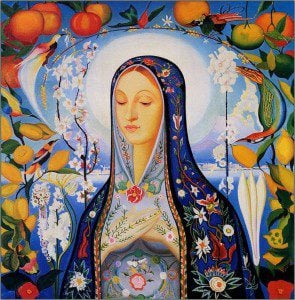

As to the visions, Hildegard reported her experiences started at the age of three. She called it “the shade of the living light,” and described this “light” as something experienced through her conventional senses. Some modern physicians including Olive Sacks reading her detailed accounts of her experiences diagnosed her as suffering from severe migraines. Actually that makes a lot of sense. But, these experiences also, in my opinion, allowed the results of her deeper reflections a means of expression, breaking through societal and religious barriers, and to erupt into consciousness, and, most importantly, given a voice.

These remained private revelations until 1141 when she felt the call to write them down, which she did. She also illustrated them. Critically, the pope Eugenius approved her publication of these visions. And with that approval her teachings began to be shared widely.

Her interests and the subjects of her visions were wide, ranging from medical considerations, to music, to ecology, to natural science, to writing, including among her theological speculations, what some consider the oldest surviving morality play. She continued to break past the conventions of gender and became a popular preacher, taking three major tours to lecture on her teachings. She became counselor to bishops and kings. She even had the pope’s ear.

When Hildegard died she was quickly venerated as a saint by many. And, finally, in 2012 was declared a “doctor of the church,” a signal honor extended to only thirty-five people, and counting her only the fourth woman to be so honored within the history of the Catholic church.

Me, I place her roughly within the family of pantheists, and therefore part of the family I claim as my blood kin. Certainly she saw the power and beauty of the natural world, and whether she genuinely held the dualism inherent in the Christian tradition or it dissolved at some point in her giving herself over to the ecstatic moments of her visions, there is a sense to her that seems to me to sacralize the natural in a way not so common among her co-religionists.

And, you know, in my experience, and by my observation, we all fail in significant ways to find the balance. Although I would throw in it is actually at those spots of failure the way is revealed. We are to compound the mystery only able to ascertain the whole through or actually as our brokenness.

Such is life. Such is the way…

And, all that said, I’m so glad today is an opportunity to pause and recall one of the significant mystics of the Western world, one who looked deep into the broken and saw the beauty and the mystery of the whole.

A gift, actually, to the whole world.