NO THERE THERE

A Dharma Talk

Edward Sanshin Oberholtzer

Drive north from Oakland to the city of Berkeley along Adeline Street and just where BART, the Bay Area commuter line, dives back underground you’ll find one of those sculptures that Berkeley has commissioned to mark the entry points into the city. In this case, two large sets of sheet metal letters reading HERE as you enter Berkeley and, for those benighted souls going the other way, THERE as they enter Oakland; a correction to Gertrude Stein’s famous comment about Oakland that “There is no there there.

While I sympathize with Stein, who was actually lamenting the loss of the old Jewish neighborhood, gone during her sojourn in Paris; I, for one, always found more than enough “there” there in Oakland.

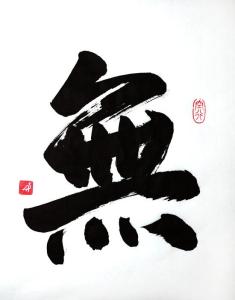

But this brings me to the notion of “there”as place, as extension, as space, infinite, stretching out without end, and, of course, to its correlative term, “emptiness”, for what can we say about our notion of outer space if not that it is vast, and above all, empty.

The emptiness that we often soften with the term boundlessness still has that air of expanse – witness “the Way is perfect like vast space” , the words of the third patriarch in his Xinxinming. I reach deep into the pocket of my pants, grasp the bottom, avoid the lint, pull it out inverted……empty. I drain the bottom of a glass of bourbon and ice, turn it upside down…..empty. I lie out on the grass in the backyard, look deep, deep into the night sky, past the moon, past the stars……empty.I open my hand, there, there at the end of my arm, I open it and let whatever alights there to stay, whatever lingers whatever drifts off to go……….empty.

We think of empty jars, of empty rooms, the Empty Quarter of Saudi Arabia, the vast emptiness of the American plains. Eerie and echoing. Gertrude Stein searching for the there-ness of Oakland, only to not find it. The wind whistling out over the prairie, and yet, and yet it all really misses the point. In case 268 of Dogen’s collection of three hundred koans we find Hsi-t’ang also missing the point:

Master Shih-kung’ asked Hsi-t’ang, a former abbot, “Do you know how to grasp emptiness?”

Hsi-t’ang said, “Yes, I know how to grasp emptiness.”

Shih-kung’ said, “Well, just how do you grasp it?”

Hsi-t’ang reached out and grasped at the air with his hand.

Shih-kung’ said, “You don’t know how to grasp at emptiness.”

Hsi-t’ang responded, “How do you grasp it, elder brother?”

Shih-kung’ poked his finger in Hsi-t’ang’s nostril and yanked his nose.

Hsi-t’ang grunted in pain and said, “It hurts! You are pulling off my nose.”

Shih-kung’ said, “This is how to grasp it.”

Emptiness, true emptiness, the vast emptiness of Bodhidharma’s response to the emperor Wu, is so much simpler than, more wondrous than and, frankly, emptier than this vision of mere space that the word invites us to consider. Words, words can so often lead us astray. Even the alternate, boundlessness itself can carry with it the sense of physical space.

But, that’s not the emptiness that Shih-kung’ found with his finger up Hsi-t’ang’s nose.

My grandfather was a devoted amateur geneologist, and given his education as a mechanical engineer, drafted a marvelous family tree that stretched back generations into medieval Germany, a tree as alive for him as any sapling out in my backyard. Relations…..parents, grandparents, great grandparents, great-great grandparents, uncles, aunts, cousins, so many cousins. All interconnected in that vast web of familial relations, Indra’s web laid out on drafting paper. Relations made manifest each day in each of us. My mother looking at my brother and saying, you have Uncle Joe’s eyes. Me, feeling in the muscles of my own face the expressions that my grandfather would assume. Look inside however much I will, there is no there there and yet I am the sum total of all of those family relations going back to medieval Germany; no, more, the sum total of everyone I have met, of all those the myriad connections that I have had. friends, teachers, strangers. The bluejay in my backyard, the store clerk who waited on me, the author, long since dead, who wrote the novel I just finished. No essence, just relations. And, as distant as that family tree might seem from the Dharma, it comes so much closer to encompassing it than does the boundless track of space that lies just past our atmosphere, or a poor former abbot trying to grasp emptiness in his hand, though each is, in its or his own way, emmeshed in the whole.

And let me say that I am partial to emptiness, as a term, for all of its air of nihilism. It’s not a term that’s easy to defend. I have a friend who says of Buddhism that it is an example of oriental despair, of negativity, pessimism and denial, largely in reaction to that single term, emptiness. Seeing that, reacting to that, fellow travelers on the way often prefer to use other terms. The Boundless is the one that stands out. Me, I stick with emptiness; might as well be hung for a goat as a lamb. It seems so simple. We might blame the subtilty of Indian mathematicians, those wily inventors of the notion of zero, itself merely a point on a number line, perhaps best thought of lying midway between one and negative one, a relational concept much like our notion of shunyata, of emptiness itself. Nagarguna, the poet and scholar of emptiness pointed out that the present makes no sense without the past and future, the middle, no sense without the left and right, the top and the bottom. Nagajuna points us to the ultimate emptiness of emptiness itself in verses from his Fundamental Wisdom of the Middle Way, here in Jay Garfield’s translation:

Whatever is dependently co-arisen

That is explained to be emptiness.

That, being a dependent designation,

Is itself the middle way.

Something that is not dependently arisen

Such a thing does not exist

Therefore a nonempty thing

Does not exist.

Not for Nagarjuna that line from an old Methodist hymn “Change and decay in all around I see, oh thou that changes not abide in me. Even the “thou”, abiding in me changes. A kind of ex nihilo nihil fit, nothing can come from nothing, but with all the phenomenal, all the relative world dancing forth.

We are raised to consider the essence in all things, a core, an inner nature that lingers even when the externals fade away. There is a certain irony in that we talk of Form and Emptiness as two sides to the same coin, yet the word Form carries with it, in Western thought, the whiff of Platonic idealism, of an inner essence itself, and not the 10,000 grasses coming forth. Look for that essence and you find that it has already changed, like the neighborhoods of Gertrude Stein’s Oakland. It was just across the San Francisco Bay from Oakland that Shunryo Suzuki gave his summation of Buddhism in one sentence, “Everything changes”. Even, no, especially, the very nature of all things. Search for that essence and you will come up empty handed, you’ll no more be at peace than the Second Ancestor, who turned to Bodhidharma for relief in Case 41 of the Gateless Gate:

Bodhidharma faced the wall. The Second Ancestor stood in the snow, cut off his arm and said, “Your disciple’s mind has no peace as yet. I beg you, Master, please put it to rest.”

Bodhidharma said, “Bring me your mind and I will put it to rest.”

The Second Ancestor said, “I have searched for my mind but I cannot find it.”

Bodhidharma said, “I have completely put it to rest for you.”

And so the ground on which we stand is pulled out from beneath our feet and we are free to dance, we have no choice but to dance. Chögyam Trungpa pointed out that “The bad news is you’re falling through the air, nothing to hang on to, no parachute. The good news is, there’s no ground.” So, dance as you float.

And so we come back to Gertrude Stein, searching, searching the city of Oakland looking for , and not finding, a there there. Search though she might, Perhaps Bodhidharma could give Gertrude Stein some peace, showing her that, after all, she was right, there really is no there there.