Roma Locuta

In 412, St. Augustine preached his hundred and thirty-first sermon. Referring to ongoing controversy over Pelagius, who taught that divine grace was little more than a good example, he pointed out that Pelagian doctrine had already been condemned by local synods in Africa, and that these judgments had been confirmed by the Pope—twice.

Jam enim hac causa duo concilia missa sunt ad Sedem Apostolicam: inde etiam rescripta venerunt. Causa finita est: utinam aliquando finiatur error.

Already two councils on this matter have been sent to the Apostolic See, and the reports have come back; the matter is closed. If only the error would be closed as well!

This is the root of the saying Roma locuta, causa finita est: “Rome has spoken, the matter is closed.” This used to be a popular proverb with conservative Catholics, though I haven’t seen it from them very often lately. Of course, it is a little glib, and it does simplify the theology an awful lot. Maybe they decided that wasn’t a good look.

So anyway, the death penalty. Lots of Catholics, including some bishops and cardinals, are real butthurt about Pope Francis opposing it. Let’s review.

Of the Background

The Catholic Church used to endorse the death penalty; capital punishment was legal in the Papal States throughout their existence. The basic doctrinal gist was that:

- The state has the right and duty to avenge crimes;

- The state has the right and duty to protect society; and

- Some criminals (e.g. murderers) have forfeited their own right to life.

This may not seem to jive with the idea that human life is sacred, but that fact was marshaled in support of the death penalty. If life is holy, then violating it calls for a terrible recompense, and if it’s true that a criminal has forfeited their own right to life, the death penalty makes some sense. The text Whoso sheddeth man’s blood, by man shall his blood be shed was the classic Scriptural rationale. Modern death penalty supporters, Catholic and otherwise, often use this argument today.

There are other arguments, too. Deterrence is popular—though considering how much people commit crimes in places that do use capital punishment, it seems like a terribly silly argument to me. Some even say that the death penalty may move a criminal to repent. That might sound dumb and fake, but when you look at how much our ancestors worried about “an unprovided [i.e., unforeseen] death,” it starts to make more sense. Dr. Samuel Johnson (though he spoke against capital punishment for lesser crimes than murder) famously remarked, “Depend upon it, sir, when a man knows he is to be hanged in a fortnight, it concentrates his mind wonderfully.”1

So what happened?

Of Life Issues

Among other things, St. John Paul II happened. In his 1995 encyclical Evangelium Vitæ, he didn’t categorically reject the death penalty. But he did say the following.

[T]o kill a human being, in whom the image of God is present, is a particularly serious sin. Only God is the master of life! … There are in fact situations in which values proposed by God’s Law seem to involve a genuine paradox. This happens for example in the case of legitimate defense …This is the context in which to place the problem of the death penalty. On this matter there is a growing tendency, both in the Church and in civil society, to demand that it be applied in a very limited way or even that it be abolished completely. … The primary purpose of the punishment which society inflicts is “to redress the disorder caused by the offense.” …

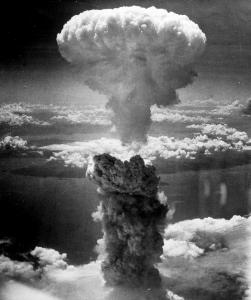

It is clear that, for these purposes to be achieved … [the state] ought not go to the extreme of executing the offender except in cases of absolute necessity … [S]uch cases are very rare, if not practically non-existent. In any event, the principle set forth in the new Catechism of the Catholic Church remains valid: “If bloodless means are sufficient to defend human lives against an aggressor and to protect public order and the safety of persons, public authority must limit itself to such means …”

All of this comes in a letter that mostly reiterates Catholic beliefs about abortion, euthanasia, and other forms of violence. The Pope thus established opposition to the death penalty as a pro-life issue, without calling the death penalty intrinsically evil.2

Of “Inadmissible”

Here’s the thing, though: Pope Francis never called the death penalty intrinsically evil, either.

The famous change to the Catechism (in §2267, for those of you scoring at home) said the death penalty is “inadmissible.” Several Catholic authors have said this is “vague,” but in context, it really doesn’t seem that hard to follow. Here is the text of the altered paragraph in full.

Recourse to the death penalty on the part of legitimate authority, following a fair trial, was long considered an appropriate response to the gravity of certain crimes and an acceptable, albeit extreme, means of safeguarding the common good.

Today, however, there is an increasing awareness that the dignity of the person is not lost even after the commission of very serious crimes. In addition, a new understanding has emerged of the significance of penal sanctions imposed by the state. Lastly, more effective systems of detention have been developed, which ensure the due protection of citizens but, at the same time, do not definitively deprive the guilty of the possibility of redemption.

Consequently, the Church teaches, in the light of the Gospel, that “the death penalty is inadmissible because it is an attack on the inviolability and dignity of the person”, and she works with determination for its abolition worldwide.

In other words: the circumstances that could justify resorting to capital punishment don’t exist any more; therefore, it’s now wrong. In much the same way that, say, continuing to wage war on a country after it surrenders would be wrong.

Of Violence

This isn’t relativism, or a lack of respect for tradition. It’s an example of applying the principles of Catholic theology to a new situation; that’s really very normal. It’s especially normal when we’re talking about violence. Violence is a moral issue that’s extremely context-sensitive; but the common thread you find running through Catholic discussions of self-defense, just war theory, and so on is: even when violence can be justified, only the minimum amount of it is morally lawful. Using more violence than you have to is culpable. And killing when you don’t have to is murder—whether it’s legal or not.

Because the point is to protect life and safety. Not to find pretexts to gratify our anger and pride. Being more violent than protecting people actually requires? That’s not noble. It’s not heroic. It’s self-indulgent. Though it is, in a sense, traditional; most sins are.

Of Butthurt

The usual suspects have been accusing His Holiness of defying the tradition of the Church. I’ve seen people on social media brag about ignoring the Pope, or try to cite previous councils and set them against him. Never mind the fact that the relevant section of the Catechism states that this is not only a development of doctrine, but one that depends partly on circumstances—we have means to protect people without using the death penalty today, which a lot of earlier societies didn’t.

A few people, notably Cardinal Burke, have even made the shabby and bad-faith argument that this is Pope Francis “speaking as a man” (i.e., expressing his personal opinion) and not an exercise of his teaching office. Because of course, if it were an exercise of his teaching office, they’d have to accept it. Honey, when the supreme pastor of the Catholic Church makes a change in the Catechism, complete with an explanation of both doctrinal and historical reasons he’s making it, he is obviously teaching. There is no wiggle room available. This is just what words mean.

Causa Finita Est

Hence my allusion to heresy in the title of this post. Because heresy isn’t just believing wrong things. (If it were, a lot of saints would be in trouble, including several doctors of the Church.) It is refusing intellectual obedience to an authority you recognize as divine. Which, yes, includes deciding that you don’t recognize that authority any more because you don’t like what it says.

Having a hard time understanding Catholic teaching is not a sin; some ideas are difficult. Having a hard time believing Catholic teaching is not a sin; faith is both a gift, and a habit built of long practice, and neither of those things come on command. But, at any rate if you’re a Catholic, appointing yourself the arbiter of what is and isn’t genuine Catholic teaching is blatant hypocrisy. And ragging on Catholics who defend abortion or gay marriage as heretics, while you yourself defy the Pope on other matters, is hypocrisy atop hypocrisy.

It is necessary to remember what Dante meant by heresy. He meant an obduracy of the mind; a spiritual state which defied, consciously, a power ‘to which trust and obedience are due’; an intellectual obstinacy. A heretic, strictly, was a man who knew what he was doing; he accepted the Church, but at the same time he preferred his own judgment to that of the Church. This would seem to be impossible, except that it is apt to happen to all of us after our manner. … A heretic, strictly, was a man whose integrity of mind had disintegrated; he justified error and evil to himself, and propagated the justification.

—Charles Williams, The Figure of Beatrice pp. 125-126

Footnotes

1I’d be misleading you if I implied death penalty advocates are always thoughtful, smart people operating in good faith. But I don’t consider it worth my time to answer the other sort of person, not intellectually anyway. Besides, there are thoughtful, smart people operating in good faith who support capital punishment, or who at least have (sincere) questions, and they do deserve acknowledgment.

2Intrinsic evil is an important technical term in Catholic moral theology. If an act is intrinsically evil, it is wrong in and of itself, no matter what. No circumstances can or ever could justify it. (This is a different question from how culpable a person is for doing it, which does depend partly on circumstances.)