A Truncation

Our Gospel for the Vigil tonight is to be Mark 16.1-7, which describes some of the women who followed Jesus coming to the tomb on the day after the sabbath, intending to finish embalming the body. However, when they arrived, the tomb was open and Jesus was not in it. What was there was an angel, who told them Jesus was alive, and to go and tell the other disciples to return to the Galilee and meet him there. According to verse 8, the women fled, scared out of their wits. Fin.

Despite the brevity of the passage, the amount of side material that came up ultimately prompted me to divide this post in two! I’m planning to finish the second and post it tomorrow, though I probably shouldn’t be writing that “out loud.”

Photonegative of a portion of the Shroud

of Turin (taken by Secondo Pia in 1898),

purported to be the burial cloth of Jesus

and here apparently showing his face.

This is a very curious Gospel passage for Easter, as is the selection from John read in the morning: neither one features the whole “Jesus alive again” thing that Easter is justly famous for. Did the evangelist forget that bit?

Actually, the close of Mark is a puzzle in general. There are not one but two “let’s round this out, shall we” endings added to Mark later, by someone else: one brief one, known as the “Shorter Ending,” which is relatively uncommon in manuscripts and consists in a sentence or two; and a longer one, creatively titled the “Longer Ending,” that is fairly common—common enough to have received versification, namely vv. 9-20 of chapter 16. It contains a few details that imply the author knew the Gospel of Luke, including the statement that Jesus had cast seven demons out of St. Mary Magdalene (v. 9), and that he appeared to two disciples on a journey (v. 12), though it says that he did so “in another form.”* However, the Longer Ending is absent from the earliest and best manuscripts (such as Codex Vaticanus and Codex Sinaiticus), and is broadly agreed not to be an authentic part of the Gospel.

Even grammatically, it’s an odd conclusion: the last word of Mark 16.8 is gar [γάρ], “for.” Now, this is not as weird as it would be in English, because gar is what’s called a postpositive particle (i.e., it cannot be the first word in a sentence). Still, it’s a strange construction; off the top of my head, I can’t name a single parallel.

In Illo Tempore Dixit: Quid Dat?

There are a handful of explanations for this. One is that the author of Mark was, for some reason, interrupted before completing his narrative, and never got the opportunity to finish it (maybe, or maybe not, for the same reason). Mark was purportedly written in Rome, in the early 60s as likely as not,** and Christianity was outlawed in the wake of the Great Fire in 64; maybe the author was martyred, or had to flee the city and left his unfinished manuscript behind (either by accident or on purpose). In a similar vein, maybe Mark’s narrative did originally proceed to some Resurrection appearances, but the original ending was misplaced early on; it’s even possible, albeit unlikely, that the Longer Ending itself represents somebody’s attempt to re-copy an ending they had read but could no longer find.

I ran across a different explanation somewhere else. I thought it was in the account Eusebius† gave of St. Clement of Alexandria at first, and that does corroborate the backstory I thought I remembered. However, when I looked it up, the details he gave were about Clement’s assertions on the Gospel of Mark in general and not the ending specifically; upshot is, I’m not sure where the last bit of this theory comes from! But the theory goes like this. Mark originated as, essentially, a lecture series given by St. Peter in Rome, recounting what he had seen with Jesus (and leaving out what he had not), which Mark did his best to retain and copy down. The lectures concluded with the empty tomb, so Mark’s document did the same thing. Granted, it’s a little strange that Peter’s lectures concluded at that point in the account: maybe one of the above reasons also applies to the lecture series; or, maybe Peter’s series was only meant to bring the audience up to the point of the empty tomb, that being the last point at which there were other people than the Apostles themselves to corroborate the story.

It’s also weird that we have a seven-verse text here: not in itself, but in that we could literally finish the book by just adding the next verse. C’mon, Church, it’s not a long verse! One more and we could intone Here endeth the Gospel according to Saint Mark. (I’ve included verse 8, in grey.)

Mark 16.1-7 +8, RSV-CE

And when the sabbath was past, Mary Magdalene,a and Mary the mother of James,b and Salome,c bought spices, so that they might go and anoint him. And very early on the first day of the weekd they went to the tombe when the sun had risen. And they were saying to one another, “Who will roll away the stone for us from the door of the tomb?”f And looking up, they saw that the stone was rolled back; for it was very large. And entering the tomb, they saw a young man sitting on the right side, dressed in a white robe;g and they were amazed. And he said to them, “Do not be amazed; you seek Jesus of Nazareth, who was crucified. He has risen,h he is not here; see the place where they laid him. But go, tell his disciples and Peteri that he is going before you to Galilee; there you will see him, as he told you.”j And they went out and fled from the tomb; for trembling and astonishment had come upon them; and they said nothing to any one, for they were afraid.k

Resurrection of Christ by Hans Memling,

1450; originally one panel of a triptych.

Mark 16.1-7 +8, my translation

Once the sabbath had gone by, Miriam from Magdalaa and Jacob’s Miriamb and Salomec bought spices, in order that they might go anoint him. And very early on the first day of the week,d they came to the monumente at the coming-up of the sun, and were saying to each other: “Who will roll away the rock from the door of the monument for us?”f But, looking up by, they saw that the rock had been rolled away (it was extremely large). And going inside the monument, they saw a young man sitting on the right with a white garment thrown on,g and they were overawed. He said to them, “Do not be overawed: Jesus, you are looking for, the Nazarean who was crucified; he was raised,h he is not here. Look—the place where they put him; but go on and tell his students, and Rocky,i that he is going before you to the Galilee; there you will see him, just as he told you.”j And they went out and fled from the monument, for tremors had them out of their minds; and they told no one nothing, for they were afraid.k

Note on the Myrrh-bearers

This name is used in the Christian East for the women who came to tend Jesus’ body, as soon as the sabbath had lifted and they had an opportunity. Their exact number and identities are unclear from the Gospel texts, though there are a lot of traditions. There were at least four: the two Maries mentioned here, a Salome, and one Joanna, who is called the wife of Chuza in Luke (this Chuza being “the steward of the household”—apparently something like a property manager—for Herod Antipas, the one who had St. John the Baptist executed). It is generally believed that there were several more myrrh-bearers than are explicitly named, including SS. Martha and Mary of Bethany, the sisters of Lazarus. SS. Joseph of Arimathea and Nicodemus, though their contribution was made during the rushed pre-sabbath burial given on Good Friday, are also counted as myrrh-bearers, the only two males to have the title.

Branches of the common myrrh tree, from

which a resin used in incense and perfumes

is derived; note the long spines. This species

grows in Arabia and the Horn of Africa.

The only person all the Evangelists definitely, explicitly name in common is St. Mary Magdalene. However, the Eastern Churches also claim that “Salome” was in truth named Mary Salome, likely because we were otherwise so short of Maries in our New Testament; this often goes with the claim that she was a sister of Jesus’ Mother, and yes, it was normal in that time to give multiple daughters the same name and distinguish them by nicknames, additional names, etc. This gives us three myrrh-bearing Maries performing a memorial—none of whom is St. Mary the Mother of God. Indeed, she is conspicuous by her absence from the final chapter of each Gospel, though present at both the Crucifixion and Pentecost.

The point is, if you’re a bit lost, don’t feel bad! Scholars have been tearing each other apart over questions this trivial for generations, because sometimes, scholarly investment in a topic is in inverse proportion to how much it could ever possibly matter.

Textual Notes

a. Mary Magdalene/Miriam from Magdala: The Greek adaptation of the Aramaic name Maryām, itself derived from the Hebrew name Mir’yam [מִרְיָם], was Maria [Μαρία], accented on the second syllable; this is the form that passed into Latin and has remained unchanged in Spanish and Italian, while becoming Marie in French and in English, under French influence, Mary. I’ve opted for the Hebraizing (though not robustly Hebrew) “Miriam” for the same reasons I’ve done things like use “Jacob” rather than the more traditional James: I feel it brings things a little closer to the text, without either sacrificing an appropriate feeling of “at-home-ness” or presenting readers with visually intimidating names like Yaȝaqobh [יַעֲקֹב]; Mir’yam is obviously less out there to an English-reading audience, but why be inconsistent. Additionally, “Miriam” is the form familiar to most of us as the name of Moses’ sister, so that any resonances between her and the many Maries of the New Testament is preserved.

As to choosing “from Magdala” over “Magdalene,” the RSV translation is the more literal: there is no preposition in the Greek, and it uses an adjective derived from the place-name, not a noun; the Magdalan would be the most literal alternative, if I had a grudge against using the term Magdalene for some reason. (In truth I have quite the opposite! I think it’s a lovely word, and wouldn’t even consider using from Magdala in its place in a liturgical context.) The only reason I chose “from Magdala” instead was that I thought Magdalan, being a neologism, might go unrecognized or be mistaken for some other kind of word; I think I remember confusion a few years ago about whether the name of the TV show “The Mandalorian” was a species or a religion, for example. Point is, I decided to just sacrifice flat-footed literalism this once.

A nineteenth-century reliquary housing

what is purported to be the Magdalene’s

skull (her putative skeleton was found in

a crypt in southern France in 1279).

b. Mary, the mother of James/Jacob’s Miriam: Technically, all this text says is “the Maria of Iakobos,” or “James’s Mary,” which could indicate a mother, a wife, or even a daughter. (It might in theory be used for other female relations as well, but a mother, wife, or daughter would be the likeliest to be identified according to who her son, husband, or father was—not unlike today, though we use the phrase less often.) That’s a bit vague, obviously, and a few more specific identifications have been proposed

There were two different apostles of this name, known as “St. James the Greater” and “St. James the Less” in later tradition; whether the difference between them was in age or literal size, or both, is unknown (at least to me), but neither of them is reputed to have been married. On the other hand, going by the personal favor she requested from their rabbi, “the mother of Zebedee’s sons” was rather a bold personality with a strong investment in her sons’ prestige—it seems natural to think of her as “James[ the Greater]’s Mary,” to my mind!—so that’s a credible possibility.

But there is at least one more, which the “Mary Salome” tradition above makes if anything more plausible, in my opinion. Among the many “background characters” of the New Testament is a Clopas, generally taken to be the same person as Cleopas or Cleophas, one of the two disciples on the road to Emmaus in Luke 24. Now. The other James, St. James the Less, is described in Matthew as “the son of Alphæus.” So what? Well, there was a name in Hebrew, Chalphi [חלפי], that also had an Aramaic adaption, Chilphai [חילפאי], either of which could easily get “heard as” anything from Clopas to Alphæus by a Greek-speaker. If this Chalphi or Chilphai were the father of one of the apostles, it’d make sense to find him involved with the early Church; and if his wife also happened to be named Miriam, then his son Jacob would make her a “James’s Mary.”

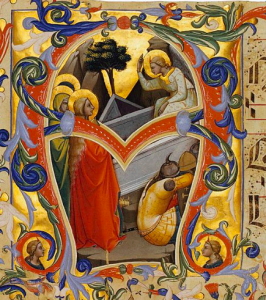

An illuminated capital by Lorenzo Monaco,

from an antiphonary from 1396, depicting

“the Three Maries” at the tomb.

c. Salome: The name Salōmē [Σαλώμη] is generally held to be derived from shalom [שָׁלוֹם], and was very common at the time (at least two members of the Herod family, Herod Antipas’s sister and his stepdaughter, also bore the name). The Judæan‡ form of the name would be Sh’lomit or something similar—the ending –t or –th nearly always denotes the feminine in Semitic languages (Arabic, Aramaic, Egyptian, Hebrew, Punic); think of it as a little like our suffix –ette. This means that Sh’lomit, and by extension Salome, are female cognates of Sh’lomoh [שְׁלֹמֹה], “Solomon.”§

Anyway! For reasons cited in note a, I decided against using Sh’lomit, so, with due background here, “Salome” it is.

d. tomb/monument: The Greek term denotes a grave, and is also related to the verb for remember. “Memorial” would have been an alternative, but I don’t think I’ve seen that used as a word for a grave itself, whereas “monument” is perfectly good English for a tombstone, so I used it here.

Hebrew inscriptions on tombstones in a

town in the Czech Republic. Photographed

by Ladislav Faigl in 2010, used under a

CC BY-SA 3.0 license (source).

e. very early on the first day of the week: The Greek words “very early” here, lian prōi [λίαν πρωῒ], seem to be a pair that Mark really likes, sort of like his constant usage of euthüs [εὐθὺς]. Compare how in Mark 1.35, Jesus gets up prōi ennücha lian [πρωῒ ἔννυχα λίαν], “very first thing in the dark of the morning,” or even more literally “first in-dark, very”.

“On the first day of the week” is a little more idiomatic than I’d like, but I couldn’t think of a really equivalent idiom in English. Flat-footedly it comes to “on the first [f.] of the sabbaths”; in Greek, the word for day is feminine, and sabbath was occasionally used to denote the seven-day week (there were other equivalents of a week in the Roman world that had different numbers of days), so the translation is clearly correct; it just leaves me crabby that I can’t get it neatly into the translation “algorithm” I want.

f. “Who will roll away the stone for us from the door of the tomb?”/”Who will roll away the rock from the door of the monument for us?”: This might seem like a very Why didn’t you plan this better? kind of question. There are a few possible explanations. One is that it was quite simply one of those failures of memory that does occasionally happen, even in group planning. Another is that, since the verb here is an imperfect (“were saying to each other”), and the imperfect can indicate a repeated or ongoing discussion, Mark is here telling us the topic of their conversation on the way there, rather than saying they hadn’t raised the question until then. This is my personal opinion. However, I spent some time thinking out a third idea, before the uses of the imperfect struck me as a simpler answer, and I still think it may have some merit.

This third idea is that they expected someone else to be there too, a person or a group of people who could have opened the tomb for them, but that this party was conspicuous by their absence at a glance, even before the equally-if-not-more alarming absence of the boulder was completely clear. The obvious candidates would be the contingent of Roman soldiers assigned to guard it: a group of soldiers could certainly move the boulder, and their absence (after being placed there by the Sanhedrin to prevent funny business) instantly noticeable, even in the low light of dawn.

Roman legionary reënactors, based on

armor, etc. in use in the first to third

centuries. Used under a CC BY-SA

3.0 license (source).

Now, the obvious objection to this is that the Romans had just executed Jesus, so for the women to plan on the sympathy of the guards is hopelessly far-fetched. However, I’m not so sure it is. Neither Pilate nor, presumably, the guards had borne any special malice toward Jesus—he was another Jewish weirdo with a Jewish weirdo religion and Jewish weirdo friends, who cares; but it does not do to risk the unfavorable attention of Tiberius Cæsar or the people who work for him, so whatever, execute the weirdo. But you don’t need to be a jerk to his family and friends after that: you went with the execution to honor orders or to avoid a beating or to not get accused of conspiring with Sejanus, not in order to be a dick to the locals for the sake of it. (As a matter of fact, you’d probably been ordered broadly to avoid that, given how touchy these provincials were about their aforesaid weirdo religion. The last thing your commanding officer wanted to deal with was an uprising, and the next-to-last was a riot.)

Moreover, tenderness toward the supplications of people mourning their dead is one of the oldest, most reverend feelings in human society (the very Iliad closes with Achilles consenting to return the body of his enemy Hector to his father). The Romans were peculiarly insistent on due propriety being observed for the dead, even sometimes the disgraced dead. Therefore, it might be surprising, but it would by no means be shocking, if the guards let the women into the tomb to finish embalming the body. From the Sanhedrin’s perspective, to do so would even have the advantage of furnishing more eyewitnesses of any attempt to steal it.

Notes g through k coming up: in other words, TO BE CONTINUED …

*This seems to reflect the statement in Luke that, when Jesus appeared to the disciples heading for Emmaus, “their eyes were restrained” so that they did not recognize him. It has not been well-liked by the orthodox, as it could easily be interpreted as docetist; whether the author (whoever it was) intended it that way is hard to say.

**It used to be fashionable among manuscript critics to date the composition of all four canonical Gospels as late as the late second century. We don’t do that now! But there is still controversy over whether each one belongs to the mid-first century, and thus to the first and maybe second generation of Christians, or the late first century, ascribing them to the second, third, and fourth generations. Mark in particular is unlikely to be later than 70 CE due to internal evidence, being the only Gospel that seems actively concerned to combat the Sadducees. This sect existed more or less exclusively among the priestly class of Second Temple Judaism, and, as the priests had, for lack of a better word, no job after the year 70, their raison d’être accordingly ceased to exist. Thenceforward they rapidly declined and vanished (there is some speculation that they evolved into or contributed to the Karaite Jews, but this is not widely accepted). Hence, a date later than 70 does not make sense for Mark; New Testament scholars en masse, or indeed off Mass, don’t like dating things any earlier than they are forced to, so 60s it is (and in truth, I don’t know of any particular reason to date it earlier).

†Eusebius was a fourth-century bishop of Cæsarea-by-the-Sea (then the premier see in the Holy Land) and favorite of the Emperor Constantine; his Ecclesiastical History and Life of Constantine are among the most important, if less-than-perfect, documents about the primitive Church and the first publicly Christian emperor. He has been labeled an Arian, though I’m unable to say how justly.

‡I.e., the form used by Jews living in the province of Judæa at the time; as it can be difficult or pointlessly pedantic to trace exactly what form is Hebrew proper versus what is Aramaic, I opted for “Judæan” as a more umbrella sort of term that could apply to either tongue (especially in names, which are more easily borrowed from one language to another).

§Speaking of Solomon, Sh’lomit is also an alternative transcription of the name, or rather title, of a different Biblical figure: the Shulamite, a.k.a. the bride from the Song of Songs. Often taken to be from the village of Shunem, or an otherwise unknown town called Shulem, it is also possible that she was given the name “Sh’lomit” as the bride of Sh’lomoh; it might have been a title derived from the king’s name, either as a unique act or by custom. This is a custom we do know of in Roman culture: part of the pre-Christian Roman marriage service, regardless of the actual names of the parties involved, was for the bride to tell her groom Ubi tu Gaius, ego Gaia, “Where thou art Gaius, I am Gaia”; the groom responded in kind, Ubi tu Gaia, ego Gaius. (This is no proof the Jews ever had the same custom, mind. What it shows is that this sort of thing was known in the ancient Mediterranean, and something similar may have turned up in more than one place.)