(Those who read Roman numerals easily may have spotted that the Arabic and Roman numerals in the title are misaligned, and can’t I count? The answer is: yes, but the liturgical year changed on 3 December. See my post on the Feast of St. Andrew for further details.)

The Moment of the Rose

This coming Sunday will be the Third Sunday of Advent, known as Gaudete, or Rose, Sunday. The name comes from the text of Philippians 4.4, which forms the beginning of the introit for this Sunday’s Mass: Gaudete in Domino semper; iterum dico, gaudete; “Rejoice in the Lord always; again I say, rejoice.”

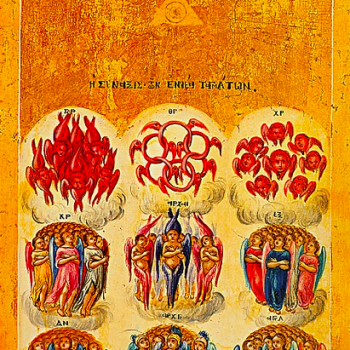

You may know already that there is another Rose Sunday, the Fourth Sunday in Lent, or Lætare Sunday (lætare means “to be glad”). Both take place during the penitential seasons of Advent and Lent. The vestments used throughout these seasons in the Roman rite are normally purple; this is meant to evoke the purple robe in which Christ was arrayed to be mocked by the soldiers during the Passion. Rose vestments are allowed for Gaudete and Lætare Sundays partly because these roughly mark the halfway points of each season. The idea is that rose represents a relief of the rich darkness of purple, a brief glimpse of the light that is approaching.

A conventional Advent wreath, with three purple candles

and one rose (the white Christ candle is often left out

until Christmas Day, when it is lit for the first time).

This meaning is especially well-suited to Advent, a season focused on the symbolism of light. Several of the saints we commemorate in December are tied into the imagery of light in one way or another, and in fact this week has three in a row. First there is the feast of Our Lady of Guadalupe on 12 December: in her image on the tilma,1 her blue-green mantle is decorated with golden stars, evoking the imagery of Revelation 12.1.

The following day is the memorial of St. Lucy, a consecrated virgin from Syracuse in Sicily. Lucy is one of the saints from the Roman canon—you know the bit; the one that goes Felicity Perpetua Agatha Lucy Agnes Cecilia Anastasia Andofallthysaints? Like most of the women in that list, St. Lucy was martyred in the Diocletianic Persecution of 303-311. Her name, Lucia (the feminine form of the Roman name Lucius), means “light”; she is a patron saint for people with weak eyesight, and features in the Divine Comedy as a symbol of illuminating grace. Lucy was long a key saint in the Advent season, not unlike St. Andrew himself, if perhaps for practical rather than devotional reasons; however, since the Ember days were dropped,2 St. Lucy’s day has lost something of its importance.

Finally, on the fourteenth, we have St. John of the Cross, one of the two great founders of the Discalced Carmelites.3 His alignment with Advent is a little paradoxical—which, incidentally, is perfect for Advent. Please allow me, in explaining why, a short and yet unnecessary detour of around four hundred years and a mere eighteen hundred kilometers.

Flyte in Fatigues

Dana Gioia and Eve Tushnet have covered Dunstan Thompson better than I can. The short version is, he was one of our boys in the European theater during World War II, and after the armistice, as a gay boy will, he both fell in love with an Englishman and rediscovered his Catholic faith. He and the Englishman made a home together in the east of England for about thirty years, until Thompson’s death. His poetry, which before then had been tortured, confessional stuff thick with veiled homoeroticism, became much more tranquil and “classical” in both form and matter, rather reminiscent of fellow expatriate T. S. Eliot. Take the dark flourish and assertively anatomical quality of this stanza from one of his first poems, “Lament for the Sleepwalker”:

See, like a rajah, how he ravens fine food.

The long claws fork their lightning; diamond, his teeth,

Glitter of jewel jaws, dazzle—glaze their mirrors

Black blood and purple, stained points of glass. Beneath

Lascivious fur, his regal muscles flex,

Digesting fire, the marrow root of sex.

And now compare this with a stanza from “The Moment of the Rose,” one of his later poems, written after the war and his reversion to his childhood faith. (I’m especially struck by a sensation that air and light have taken the place that before was clotted black with blood.)

The end of love is that the heart is still

As the rose no wind distresses, still as light

On the unmoved grass, or as the humming bird

Poised the pure moment by an act of will.

Death may be like this, but here before night

Send us to sleep murmuring a drowsy word

Of prayer, affection, or the idle flight

Of fancy, let us praise the rose and light.

Dunstan Thompson was not a mystic (or if he was, he did a good job of keeping it quiet); he is not an English version of St. John of the Cross, or anything like that. But he shared certain interests and traits with the great Spanish Carmelite—not least, a certain hard-headed common sense, expressed by the Englishman in “The Halfway House”:

This ordered life is not for everyone.

Never, to their surprise, for those who run

Away from love. …

You see, we are not playroom monks. Our hearts

Are in this, or we go. If not, the starts

And stops tell all the others what we ought

To do, and they persuade us. Had you thought

We stayed because we liked the quiet at night?

One feels that could sit pretty comfortably in the early chapters of The Dark Night of the Soul, where St. John discusses the spiritual forms taken by the capital sins in the lives of beginners.

“Dark With Excessive Bright Thy Skirts Appear”

That famous title, The Dark Night of the Soul—it fits into a larger theory of the spiritual life put forth by its author. That theory need not detain us in full, but one of its important details is that the “dark night” for which the book is named is not, from the heavenly perspective, darkness at all: not because God is all-knowing, but because what is (metaphorically) happening to a soul in the “dark night” is that they are being dazzled. They have emerged from a cavern with scanty, terrestrial light, of a kind they were used to, into the blazing noonday sun of celestial wisdom. Of course their vision fails for a while.

This is not the same pattern as Christ humbling himself in the flesh, ultimately submitting to the Passion and obtaining the Resurrection. It think it’s more that the two concepts rhyme with one another; both express something, a volta not unlike Tolkien’s explanation of eucatastrophe. Speaking of whom, the salutation of Eärendil4 in the final chapter of The Silmarillion is one of my favorite examples of this. Perhaps I could resist the urge to quote it; however, I don’t want to:

Hail Eärendil, of mariners most renowned, the looked for that cometh at unawares, the longed for that cometh beyond hope! Hail Eärendil, bearer of light before the Sun and Moon! Splendor of the Children of Earth, star in the darkness, jewel in the sunset, radiant in the morning!

“The looked for that cometh at unawares”; I love that phrase. (Among other things, very apt for Christmas.)

Speaking of voltas, the life of St. John of the Cross seems to have been composed from an unusually high proportion of abrupt turnings and even disasters. John—like St. Teresa, the other and elder founding figure of the Discalced—was a child of conversos; that is, Spanish Jews who had converted to Catholicism5 rather than be expelled from Spain after the cruel Alhambra Decree of 1492, and who continued to be monitored by the Spanish Inquisition and restricted in rights by the Spanish crown. To my mind, a less-likely environment in which to foster sincere love of Christ and obedience to the Church is almost impossible to imagine!

And his order treated him far worse than his country already had. The Discalced branch was quite unpopular with a great many Carmelites, despite already having the formal approval of the Church. At one point, St. John was kidnapped—actually kidnapped—and imprisoned in a cell in a convent belonging to the “calced,” who subjected him to public lashings, refused to give him a lamp even to read his breviary6 by, and fed him scraps. He endured this treatment for eight months.

Eventually he escaped, on the Solemnity of the Assumption. Yet it was not then, but while he had been locked up, hungry, humiliated, and beaten, that he composed some of his most celebrated mystical poetry, all about the unspeakable sweetness of intimacy with God.

Anonymous portrait (attributed to Francisco de Zurbarán) of St. John of the Cross,

1656. The saint died in 1591, so it is possible—though entirely conjectural—

that the painter consulted living people who remembered what he looked like.

O Night, thou wast my guide!

O Night more loving than the rising sun!

O Night that joined the Lover to the Beloved one,

Transforming each of them into the other.

And what else is the imagery of Advent? As the days come to their very shortest, we proclaim that the light is nearer; we “anticipate” a birth that happened thousands of years ago; we “commemorate” the union of time with eternity.

Footnotes

1A tilma was a kind of cloak worn in Mexico (I understand that both the word and the garment originate in Aztec civilization). The tilma in question belonged to St. Juan Diego; according to some accounts of the apparition, the image of Our Lady of Guadalupe on his tilma, which now hangs in the Guadalupe Basilica and is the basis for depictions of the Guadalupana generally, appeared there miraculously as a sign to Juan Diego and his bishop.

2The Ember days were the Wednesday, Friday, and Saturday of four weeks of the year, roughly corresponding to the beginnings of the meteorological seasons; they were set aside for abstention from meat, light fasting, prayer (especially for the clergy), and ordinations. The spring Ember week was the first (full) week of Lent; the summer, the Octave of Pentecost; the autumn, the week following 14 September; and the winter, the third week of Advent, which always falls after St. Lucy’s day, 13 December.

3The Carmelites are a small family of religious orders and houses, certainly in existence by no later than the end of the twelfth century, and possibly in existence earlier. In the sixteenth century, a nun named Teresa Sánchez wanted to found a reformed branch that practiced greater austerity; this branch became known as the Discalced Carmelites (from a Latin word meaning “barefoot,” indicating their extreme poverty). Teresa, the foundress, was eventually canonized; most people know her as of Ávila, though her name in religion was Teresa of Jesus.

4Eärendil was a hero of Middle-earth in the First Age, so rather more than six thousand years before the lives of Bilbo and Frodo; he was one of the Half-Elven, and in fact was Elrond’s father. He was renowned for sailing to Aman, the realm of the Valar (the “lower-case ‘g’ gods”: benevolent, powerful, and wise, but neither omnipotent nor all-knowing), and winning mercy for the Elves in exile and their Mannish allies. Both kindreds had been devastated in a centuries-long war against Morgoth, a corrupt former member of the Valar—indeed, originally the most powerful Vala—who had stolen the Silmarils, three magical gems that preserved the holy Light which had existed “before the Sun and Moon” were made. One Silmaril had been stolen back by the Elvish princess Lúthien and the Mannish hero Beren, who were the grandmother and grandfather of Eärendil’s wife Elwing (so that Elwing was also Half-Elven). When she brought the holy jewel to her husband’s ship, its light pierced through the enchantments that turned ships away from Aman. When Eärendil first landed, the place seemed empty; the quoted lines were the first words spoken to him in Aman, by Eönwë, the herald of the Valar.

5Some of these Jews continued to practice Judaism in secret—sometimes for many generations.

6A breviary is a book containing the Liturgy of the Hours, the daily prayer of the Catholic Church, consisting principally in psalms and other passages of Scripture. Monastics are bound by canon law to recite the Hours (also known as the Office, from the Latin officium “duty”) every day; the mainstream Carmelites here forced him to use a small, fickle patch of light that filtered into his cell to read his breviary, which would teach him to have the audacity to … not try to impose the Discalced reform on any Carmelite house except the ones who specifically requested it.