But when he had turned about and looked on his disciples, he rebuked Peter, saying, “Get thee behind me, Satan: for thou savorest not the things that be of God, but the things that be of men.” —The Gospel According to St. Mark 8.33

The Story So Far

Previous installments in this series include Christian Nationalism; or, The Voice of the Dragon and After These Things Do the Gentiles Seek.

Christian nationalism hasn’t been declared a heresy, but perhaps it should be. Its associations in America and western Europe are a bit off-color (the tint of their hoods notwithstanding), and the theology it generally espouses is extremely warped, both by false premises about biology and history and by misapplying genuinely Christian doctrines.

The release of Stephen Wolfe’s book The Case for Christian Nationalism inspired me to tackle this subject. My jumping-off point for this series was the recent scandal over Thomas Achord, the former head of a Louisianan classical school who was forced to resign after exposure as the person behind a graphically racist and sexist Twitter account—and a man with many links to Wolfe, who has spoken out both sides of his mouth about both Achord and their friendship.1 (Achord’s downfall was also interpreted by him as an attack on him and his book, as contrasted with being an attack on the anti-Semitic, woman-hating, and sometimes nauseating sexual remarks which characterized the account in question.) In my last post, I discussed the biological errors involved in the very idea of race, which is a key element in most versions of nationalism; let us now turn to the more strictly doctrinal issues.

Note that, for the sake of simplicity, I’m not going to address the differences between Dr. Wolfe’s denominational distinctives in general (he is a Reformed believer, a.k.a. a Calvinist) and those of the Catholic Church. Though many of those distinctives do rise to the level of heresy2 on the Catholic view, almost none are germane to this topic. Besides, it isn’t as if Wolfe is personally to blame Christian nationalism, which has existed for centuries and is present in lots of denominations.

De Rerum Natura

You may have heard or read Christian nationalists repeating phrases like “grace does not destroy nature” and “your natural desires are not evil.” Just a day or two ago, Corey J. Mahler (a nationalistic Lutheran writer) tweeted, “There is Jew and there is Greek; there is slave and there is free; there is man and woman.”

These go back to a quite orthodox epigram which, to my knowledge, began with St. Thomas Aquinas: Gratia non tollit naturam sed perficit, or “Grace does not take nature away, but completes it.”3 The proverb is a great favorite among Christian nationalists, such as Wolfe. They use it to argue that our preference for our own race, or at least for our own ethnicity, is natural and therefore, apparently, above critique. (They also spend a lot of time insisting that this preference for our own exists and is universal, so vehemently that I can’t help wondering whether they really believe it.)

I won’t go back in detail over the reasons all ethnicities are fuzzy around the edges and why race basically doesn’t exist. Those facts are relevant to why the nationalist argument based on this slogan doesn’t work, since a preference for something that isn’t real is a preference of nonsense to fact. But that isn’t the theological problem with the argument; that lies elsewhere; in fact, it lies in the doctrine of sin.

We Need to Talk About Morgan4

I’m not above taking a certain grim amusement in the fact that men like Wolfe and Mahler, a Calvinist and a Lutheran respectively, are the ones throwing out the message of Scripture—to the point of literally rewriting a famous maxim of St. Paul, and from Galatians—in order to justify their favorite superstition with the aid of a slogan from St. Thomas Aquinas of all people. It is also ironic that nationalists affiliated with these Protestant traditions, which so love to accuse Rome of Pelagianism, will now be accused in turn of a kind of Pelagianism, by me.

The word nature comes from the Latin natura which in turn comes from the verb nasci. This verb means “to be born; arise, grow.” The concept of “the natural” therefore came to mean “what happens by itself” or “what you’ll find if a thing has not been interfered with.” We can contrast this with a few different things: the unnatural, for instance, which generally means “what has been interfered with specifically for the worse”; also the supernatural, a hard word to define, but which might be described along the lines of “what is above or immune to being interfered with.”5 We’d therefore assume that human nature means “what human beings are like, all else being equal.” But when we enter the realm of Christian theology about humanity, we run into a catch in this pleasingly simple setup.

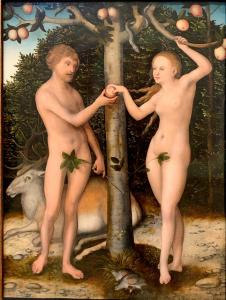

That catch is the doctrine of original sin, which the fifth-century monk Pelagius gained infamy for denying. Without exploring the details or interpretations of this doctrine,6 we can summarize it as all human beings having a bad moral outfit from birth, one that is inclined to serve its own interests and desires. This is despite the fact that man was originally created for fellowship with God and had a moral outfit to match, one that may have been immature but was inclined toward him before all else.

This makes talking about “human nature” since the Fall a little ticklish. On the one hand, humanity as such has to be basically good, on any Catholic view: not only did God make man, humanity literally could not exist if it were basically evil, because evil is parasitic and has no independent being. On the other, all human beings whom we actually meet are corrupt specimens of our kind, due to original sin. And, while bad examples do harm of their own, original sin is not simply a bad example imitated and thence hardened into habit—that error was what Pelagius taught, and the Church laid its official “Nah” on that idea at the Councils of Jerusalem (415) and Carthage (418). It is a disposition to self-centeredness that exists before any example is intelligible to us; we carry it with us from birth like a hereditary disease.

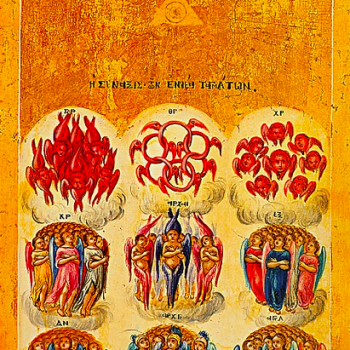

The Gospel of Thomas

This distinction, between humanity qua humanity and humanity since the Fall, is crucial to St. Thomas’s maxim about grace and nature. It’s plain nonsense to say “grace doesn’t take away nature” if we’re talking about original sin—in the Catholic doctrine of baptism, the entire point of the ritual is that it does “take away nature”! What Thomas is talking about is the goodness of human nature apart from sin; the disease, though universal and inborn, is curable, and the cure does not make the baptized ex-humans or require them to give up their humanity. This was a point well worth making in the thirteenth century, as distorted forms of and motives behind asceticism were rampant, both within the Catholic Church and among heretical fringe groups.

Gratia non tollit naturam is also a useful saying in the spiritual life, because devout people are apt to go overboard while learning the highly demanding virtue of temperance. This often leads them to blame aspects of themselves they don’t like or aren’t comfortable with for their sins—which, incidentally, is the real problem with interpreting the text about If thine eye offend thee, pluck it out literally: the issue isn’t that Jesus would never ask us to do something so costly and painful, but that it is not in fact your eyes, nor any other body part, that commit sin.

But it’s also a slogan that’s open to abuse, because sin is “natural” too. Therefore, when discussing human nature, we need to specify (to our own minds and to our audience) which one we’re talking about. Is it human nature in the sense of “what God made humans to be,” what we might call the Platonic Form of man, which involves no moral corruption? Or is it human nature in the sense of “humans as they inevitably are in a post-Fall context,” which does involve such corruption, and is also the only sort of human most of us ever encounter directly?

“Natural Instincts”

The way Christian nationalists use gratia non tollit naturam depends on confusing these two senses of the term nature (whether because they are honestly confused themselves or because they’re deliberately being deceitful). This is an example of a standard logical fallacy, equivocation: leaving out distinctions in the meaning of a word that are relevant in the context of the argument the word appears in.7 And the distinction between these two senses of nature, between “not interfered with by God” and “not interfered with by sin,” is a pretty colossal one—indeed, inasmuch as it’s about redemption from sin, Christianity claims to be a solution to this very distinction. And when we begin applying this distinction to the specific claims made by Christian nationalists, the effects of this twisting of theology become clear rapidly.

Let’s take an example. Dr. Wolfe tweeted a few days ago that “Your natural instinct to love and prefer your own is good actually.” Now, I’m planning to discuss the many Scriptural issues with this in my next post, so we’ll set those temporarily aside. We also won’t, for now, question whether there in fact is any “natural instinct to love and prefer your own,” nor insist that even if there is one, it really should have been defined for the sake of a statement like this. And we will certainly not make any cheap jokes about the look that would appear on John Calvin’s face if you claimed to be a disciple of his theology and then said, without qualification, something that even sounded like Your natural self-love is a positive good, no matter how funny and called-for the face might be.

This seems like the kind of vibe Calvin would give off in person, right

It would be wrong to argue that things like loving your country or your family or your home town are bad. You might love any of them excessively, sure, but that’s a different problem (sort of like the problem with having a fever is not that you have body heat). There is even room in Christian theology, especially Catholic theology, for the claim that “preferring your own” is innocent in itself, insofar as it means looking after their needs and desires. The thing is, all that truly does is establish an order of priorities. What it doesn’t do—which Christian nationalists clearly wish it did and try hard to imply it does—is give you the right to look after your own and ignore everyone else’s. To say “the love of X is good” does not in any way prove that the hatred of Y is guiltless, or inevitable, or trivial. Scripture (as we’ll go into later) gets explicit about this, not to say pushy, but even from a purely logical point of view, yes to X does not of itself mean no to Y.

Moreover, there’s a gigantic difference between allowing something as a concession to circumstance, and promoting it as a positive good. A rehab doctor who recommends that a junkie be given slowly decreasing doses of heroin while in recovery due to physical dependence, is not saying or even hinting that it’s great to be addicted to opioids! Elisha gave Naaman the Syrian a dispensation for pretending to worship idols (to express the transaction in modern, Catholic terms), but that was quite the rare dispensation, and it has rightly stayed rare. Most of the allowances made by Christianity to our natural love of country and even of family are precisely that: allowances. Exceptions to normal rules that are still in force. The New Testament is quite painfully clear on this; to it let us, therefore, turn.

Footnotes

1To all appearances, that is—I try to take great care not to accuse anyone of lying unless it seems irresponsible to do otherwise. Hence, while I know of no evidence to support these possibilities, I will say that it is strictly possible that Wolfe (a professor at Princeton) somehow became so confused somewhere along the line that he genuinely believes the things he has written on these topics; he may, for example, be stupid, or perhaps he is freshly arrived in this timeline and hails from an alternate in which Achord is a better person.

2This delicate and unpleasant word is in my opinion thrown around far too casually anyway, chiefly by politically conservative Catholics. I won’t go into a full explanation here—the subject calls for a post unto itself—but I will say that what’s known technically as material heresy, or believing ideas that have been condemned by the Church, should be firmly distinguished from formal heresy, or believing such ideas for a blameworthy reason. Plenty of people who are perfectly sincere and open to teaching, but have the bad luck of a poor religious education, authorities who lie to them, etc., may easily become material heretics without being formal heretics at all, and don’t deserve to be tarred with the latter brush.

3Tollit here is a bit tricky to render in satisfying English; the verb tollere is a simple one meaning “to take,” but its secondary senses went in slightly different directions from its English equivalent. “Take away” is a fairly literal translation, but “destroy” or “replace” might be more idiomatic.

4Morgan is the Welsh equivalent of the Latin name Pelagius; as the Pelagius was from Britain (and the Anglo-Saxon settlement-slash-conquest of England had only just begun), he presumably spoke Common Brittonic, the contemporary language ancestral to Welsh, and was likely named Morgan or something similar, but took the Latin name when traveling into Italy. The point is, while I could have made this section’s title “We Need to Talk About Pelagius,” it would throw off the rhythm and thus ruin the allusion to We Need to Talk About Kevin, as well as preventing me from sharing a factoid about Common Brittonic, and I’m not about either of those things.

5That is, we could say this about its original meaning. The term lost a lot of precision over the centuries, and I’m leaving out most of its history. I encourage anyone who wants to know more to purchase a copy of C. S. Lewis’s invaluable book Studies in Words, which has a whole chapter devoted to nature and its derivates.

6For instance, the attitude, and to some extent the defined theology, of Eastern Orthodoxy tends to be milder on the topic than those of Catholicism. Meanwhile some Protestant versions, notably the Reformed doctrine of total depravity, are significantly more stern than the Romish.

7This criterion of relevance is what distinguishes being appropriately precise from pedantry and hairsplitting: these fuss over distinctions that may be factually correct but don’t really affect the argument. Pedantry and splitting hairs are thus a kind of equal and opposite error from equivocation.