The Veiling of the Ikons

The Fifth Sunday in Lent, this past, is also known as Passion Sunday. Falling one week before Palm Sunday, it used to be the beginning of a discrete sub-season within Lent, known as Passiontide. One observance from this period that remains common is the veiling of ikons, crucifixes especially. Purple is the most traditional color for the veils, if I recall correctly (but white and black are also used); it makes me think of something Chesterton said somewhere or other about purple vestments, which are rich like gold or red but darker, as if to convey a sense that a splendor is now in eclipse. The veiling is a sort of visual fast, and an expression of the gravity of the imminent commemorations of Holy Week. Sometimes it is also connected to John 12.36: These things spake Jesus, and departed, and hid himself from them.

We don’t have enough veils at my parish to cover absolutely every image in the church, but all of the crucifixes are covered. So too are the ikon and reliquary of St. Edward the Confessor at the epistle-side1 side altar,2 and the sculpture of Christ the King set in the reredos of the side altar opposite. Even the rood, which here is hung by chains over the steps from the nave up to the sanctuary (we have no rood screen), has a large purple cloth over the corpus, leaving the Virgin and St. John looking oddly isolated on either side.

Jerusalem

Two Gospel passages were in my thoughts over the last couple weeks or so. Both seem to me to have to do with this sense of sudden concealment on God’s part. One came through the medium of the rosary, specifically the Fifth Joyful Mystery. This recounts the Holy Family’s Passover visit to Jerusalem when Jesus was 12, his being mistakenly left behind afterwards, and the Virgin and St. Joseph spending three anguished days searching for him when they realized he wasn’t with them. They found him in the temple, talking shop with local scholars of divinity.3 Naturally she scolded him: Son, why hast thou thus dealt with us? thy father and I have sought thee sorrowing.

I’ve long wondered why this little incident is the Fifth Joyful Mystery, rather than the Epiphany, which has a much more obvious theological significance (its full title is after all “the epiphany of the Lord to the Gentiles“), not to mention a greater penumbra of splendor with its gold and incense. Several years ago I read Fr. Reginald Garrigou-Lagrange’s The Three Conversions in the Spiritual Life, which describes the dark night of the soul4 at some length, and was surprised to find that he associated the dark night not with her vigil by the Cross, but with the loss of Jesus in Jerusalem, leading up to this episode. Actually, “surprised” is less than the truth: I thought it seemed forced, even artificial.

Then one day—I don’t know why—the words of Mary on finding Jesus there suddenly came to my mind beside the most famous of the seven words.

Son, why hast thou thus dealt with us? behold, thy father and I have sought thee sorrowing.

†††

My God, my God, why hast thou forsaken me?

I seriously doubt I’ve unpacked the connection here; nor do I think I’m likely to in the time between writing this down and hitting “publish.” But I definitely feel like there’s something here.

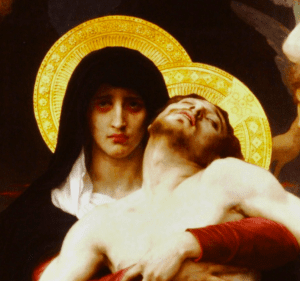

As with Jesus, so too with Mary, I think that in the midst of contemplating the graces and honors she received, many of them unique, we’re apt to forget that she was (in most respects) an ordinary first-century Jewish woman. In a town not even seedy enough to be a “wretched hive of scum and villainy,” little more than the butt of local jokes, there lived a peasant girl of no great distinction who whiled away her time doing her household chores; to her were these graces and honors given.

A Short Lectio Divina Exercise

Try and put yourself in her shoes. After the first two or three extremely dramatic years of your surprise Son’s life, you thought everything was going to be as pleasantly quiet for the rest of his childhood as it was for the first twentyish years of your life.5 Simeon’s prophecy about a sword through your heart—well, you heard about the innocents of “Bethlehem and all the coasts thereof,” no doubt, and you spent years in exile immediately thereafter, so that was presumably fulfilled.

And then, just about when Jesus was coming of age,6 during a trip that should have been completely normal, poof, he disappears. Kidnapping?—which, back then, normally meant being sold into slavery, and that could mean vanishing to anywhere; the Torah forbade kidnapping, but people don’t always follow the Torah, not to mention the occupying force of Gentile soldiers! Imprisonment?—possible, if he’d said something he didn’t realize was politically dangerous. Especially something about the family lineage. Roman officials wouldn’t like the threat of unrest, Hasmonean dynasts wouldn’t like a rival claimant to the throne, and elders of the Sanhedrin would be wringing their hands over the frightening implications any violence could have for the temple renovations that weren’t even finished yet. Murder?—well—in a city this size … And so the searching, searching, probably pausing only for food and sleep, racking your brains and your spouse’s to think of where he could possibly be, anything he’d mentioned that might be a clue …

And then, when the two of you retire to the temple, perhaps to make a last-ditch prayer for a miracle: there he is. Perfectly safe, apparently none the worse for wear, having quite a witty conversation with the local scholars about his Torah study; and your darling brat has the nerve to say, “Why didn’t you look for me here first?”

Bethany

The other passage was the reading this past Sunday, which comes from John 11. It recounts the resurrection of Lazarus from the dead. Two things stuck out to me about this passage this past Sunday. One is the implicit reproach7 in first Martha’s and then Mary’s greetings of Jesus: Lord, if thou hadst been here, my brother had not died. We’re so used to hearing this in the context of John 11 that I think it can come off merely as an affirmative confession of his miraculous powers. But again, picture it. You walk into a wake; the sister of the deceased looks up, then looks you right in the face and says, in front of everyone, “If you’d gotten here sooner he would be alive.”

This, to me, reads like a sucker punch. High intensity, for sure, but it is a pretty natural thing to say under the circumstances. The odd part comes from Martha, in verse 21: I know that even now, whatsoever thou wilt ask of God, God will give it thee. Which is weird, because verses 39-40 imply that she didn’t expect a miracle of resurrection. So what is she talking about?

This oddity, I’ve really got no answer for. Guess away. But the passage as a whole did stick out to me in this way: Martha—poor Martha, forever saddled with being the archetype of a suburban hausfrau’s petty piety!—here makes one of the boldest confessions of faith in the Gospels. Jesus opens, as my parish pastor pointed out, with a doctrinal commonplace of Pharisaic Judaism,8 so bland as to be little more than “God has a plan,” a tasteless sort of remark to make to the bereaved at a funeral. Then:

Jesus saith unto her, “Thy brother shall rise again.”

Martha saith unto him, “I know that he shall rise again in the resurrection at the last day.”

Jesus said unto her, “I am the resurrection, and the life: he that believeth in me, though he were dead, yet shall he live: and whosoever liveth and believeth in me shall never die. Believest thou this?”

She saith unto him: “Yea, Lord: I believe that thou art the Christ, the Son of God, which should come into the world.

In other words: her brother has just died; all human experience and textual evidence suggest that she expected him to stay dead; and then, out of nowhere, her favorite preacher says that he is the final resurrection, and without missing a beat, St. Martha tells him, “I believe you.”

What?

Blessed Are They That Have Not Seen

The exact details of what Martha grasped and when are beyond me. I had a striking parallel to set beside the passage from Luke 2; I have nothing to place next to John 11.

What captured my mind about this text was something else. John 11 draws to its climax with the resurrection of Lazarus, and we tend to project this backward onto the way we think about the words and behavior of the non-Jesus characters. For example, this is probably why we so easily think of the apostles (among others) as stupid: we only have to move a few verses down to get from the feeding of the four thousand to the admonition against the “leaven of the Pharisees and of Herod” in Mark 8, but for them, a minimum of a few hours seem to have passed—plenty of time and cause to get distracted, especially when you’re tending to a boat.

The point is, Martha and Mary, though they may have witnessed miracles before now, had not seen the dead brought back to life. So the conditions they were in, and the faith that they had, were … pretty much the same as mine.

I’ve been complaining lately, mostly in relative privacy, about not understanding or being able to make sense of things. I wonder.

Please pray for me. I’m hoping to post my usual “meditations for Holy Week” tomorrow evening, and then to spend the following week off the blog and (if all goes well) getting into the confessional at some point in there.

Footnotes

1As you enter a church, the epistle side will be to the right (unless the door you’re entering through is set at an unusual place or angle), and the gospel side will be to the left. They are not the same as right and left, though; they’re more like starboard and port on a ship: the referents are relative to the ship’s own shape, not to your orientation.

2Many (not all) Catholic churches have small secondary altars placed in the nave, or in small chapels connected to it. These are often dedicated to locally important or popular saints, and in the past were frequently chantries, specially devoted to prayer for the souls of the dead.

3We are not told exactly where in the temple this took place. Near the center lay the Court of the Priests, which Jesus (being a Judahite, not a Levite) would not have been allowed into. Two more courts lay beyond this. Beyond these again was the Court of the Gentiles: as the name implies, anyone could enter it, and it was largely taken up by a bazaar, notorious to us from the four Gospel accounts of the cleansing of the temple. I imagine this would have been too noisy and distracting for battles of wits in interpreting the Torah.

This leaves the two middle spaces: the Court of the Israelites (between that of the Priests and the next one here), where only ritually pure Jewish males were admitted; and the Court of the Women (between that of the Israelites and that of the Gentiles). Of the two, I’d assume theological sparring would take place in the Court of the Israelites, since women were exempted—perhaps excluded—from the study of the Torah. This would mean that the Virgin Mary rushing in here to collect her Son, whether chaperoned by her husband or not, would have been in dramatic defiance of temple protocol. Given the boldness and self-possession she exhibits elsewhere in Scripture (challenging an archangel to explain himself, traveling alone to visit her pregnant cousin, standing right in front of her Son’s public gallows-tree), I find the idea that she did this quite appealing, but I am too ignorant of the actual practices of the Second Temple period to have confidence in my guess.

4This name, drawn from St. John of the Cross, denotes a particular stage of purification in the way of the soul practiced by mystics. It is characterized by a sense of confusion, helplessness, and abandonment by God, despite previous experiences of illumination, confidence, and sweetness from him.

5There is a widespread belief that girls typically married at 14 or even younger in first-century Palestine, and that therefore the Blessed Virgin would have been about this age at the Annunciation. However, this assumption seems to depend on contemporary Roman, and even specifically patrician, customs; 18 was a more normal age for marriage among the Jews, and was recommended by the rabbinic consensus recorded in the Mishnah, compiled not long after the life of Christ.

6The idea may be attractive, but Jesus almost certainly did not have a bar mitzvah. He would (as far as I can tell) have been considered an adult for religious purposes from age 13, just as in modern Judaism; however, the bar mitzvah ceremony does not seem to have developed until the fifth or sixth century.

7I specify “implicit” because I can see at least one other interpretation of this. Only a few verses earlier, Jesus tells the disciples they are returning to Judea proper to visit Lazarus and his sisters; St. Thomas (who may have been a bit of an Eeyore) not only expects this to result in Jesus being assassinated, but considers it such a foregone conclusion that his idea of a group pep talk is Let us also go, that we may die with him. In that light, I think it’s possible that the sisters were saying, not “You could have fixed this; how dare you delay?”, but something like “You could have fixed this; if only they’d have let you come near him.”

8The fact that the word Pharisee became, in Christian parlance, a synonym for hypocrite is unfortunate for several reasons (not least the way it smoothed the path for Christian anti-Semitism). But one of these reasons is, it obscures the fact that Jesus and the primitive Church were, quite recognizably and distinctly, Pharisaic in their theology—so much so that St. Paul was able to use the fact to his advantage in a trial before the Sanhedrin (recounted in Acts 23).

Granted, Jesus’ interpretive style and application of the Torah was highly objectionable and heterodox to other Pharisees. But nobody would mistake him for one of the Sadducees, the priestly elite who rejected all Scripture except the Torah, and denied ideas like the existence of angels and the final resurrection; nor for a Zealot, whose response to foreign oppression was to organize patriotic revolt. Nor could he be mistaken for an Essene, not really—under their influence, maybe, but not one of them, with his clear endorsement of the temple, his very public ministry, and his curiously generous attitude toward Gentiles. All his theology aligned him with the Pharisees; and, if there were any doubt, even as damning a passage as the Seven Woes of Matthew 23 goes out of its way to open with the affirmation that the scribes and the Pharisees sit in Moses’ seat: all therefore whatsoever they bid you observe, that observe and do.