And they worshiped the dragon which gave power unto the beast: and they worshiped the beast, saying, “Who is like the beast? Who is able to make war with him?” And there was given unto him a mouth speaking great things and blasphemies … And I beheld another beast coming up out of the earth; and he had two horns like a lamb, and he spake as a dragon. And he causeth the earth and them which dwell therein to worship the first beast. —Revelation 13.4-5, 11-12

Let Us Not Join With One Achord

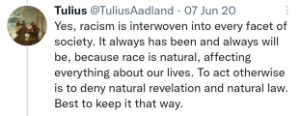

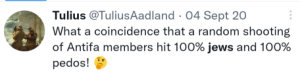

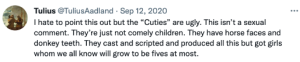

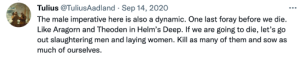

I don’t know how far this news has spread off Twitter, but Thomas Achord, a friend of Dr. Stephen Wolfe—Princeton professor and author of The Case for Christian Nationalism—has made something of a splash there. Until quite recently, Achord was the headmaster of a classical school in Louisiana. He resigned due to the discovery of certain, let’s say, unflattering decisions he made on his social media, particularly a Twitter alt named “Tulius Aadland.” This account shared many charming and devout sentiments like the following:

I won’t disgust my readers with further evidence. (Those who wish to do a little more investigating to satisfy their sense of justice might look to this post by Alastair Roberts; Roberts is himself quite conservative and therefore unlikely to stack the deck against Mr. Achord.) Suffice it to say, the storm began.

Apologish

At first, Achord claimed the offending account was not him. A number of his friends, Wolfe included, ran to his defense. This turned out to be a lie; Achord admitted as much as the evidence piled up around him. He made a somewhat rambling public apology after being found out.

This is understandable, of course. I have my share of secrets I’d be so ashamed to confess to even after getting caught that I’d be strongly tempted to lie about them. And if Twitter has ruined anything, it is the appropriate public apology; pile-ons encourage panic, not reflection or repentance. In any event, while the apology did not impress the public, it did make an impression. The American Conservative had some choice words to share:

In 2020, he published a book he co-edited, one that has a big section of passages buried in the middle arguing for the virtues of segregation. … [On his] Goodreads account, years ago, he was recommending Mein Kampf, the autobiography of David Duke, and other gems …

The reason some of his friends say it doesn’t sound like him in real life is because not everybody knew him online. … [P]eople who have a dark side can hide pretty easily online, especially if by their outward presentation, nobody suspects that they might have a shadow life. … “Father was such a nice guy, I just didn’t see that coming.” …

This is cowardly. You were an online racist, anti-Semite, woman-hating creep who admitted on that account to wanting to use Classical Christian Education as a Trojan horse for white nationalism—and did this while you were the headmaster of a school that trusted you! … This does not come a thousand miles near the apology and contrition you owe to the faculty, students, and parents whose trust you betrayed …

And that’s from Rod Dreher, whom I don’t think anyone is likely to accuse of mere irrational prejudice against right-wing Christian nationalists.

A Wolfe in a Sheep’s Dust Jacket

Okay, this Achord guy was bad. So what? Well, one of the other things that made a splash on Twitter shortly before this was a newly-released book by Dr. Wolfe: The Case for Christian Nationalism. He has argued that people are treating Achord unfairly (by, uh, pointing out the things he said), in an equally unfair attempt to discredit his book.

Now, I agree it’d be ludicrous to imply that either The Case for Christian Nationalism or its author must share Achord’s revolting attitudes merely because the two are personal friends. However, to the best of my knowledge, nobody’s doing that. What a great many people are doing is pointing out that the two men are not merely close personal friends. They’re co-hosts of the religious podcast Ars Politica, and moreover, Wolfe followed Tulius Aadland on Twitter until fairly recently. Returning to Dreher:

[E]ven if attacking Achord was “all about discrediting [Wolfe] and [his] book” from the beginning, I’d say that they found the right target. … They are professional associates. There is documented evidence … Wolfe followed Tulius Aadland; are we really to believe that he had no idea that his podcast partner and friend was really Tulius? And anyway, why would he follow such a persistently vicious, racist, Jew-hating Twitter account? … I’d say it’s perfectly fair to ask what he knew and when he knew it. … This controversy is not going away, no matter how badly Wolfe’s publisher, Canon Press, wants it to.One big reason it’s not going away: nowhere in Wolfe’s statement does he once repudiate the flat-out racism, the Jew hate, the ugly misogyny, of Achord. Nor, for that matter, does Achord … Wolfe acts as if … now that Achord has confessed his lie, that wraps things up. No it does not! You can’t be so closely associated in your professional activities with a radical racist and not have it call your own morality into question.1

Disclaimers

I can freely admit that I would have been prejudiced against Dr. Wolfe’s book in any case. If there is any single idea I’ve always regarded with hostility and distrust, it’s nationalism. My mother raised me and my sisters on authors like Corrie ten Boom, Elisabeth Elliot, and C. S. Lewis2; we always had a clear, vivid sense that the kingdom of heaven came first, and that any human society or cause was decidedly in second place at highest. I’ve always seen the nation as one of the strongest and oldest possible rivals to God that there is, nor do I believe it’s a coincidence that the first pagan persecutions were about burning incense to Cæsar.

However. I’m the first to admit that the Church has not technically issued any anathemas against nationalism. There are plenty of ideas that may be false or dubious but are not specifically un-Catholic; a flat-earther or cryptozoologist may be stupid, but this does not make them heretics. I’m not going to pretend that simply pointing out the title of The Case for Christian Nationalism constitutes an argument against it (badly though I might want to).

Diagnostics

Here’s the thing, though. The reason I loathe nationalism so much (and sometimes find it hard to write about) is that it makes errors about Christianity that are so basic, it’s really hard to believe that nationalists are paying any attention to the gospel at all. How do you read the Sermon on the Mount and think that your Christian faith is compatible with militarism and authoritarianism? How do you read the Passion narratives and think that the best thing for a follower of Jesus to do is try to amass power? I stop short of calling nationalism a heresy; but I’m perfectly ready to remind my readers that even the demons believe there is one God, and disguise themselves as angels of light. Nationalism is a corruption of Christian faith, and not just in specific cases but in and of itself.3

In particular, due to its own inner logic, Christian nationalism in America runs into the following problems:

- It misunderstands what ethnicity and race are, and what importance they can have.

- It grossly distorts the relationship between nature and grace, both by confusing them with each other and by largely ignoring human sinfulness.

- In consequence, it grossly distorts Christian ethics; and, partly for this reason,

- It tends to ignore the eschatological side of Christianity (i.e., death, the Second Coming, and eternity).

- It tends to rely on a myth of our history that’s overwhelmingly false.

Let’s go through these problems, one by one.

Footnotes

1It may feel a little surreal to see Dreher making statements of this kind, given his own political associations and the degree to which he seems unable or unwilling to reckon with what they imply. But of course, one of the things about the beam in one’s eye is that it is precisely too close to see; the mote in our neighbor’s generally sits in a more convenient range.

2If he seems like an odd inclusion in this context, I strongly recommend his novel Out of the Silent Planet and his essays “The Seeing Eye” and “Religion and Rocketry.” He is famous for the Talking Animals and mythological creatures of Narnia, but it is easy to assume he made these merely because they’d be fun for children; in truth, characters like Mr. Tumnus and Reepicheep are only the tip of the iceberg.

3I’ll qualify this as far as to say that nationalism can and sometimes does operate differently among national minorities, especially if they have no independent nation to call their own, like the Kurds. I don’t know enough about these situations to say much about them, but they also aren’t what we’re talking about when Christian nationalism in the US is under discussion.