Earlier assignments in this course: I Can’t Believe It’s Not Fascism, Good Country Volk

There are a few traits that fascism and Catholicism share (or seem to share) that can make Catholics easy prey to fascist propaganda. These vary a little, depending on the time and place the fascists are operating in. Here are six key ones.

1. Heritage

Both Catholicism and fascism lay great emphasis upon what we have inherited from the past. Catholics believe in a sacred tradition of beliefs and sacraments, sustained by a lineage of priests that can trace themselves back thousands of years. Fascists believe in a racial identity—sometimes concentrated into something specific like being “Aryan” or “Nordic,” often just “white”—that has a heroic history behind it and a destiny before it. The fact that a lot of motifs (like crosses) fit easily into the paraphernalia of both groups certainly helps.

Nonetheless, there are subtle yet vital differences. Note, for instance, the difference between “heritage” and “tradition.” Heritage implies something you have a right to, based on your family. Tradition suggests something closer to an idea (or even a story), passed on from one generation to the next, yes, but not necessarily with the restrictions a heritage might carry.

In the US, there’s also a slight catch with this one, at least in theory. In terms of culture and history, this country is overwhelmingly Protestant, and harbors a lot of anti-Catholicism. (Besides Blacks and Jews, Catholics were a common target of the Klan.) However, plenty of fascists are capable of putting anti-Catholicism on the back burner, at least long enough to recruit Catholics.

2. Style

I chose the word style instead of beauty here. Some fascist motifs, like some Catholic relics, are rather ugly. However, they’re ugly in a way that commands attention. Fascists operate on, and often have a good grasp of, the importance of æsthetics. Nazi propaganda against Jews and “degenerates” was not meant to be attractive, but it was meant to be eye-catching; beautiful might feel like the wrong word for Hugo Boss, but stylish or sexy would definitely do. The point of all this is that it encourages emotions that fit comfortably with fascist rhetoric. Stirring up hatred against your Jewish neighbor works a lot better if, when you look at him, you’re imagining a hunchbacked, smiling figure with a giant hooked nose who seems at once vile and ridiculous. Images bypass reason pretty easily, and most people have not been trained to reason well in the first place.

Obviously, Catholicism has similar ties to æsthetics. Art and ritual are key to Catholic life, worship, and thought, and the Catholic “brand” is pretty recognizable. The role of the Middle Ages—to be more accurate, the role of how we today imagine the Middle Ages—is also important. It’s attractive to a certain kind of Catholic because it represents an age when Europe was Catholic; it’s attractive to fascists because it represents an age when Europe was white.1

Note, an accent on style is not itself bad. Every movement, school, idea, or institution that has any appreciable social success and history is going to have a style; that’s how human beings are. What is bad is when (a) æsthetics replace thought, and/or (b) they promote something that is false, destructive, or toxic. If you fill a high-end wine bottle with arsenic, the wine bottle is not the real problem: the relationship between the bottle and its contents is the problem.

3. Family

The culture war for the last forty years has been about two main things, gay marriage and abortion. Catholic teaching on the right to life and the nature of marriage sets them in opposition to both these things. Non-fascist conservatives, Catholic or not, tend to frame both of these issues in terms of family values (and the GOP has made a decreasingly convincing pretense of caring about these family values, as a way to secure themselves a voting bloc).

Fascists also tend to hate these things, but for different reasons. Racism and paranoia tend to go hand in hand, and, as we discussed briefly last time, a standard element of fascism is the belief that the “white race” is in danger of extinction. Therefore, fascists typically object to both abortion and non-procreative sexuality (including celibacy), if we’re talking about white people. But, if they’re talking to a Catholic, they’re going to stress the superficial agreement and not mention the racial qualifier.

4. Authority

The Catholic Church obviously has kind of an authority thing. Christ, who was literally God, gave authority to the apostles; bishops are the apostles’s heirs, and the prince of bishops, the Pope, is infallible.2 The power to define religious and moral truth, in a way that (according to the Church) has the right to shape the consciences of others, is colossal. And let’s face it: having an authority feels really nice sometimes. It gives you a sense of security, safety, discipline, and purpose.

Fascism has the same atmosphere. The difference is that the atmosphere comes first. Authority in fascist groups usually comes from personal charisma, not institutional procedure. (Incidentally, this is partly why fascists can so handily manipulate democratic societies; it’s easy to win elections of charisma, and once you’re in power it’s usually easy to tweak the very structures of institutions to align with your goals.) But people who are hungry for an authority figure don’t tend to care a lot about procedures. The hunger is an emotional need, not an idea.

5. Conspiracies

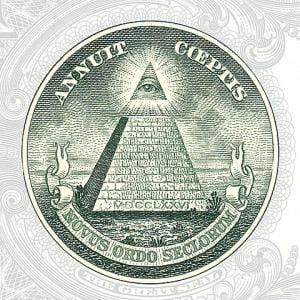

Catholics and fascists both have a long history of scapegoating certain groups of people. Conveniently enough, they are in several cases the same groups of people: Freemasons, Jews, and (occasionally, as a treat) capitalists.

Catholics do this partly for ideological reasons. The theological basis of Christianity, the Incarnation, is something that most Jews reject; Masonry tends to be indifferentist about religion; and, though this is a well-kept secret in the US, the Church rejects capitalism. But there is also just the normal human tendency to blame other people for problems, and to believe that people you don’t like dislike you back. Rationalization and self-justification are among man’s most enduring and universal hobbies.

This doesn’t make Catholicism inherently conspiratorial. The Church teaches that certain ideas are wrong, but she does not teach that specific groups of people are to blame.3

But fascists do. Jews and non-white races are, they claim, conspiring against white people. Fascism not only inflames the human taste for witch hunts, but plays on the witch-hunting past of Catholicism, trying to paint it in the most positive light possible: first by downplaying it (“No one’s saying the Holocaust didn’t happen, it just wasn’t six million people”), then by excusing it (“In a way, the Crusades were self-defense”), ultimately by glorifying it (“Franco brought Spain back from the brink of atheism”).

6. Heroism

There was much merriment on Twitter a while back when someone contemptuously described Catholicism as a “gold-encrusted death cult.” Sounds badass, right? Well, there’s a double edge here.

The Catholic version of being badass finds its pinnacle in martyrdom—dying for faith, hope, and love. The cult of the saints memorializes them, and a lot of macabre elements in Catholicism come in through their stories and relics.

The fascist, however, has a cult of the warrior. Death in battle is the ideal: a death for nation, destiny, and glory. The warrior and the martyr are superficially similar in their courage and (in a sense) their selflessness. If you frame the warrior as defending his people—whether he really is or not makes no difference—you can even get the images of warrior and martyr to coalesce. And this, again, has a long history in Catholic culture, starting with the Crusades and the Reconquista. It’s easy to make fascistic violence morally plausible by framing it in these terms.

Later assignments: Children of the Sun, “The Great Replacement”

Footnotes

1Both of these ideas are somewhat mythical. It’s true that Catholicism was culturally and politically powerful in the Middle Ages, but Christians then as now were incessantly complaining about the shocking decline of religion. As for race, it’s true that Europe was less diverse. But there is no time in recorded history when any society was completely homogeneous, racially or otherwise. And any “white” person from the Mediæval period would have laughed in your face if you’d told them that the English and the Irish were “the same race,” let alone peoples more distant.

2Under specific conditions, yes, but even that is a pretty shocking assertion.

3I say this not to minimize the real damaging conduct of many prelates, but simply to distinguish that conduct from the belief of Catholics.