What Were We Talking About?

Okay! With all of that as setup, let’s begin. The original question was this: If the Church truly means the motte, why set up the bailey? The bailey, you’ll recall, was a lot of Catholic rhetoric and sound bites: stuff like “the Pope is infallible” or “the brown scapular protects you from going to hell”; the motte was the theological explanations, which tend to come off as “well, the Pope is only infallible when it suits us,” or “the brown scapular does protect you from going to hell, unless of course you’re going to hell.”

I think any reasonable person would be annoyed and put off by these useless unsplanations. But I don’t believe the Catholic faith stands or falls with these fallacies. There is better to be had. I think these bad explanations are Catholic-specific examples of more general human problems: thinking in catchphrases, and being stupid.

Technicalities in Exile

We’ll start with catchphrases. These aren’t necessarily bad; they can be useful ways to summarize ideas. If an idea is complex or subtle, it may be inordinately hard to remember without a catchy summary.

However, they come with a kind of problem. When they’re used in their native context, as a way of summing up a longer and better explanation, catchphrases are fine—or at any rate they can be judged on their usefulness to the people using them. But if they’re lifted from that context, they may be highly misleading to people who don’t have the related background. (There’s a parallel here with academic language: terms like cultural appropriation or emotional labor have totally different meanings in academic discussions than they do on Twitter.)

Worse, these decontextualized summaries tend to become stock answers. Teachers or apologists reach for them, because they’re fast and they sound good—to the teacher or apologist. The problem is, the catchphrase was not designed to explain the truth; it was designed to refresh the memories of people who’d already received an explanation of the truth. This is a big part of how you get speakers and writers who are hailed by Catholics as magnificent explainers of the faith, but who leave non-Catholics puzzled or actively repelled.

Goody Two-Shoes

Other issues branch off from here too. For instance, the smart, vain, well-behaved child in religion class (especially if they have a knack for writing) will easily absorb catchphrases, and may even coin some of their own—instead of learning the theology those phrases were meant to represent. Often enough, they have no idea they haven’t learnt it. And nobody hates being shown up more than a pious brainiac, so ego moves them not to learn because they think they know already.

If they’re very unlucky, they might become religion teachers in turn. Not only does this perpetuate the cycle of failure to learn theology, since their students probably won’t be able to make much of their teacher’s ignorance; it can even produce an environment hostile to learning. Because in that setting, the child who is both smart enough to realize how little the catchphrase conveys, and also interested enough to ask about it, is suddenly in danger of embarrassing the teacher. It is not a coincidence that these teachers are apt to accuse their students of “irreverence”; their error lies in thinking that they are angry about irreverence to God, when it is in reality irreverence for their self-image.

Pie Us Bull Leaf

The other issue is simpler: a lot of people run their mouths about Catholicism who just don’t understand it very well. A lot of the time, they’re wrong about theological or historical fact; other times, they’re wrong about how important, or even how certain, a given belief or practice is in the first place. This often coexists with the goody two-shoes problem, but the reddit atheist and the scholar dabbling in fields they don’t understand are equally prone to it. (All these types have similar issues with ego; the main difference between them is what sort of people they want to impress.)

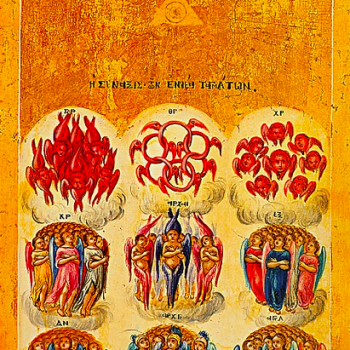

Apparitions are a great example. The appearance of Our Lady at Fátima, Portugal in 1917 has been confirmed by the Church to be “worthy of belief.” But what does that mean? It means there is nothing in its message that contradicts Catholic doctrine and morals; it doesn’t mean that all, or indeed any, Catholics must believe it. It belongs to the class called pious beliefs. Pious beliefs are consistent with the faith and judged licit by the Church; but any Catholic is equally free to find them implausible or unhelpful, and ignore them accordingly.

The thing is, some people have a sort of addiction to purported miracles, or to miracles in general. These may lavish a kind and degree of fervor on these optional extras that they do not really merit; they may treat their favorite devotions as litmus tests of orthodoxy or of holiness, which they most certainly are not. If they are apologists, such people often become obsessed with proving Catholicism on the grounds of how supposedly irrefutable the miracle of the sun is or how inexplicable the details of the Shroud of Turin are—despite the fact that the Church got on perfectly well for just shy of two thousand years without the miracle of the sun, or that the Shroud of Turin is not nearly so clear or informative a witness about Jesus as, say, the Gospels.1

Quo Introis, Domine?

But why would God let all these errors plague the Church? Don’t these arguments amount to excuses for one of the biggest motte-and-bailey setups of all, the one about infallibility?

I don’t think so; and I’ll tell you why. Whether you find the following solution satisfying is, of course, up to you.2

If divine revelation is to be maintained among human being, who are bad at that sort of thing, I do think the only surefire means is an institution that infallibly preserves it and continues throughout time.3 However, the thing about an infallible office of any kind is, it’s incredibly hard, conceptually, to reconcile that kind of thing with the freedom of the human will. And we know only too well that there are bad clergy who will happily use their authority to their own advantage!

My opinion—and it is only an opinion, a pet theory about how this works—is that the Holy Ghost’s gift of infallibility “interferes with” the natural decay of the institutional Church just enough to preserve theological accuracy at the “official” level. My hunch is that this is the most that can be done to preserve the Gospel without either: (a) throwing a Second Coming, which we’re getting to but we have to have something in the meantime; or (b) obstructing human free will in some way, which God seems keen not to do.

And whether we think God grants the Church and the Pope infallibility or not, he clearly doesn’t give it to all Catholics or to human beings in general. So it does stand to reason that people would be able to take the material of the faith and be just as goofy and terrible with that stuff as we have with everything else at our disposal.

Storming the Bailey

What, then, of the recurring problem of the motte-and-bailey? I think the solution here is somewhat tedious, but reasonably easy to practice. It has three steps:

- Pray

- Read/listen to your Bible regularly

- Check every purported Catholic idea against the Catechism

The first two are important ways to foster your relationship with God—which, after all, is the point of Catholicism. Both are neatly fulfilled every time you attend the liturgy, but can still be done outside of it as necessary.

The third is, more or less, what the Catechism is for; it’s a compendium and a reference work. Ideally, it should work a little like Wikipedia at its best, giving you a general sense of things while also pointing you to good source for learning more. It does, incidentally, suffer noticeably from the needless Latinisms addressed in my last installment. (I suggest reading C. S. Lewis’ severely underrated Studies in Words to help limber your brain up for spotting them.)

The corollary of this third idea is: when somebody says that this or that or the other thing is “the teaching of the Church,” don’t take their word for it. This is very boring and annoying, but the brute fact is that when it comes to Catholic teaching, lots of people are ignorant, biased, or both. Lots of Catholics are in this position—and the ones who moan about how bad catechesis is these days are no exception. Test the spirits; hold fast to what is true.

Footnotes

1I chose these two examples not because I’m skeptical of them, but because I incline to think they’re probably legitimate. But that’s the thing: if I’m wrong about either or both, it has no implications for my faith at all. They’d just be neat things I happened to be wrong about.

2And I wish to stress that, insofar as it plays any role in apologetics, it can only be as an answer to the quite reasonable objection that this seems like a terrible way to run a Church. It is not a positive argument for Catholicism.

3The Protestant alternative to this institutional solution, namely sola Scriptura, is not without merit. However, I ultimately came to find it unsatisfying for a number of reasons, one of the chief ones being that Scripture cannot develop over time. People can apply it to new circumstances, yes; but that new application can only be as authoritative as the interpreter. This means that as time goes on, the infallibility of Scripture becomes less and less relevant to our lives—unless there is some designated interpreter who enjoys a peculiar gift of authority to judge applications of Scripture.