Twenty years ago today. It’s strange that this anniversary feels so normal; probably because it’s been so remorselessly present in American culture all this time.

We have spent the last twenty years at war. That’s all of my teens, plus my whole adult life, after a decade of peace in the 1990s (and that was after an even longer interval that succeeded the Vietnam War). We’ve seen mounting suspicion of Muslims—we went from George W. Bush, whatever his faults, saying within days of the attacks that Muslims around the world are not our enemy, to President Donald Trump saying on national television, “I think Islam hates us.”

Justifiably or not, the machinery of the state has vastly expanded in the last twenty years as well. And that cannot be laid solely at the feet of either party. State monitoring of private citizens was authorized by the Patriot Act; the Bush administration used and defended torture at Guantanamo, and the Obama administration did not close it down; and the brutal enforcement of immigration laws that began under Obama continued and became even more shockingly callous under Trump, nor are there clear signs it has lessened or will lessen under Biden, though it is at least not getting worse (as far as I know).

After a while you just get too tired to be shocked any more. That doesn’t have to keep you from acting; it shouldn’t. But the public performance of outrage is, while not always hypocritical, not always very useful, either. It has some good uses, but one of its bad ones is to give us a feeling of virtue without the cost of action.

Still more dispiriting has been the corruption of the Catholic Church. I love my country, but I never expected very much from it; every nation is a fallen and temporary thing, run by fallen people whose best intentions will always be at least a little tinged with self-interest. I had, however, hoped for more from my holy Mother. To watch so many of the Church’s hierarchs parade their subservience to that order in exchange for a veneer of cultural support made me sick; to discover how many of them had concealed, or even personally committed, the vilest forms of sexual corruption upon the very flock entrusted to them—that beggars description.

I suppose we have the misfortune of living in interesting times. I hadn’t intended to write such a jeremiad when I sat down. I don’t know what I meant to do, really.

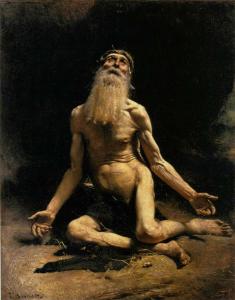

Léon Bonnat, Job, 1880

For the last several years, I’ve been thinking a lot about the book of Job. It’s an arresting work. It is the only place in the Bible, I think (with the arguable exception of Romans) where theodicy is explicitly broached, and it is there rejected. God does not deign to vindicate himself, and the pious three who do attempt it are rebuked in no uncertain terms: Ye have not spoken of me the thing that is right, as my servant Job hath. It’s a shocking text for any religious person. To believe in a good and all-powerful Being implies that It has some good reason for not stopping evil in its tracks, and the only scriptural figures who try to articulate such reasons are denounced as sinners who may not even make their own atonement—God tells them to ask Job to intercede for them, and he, God, will listen to that prayer rather than theirs.

On one level this is quite familiar. The everything-happens-for-a-reason crowd are not just insufferable; they trivialize evil. It makes sense that that kind of insulting sentimental nonsense would be an offense against any God who cared about humanity at all. I very much sympathize with the atheist to whom theodicies are an outrage against compassion, an outrage against the real dignity of man and the real vileness of evil.

And when I say that that is where the Cross comes in, there is a terrible danger: the danger of letting a phrase like “Oh, it’s part of the Cross, it’s a mystery” pass one’s lips. Because of course the one thing the insufferably pious don’t sincerely think about the Cross is that it’s a mystery. They think it’s an answer. Even with the Resurrection, I increasingly think that the Cross is not an answer to the problem of suffering at all. If Christ shared our suffering, then he shared our sense of meaninglessness, of futility. That sensation has been raised to the level of the Godhead. It is not to be blasphemed with sentiment.