When Were We?

This question is relevant to two things: the liturgical date, i.e. the second Sunday after Epiphany; and the Gospel text itself, which picks up from the same sequence as the Johannine readings of Advent.

First, some readers may be a little confused that this is the second Sunday after Epiphany (or, in the mainstream Roman rite, the second Sunday in Ordinary Time), given that last Sunday was Epiphany. However, if I’ve understood the rules correctly—which, heh, is not certain—this is how the numbering works because this is the Sunday after the Feast of the Baptism of Christ, which normally falls on the first Sunday after Epiphany. However, if Epiphany is transferred to the nearest convenient Sunday (as is the normal practice in the US), it will occasionally fall on 7 or 8 January, which fall after the solemnity’s “native” date; when that happens, the Baptism is instead celebrated on the immediately following Monday. I gather that this is done to keep the Baptism from falling any closer to Ash Wednesday, but I’m not sure. (We have a relatively early Easter this year, and, while Ash Wednesday is still in February as usual, Shrovetide actually begins in January.)

Second, the continuation of John. We last heard from this Gospel on Gaudete Sunday, when a delegation from the Pharisees came to cross-examine St. John the Baptist on his theology. The Baptist, while saying flatly that he was not the Christ or the return of Elijah, did identify himself as “the voice of him that crieth in the wilderness, ‘Prepare ye the way of the Lord.'” In that post—which I encourage you to go back and read, if you haven’t already—I also discussed three important motifs in the Gospel of John: the imagery of court proceedings (look for language about witnesses, testimony, and judgment), the figure of the Baptist, and something of the nature of the Pharisees. The first and third of these motifs are less immediately relevant to this passage, but all are worth bearing in mind throughout the Gospel of John.

John 1.35-42, RSV-CE

The next day1 again John was standing with two of his disciples2; and he looked at Jesus as he walked, and said, “Behold, the Lamb of God!” The two disciples heard him say this, and they followed Jesus. Jesus turned, and saw them following, and said to them, “What do you seek?” And they said to him, “Rabbi” (which means Teacher), “where are you staying?” He said to them, “Come and see.”3 They came and saw where he was staying; and they stayed with him that day, for it was about the tenth hour.4 One of the two who heard John speak, and followed him, was Andrew, Simon Peter’s brother. He first found5 his brother Simon, and said to him, “We have found the Messiah” (which means Christ).6 He brought him to Jesus. Jesus looked at him, and said, “So you are Simon the son of John?7 You shall be called Cephas” (which means Peter).8

John 1.35-42, my translation

On the day following,1 John stood with two of his students,2 and, spotting Jesus walking by, he said, “See, the Lamb of God.” And the two students heard his speech and followed Jesus. Turning, Jesus then saw them following and said to them: “What are you looking for?” They said to him, “Rabbi” (which, translated, says Teacher), “where are you staying?” He said to them: “Come and see.”3 Then they came and saw where he was staying, and stayed with him that day, as it was the tenth hour.4

Andrew, Simon the Rock’s brother, was one of these two who had listened to John and followed him; and he first found5 his own brother, Simon, and said to him: “We have found the Mešichah” (which is translated Anointed).6 He led him to Jesus. Spotting him, Jesus said, “You are Simon the son of John7; you will be called Keipha” (which is interpreted Rock).8

Numeric Notes

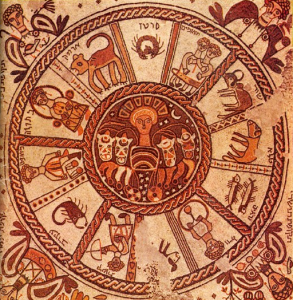

Floor mosaic (6th c.) depicting the zodiac, from

the Beth Alpha synagogue in the Jezreel Valley

in Galilee (southeast of Nazareth); the central figure

is a personification of the Sun, as shown by

his rayed crown and four-horsed chariot.

1: The next day/the day following. Another recurring image in John is that of the creation. Sometimes, as in 5.19-29, this leans in an apocalyptic direction, drawing on material like Ezekiel’s valley of dry bones; at other times, like the prologue (1.1-18), it evokes the language of Genesis 1-2. Now, this allusion to “the day following” fits into a larger pattern in chapters 1 and 2 of John. The first reference of this type comes in 1.29, which mentions “the next day” and therefore establishes two days in sequence: one on which the Baptist’s exchange with the Pharisees took place (1.19-28), and the day following, on which the Baptist first identified Jesus as this “Lamb of God” (1.29-34). This makes today’s passage the third day in the sequence; verse 43 will introduce a fourth.

Why is this important? Because chapter 2 tells us that its events take place “On the third day”: four plus three makes seven, meaning that we now have not only one of John’s all-time favorite things to do (put the number seven in things) taken care of, but have also evoked the symbolism of creation twice over, as Genesis does. Genesis and John both start with God, “in the beginning”. Genesis 1 then proceeds to give the seven-day account of creation, followed by the alternative account of creation in 2.4-25, which lays a far greater emphasis on the making and naming of “Woman.” Likewise, John gives us a rundown of seven carefully specified days, and then, on the seventh, he both gives us a miracle taking place at a wedding, and also features the Logos-made-flesh addressing his Mother—how? As “Woman.” Matthew presents Jesus as a new Moses, born of a new Miriam (Maria or Mariam being the normal Greek forms of Miriam’s name); John presents Jesus and Mary as a new Adam and a new Eve.

An eighteenth-century scroll of the Book

of Esther made in Seville, Spain

2: disciples/students. This is a fairly small point; my preference for students over disciples is an application of my more general principle that translations should ideally be literal as long as literalism serves, rather than interfering with, the meaning of the text. Disciple is not really a word we use outside the religious register any more, and certainly not a synonym for students in general; but, in Koine Greek, the disciples of a rabbi were his “students” in much the same way that people attending Plato’s Academy in Athens were “students.”

A secondary question is just who these two disciples were. We learn in the verses immediately following that one of them was St. Andrew, who then goes to fetch his brother Simon as the third; judging from the rest of chapter 1, the other cannot have been St. Philip or “Nathanael,” known by that name only in this Gospel but generally identified with St. Bartholomew. Curiously enough, aside from Judas Iscariot, the only other members of the Twelve identified by name in John are St. Thomas and St. Jude; the only other member of the Twelve who gets an identity at all, in fact, is “the disciple whom Jesus loved,” traditionally held to be St. John.* Given the author’s concern with immediate, sensory witness (and see note 3 for more on that topic), my guess is that the other unnamed disciple in this passage is the Beloved Disciple, and I do subscribe to the belief that this is the same person as John the Apostle.

3: Come and see. This phrase is intriguing for two reasons. One is that, like several other things in the Fourth Gospel (such as the preoccupation with the number seven), this has an echo in the book of Revelation—or at least, it may. In Revelation 5, a “book” or “scroll” is shown in the hand of God, presumably with some great promise concealed inside; but no one “was able to open the book, neither to look thereon.” It is only when the Lion of Judah is discovered that someone can at last break the seals; and this “Lion of Judah,” when the seer looks at him, appears in the form of “a Lamb as it had been slain, having seven horns and seven eyes.”** In the next chapter, as the Lamb breaks each of the first four seals upon the scroll, each of the four horsemen of the apocalypse appear, in response to a summons from each of the “four living creatures.”† Now, manuscripts of Revelation don’t all agree here, and I understand that the general academic consensus nowadays is that the original and more correct reading is the simpler one, in which the summons is simply “Come”; however, in some versions of the text, the four living creatures in turn instead call out: “Come and see.” Now, even if this reading is correct, I have no idea what this alignment of wording would mean—maybe nothing. But I find it striking, and it would appear to line up with certain other elements in Revelation that present terrestrial persons and events as having cosmological significance.

The other reason this invitation is conspicuous is that it sets up yet another common motif in John, and it happens to be one of the ways in which John is not consistent with the Synoptics. I’m not sure what to make of the inconsistency; probably it’s at least partly a reflection of Jesus making different kinds of appeals to differently-minded students, like most teachers would. Regardless, this “Come and see” has an almost empiricist air to it. The Johannine corpus is very sense-oriented—think of I John 1’s opening: That … which we have heard, which we have seen with our eyes, which we have looked upon, and our hands have handled, of the Word of life; (for the life was manifested, and we have seen it, and bear witness, and shew unto you that eternal life, which … was manifested unto us;) that which we have seen and heard declare we unto you. Most strikingly, it is in John alone that Jesus seems to speak approvingly, or even with any real hope, about faith based on miracles. In the Synoptics, he seems to be almost disgusted by requests for “a sign,” but there is no trace of this in John, where he urges the Twelve during the Upper Room discourse to Believe me that I am in the Father and the Father in me: or else believe me for the very works’ sake (14.11).

Why would that come in here? I am not at all sure; I have a guess, but I do emphasize that it is only a guess. At this very first moment in which he has disciples, they are following him based on the say-so of St. John the Baptist. That isn’t in any sense bad or inappropriate—quite the contrary—but it is different from following him based on knowing him. That can only come later. So maybe, at this earliest stage, he is making a symbolic point of not asking them to take anything on trust too early—not even so much as where he is staying.

Temperance bearing an hourglass. Detail from

Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s Allegory of Good

Government, 1338.

4: the tenth hour. I.e., very roughly, 4 p.m. I cannot now recall where I came upon this idea—I feel like it was in one of Scott Hahn’s books?—but I read somewhere or other that this mention of the time suggests that this exchange took place on a Friday. The notion was that the sabbath rest, with its concomitant restrictions on movement, must be upon them, meaning that they needed to both find a place to stay and get there pretty promptly.

Whether that is true or not, I’m struck by the specification because it fits into John’s constant imagery of light and day. Here, the first two disciples begin to follow him in the last few hours of daylight. In chapter 3, Nicodemus, who does not yet really understand Christ’s importance, comes to him—at night. In the chapter following, it is the sixth hour (noon) when Christ speaks to the “woman at the well” in Sychar. The five thousand are fed in chapter 6, and most of the rest of that chapter is taken up by the Bread of Life Discourse, but this does not actually begin until night has again intervened, a darkness falling between the miracle (6.1-15) and its meaning (6.25-65). The Light of the World Discourse follows not long afterwards, in chapter 8, and then chapter 9 brings us to the healing of the man born blind—after the ominous statement in 9.4 that the night cometh when no man can work. In chapter 11, which revolves around the resurrection of Lazarus, sleep, darkness, night, and death all become almost a single thing. In chapter 12, we pass from the signs that occupy the first half of the gospel, through the triumphal entry, to 12.36, a warning reminiscent of 9.4: “While ye have the light, believe in the light, that ye may be the children of light.” These things spake Jesus, and departed, and did hide himself from them. And then, at last, after the night of Nicodemus who did not manage to understand, and the night of the five thousand who did not try to understand, we come to the night of Judas, who did not want to understand:

Jesus answered, “He it is to whom I shall give a sop, when I have dipped it.” And when he had dipped the sop, he gave it to Judas Iscariot the son of Simon. And after the sop, Satan entered into him. Then said Jesus unto him, “That thou doest, do quickly.” … He then having received the sop, went immediately out: and it was night. —John 13.26-27, 30

An ikon depicting Judas leaving the Last Supper.

What significance the tenth hour might have in light of this, I’m not sure. But the more I read John, the less ready I am to believe there is a single detail in it that made it there by accident.

5: first found. As I mentioned in my post about St. Andrew last year, here again John introduces someone in a significant way. Andrew, every time we see him in John, is bringing somebody else to meet Jesus.

At first, I was disposed to contrast this text with passages like Luke 9.59-62:

And he said unto another, “Follow me.” But he said, “Lord, suffer me first to go and bury my father.” Jesus said unto him, “Let the dead bury their dead: but go thou and preach the kingdom of God.” And another also said, “Lord, I will follow thee; but let me first go bid them farewell, which are at home at my house.” And Jesus said unto him, “No man, having put his hand to the plough, and looking back, is fit for the kingdom of God.”

How come St. Andrew gets to go grab his brother but everybody else gets yelled at? Now, first of all, it might do us no harm to ask whether we have measured up to the virtues of St. Andrew, Apostle and Martyr, before we start complaining that he’s getting better treatment than we are. But, for any worthy servants who have done more than they were commanded, it also bears saying: the guys in Luke here weren’t going to share Jesus with their families. They were saying “I’ll be right there, after this other thing.” That kind of dawdling on the Way is quite different from inviting others onto it. If Peter had refused to accompany Andrew for some reason, Andrew might have come back empty-handed, so to speak; but there’s no suggestion he would have done anything but come back empty-handed.

6: the Messiah, which means Christ/the Mešichah, which is translated Anointed. The English word Messiah comes, through Latin and Greek, from the Aramaic Mešichah [ܡܫܝܚܐ], itself taken from the Hebrew Mashiyakh [מָשִׁיחַ]. (For passages like this one that do allude to Aramaic terms, I’ve decided to try and find the Aramaic whenever possible and transliterate that into English in my version—again, trying to reproduce the feel of the text, and the Greek readers of the Greek original were getting the Aramaic through only one filter, that of Greek phonetics, so I’m trying to filter the Aramaic only through English phonetics and not put them through Greek first.) These words, like the Greek Christos [Χριστός], mean “anointed, anointed one,” the customary term for the Davidic kings of Judah; anointing with oil designated the monarch as God’s deputy in Israel (symbolism probably borrowed from Egyptian culture, where ministers of the Pharaoh were likewise anointed). The modern meanings of “Messiah” and “messianism” come principally from the Christian interpretation of “the Lord’s Anointed” as a savior; while this notion is not alien to the Hebrew Bible exactly, the role of the Mešichah was differently conceived, centered more on being the champion of Judah’s cause than an atoner for Judah’s sins.

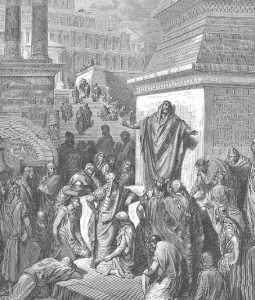

Jonah Preaching to the Ninevites. Gustave Doré, 1866.

7: John. Many manuscripts have Jonah here instead of John; the names are similar in Greek as well as in English (Iōnas [Ἰωνᾶς] versus Iōannēs [Ἰωάννης]). I’m not sure, but I think “Jonah” is probably the stronger reading here. Either name would be easy to erroneously put down in place of the other, but, since the name John is shared by several figures in the New Testament while the name Jonah is only rarely referred to, mistakenly writing John instead seems like the more natural error (because leveling differences by analogy seems more common than thoughtlessly introducing new differences). I will admit, though, that I may be unduly charmed by the literary possibilities here: Peter’s own artisanal character blend of devotee and disaster makes the idea that he was a “bar Jonah” rather attractive; Jonah is one of the funniest and most poignant books in the Hebrew Bible, and his incredibly melodramatic stances (like telling the Lord his God that it’s totally reasonable to be so mad he could die because God let a gourd he liked wither) match St. Peter’s impetuosity wonderfully.

8: Cephas, which means Peter/Keipha, which is interpreted Rock. Cephas is the Hellenized-then-Latinized form; the Aramaic is Keypha’ [כֵּיפָא], or, in the form it took in Classical Syriac (the prestige form of Aramaic, used from about the first century until about the thirteenth), Kēpā [ܟܐܦܐ]. “Rocky” would be a more natural form for this nickname in English, though I’m leery of using it in a translation due to its pop culture associations.

Footnotes

*The Gospel of John never directly identifies either James, the other Simon, or Matthew. This is somewhat surprising, especially in the case of St. James the Greater, who was St. John’s own elder brother. However, the scholarly consensus (which, for once, I don’t see reason to contest!) is that John is the latest of the four canonical gospels, and as likely as not had some knowledge of them; it’s quite possible he had read one or more of them. If so, it would be natural not to retread old ground and instead concentrate on things that had received less attention thus far—which would in fact explain a great deal about the structure and contents of the Fourth Gospel. Of course, as the canny reader may have noticed already, subtracting Judas Iscariot and the four unnamed members of the Twelve from their total gives us seven apostles in John—of which three have some strangeness about their names: the “Beloved Disciple” is never named outright at all; “Nathanael” is given a name never used elsewhere in the New Testament; and, in this very text, the leader of the apostolic college is renamed by Christ himself. (It is curious that this occurs in a moment quite dissociated from its Synoptic trappings, i.e. the episode at Cæsarea Philippi and the Transfiguration. I’m not sure what to make of this.)

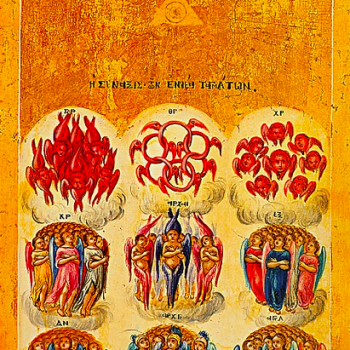

**Seven is a number strongly associated with angels in Scripture: Tobit 12.15 alludes to “seven holy angels … which go in and out before the glory of the Holy One,” and Revelation itself opens with greetings not only from God the Father and Christ, but from “the seven spirits which are before his throne”. That the Lamb has seven horns (a symbol of strength and power in the Hebrew Bible) and seven eyes (symbols of knowledge) thus suggests, among other interpretations, that the Lamb is in some sense the owner or commander of these seven Angels of the Presence. (Whether the Angels of the Presence are Archangels, Seraphim, or something else again—or for that matter, whether they must all be of the same choir—I don’t know.)

†In Christian angelology, the “four living creatures” are generally understood to be Cherubim, members of the second-highest of the nine choirs. (The most typical theory delineates the choirs as follows from highest to lowest: Seraphim; Cherubim; Thrones; Dominations; Virtues; Powers; Principalities; Archangels; Angels.) Additionally, the animate faces of the “living creatures,” i.e. man, lion, ox, and eagle, have become the emblems of the four canonical evangelists.