This is the second part of the Lord’s Prayer series.

I had originally intended to do the whole second half in this post, but found that both the fifth and sixth clauses of this prayer1 were gigantic, the sixth especially. This might even wind up being a four-parter! At any rate it’s going to be three; let’s now turn to clause number five.

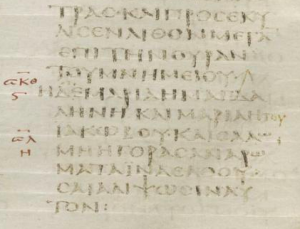

τὸν ἄρτον ἡμῶν τὸν ἐπιούσιον δὸς ἡμῖν σήμερον·

[ton arton hēmōn ton epiousion dos hēmin sēmeron:]

..the bread …our ..the .on-being give .to-us …today;

Give us this day our daily bread;

This is the “asking for things we want” bit of the Our Father. I think it’s important that we not denigrate this, whether out of supposed humility or real embarrassment over our greed, or our ingratitude, or the mere disproportion of our prayers. If we neglect any of the other six petitions, the solution to that isn’t trying to make ourselves feel bad about telling God we want things; all that’s likely to do is make us even more reticent to pray (“for whosoever hath, to him shall be given: but whosoever hath not, from him shall be taken away even that he hath”). And when you come to think of it, while petitionary prayer can be self-centered or selfish, it is at least petitionary: that is, it explicitly acknowledges our dependence on God.

The “Our Father” (1896), by James Tissot.

The real solution to an undue focus on this clause is simpler: attend to the other six clauses too. Put another way, the way to pray more is to pray more, not guilt ourselves into praying less. Luke’s account of the subject positively invites this kind of prayer and, if anything, faults us for not asking for more!

Looking at the wording in Greek more closely doesn’t net us much, with one exception, which we’ll get to in just a sec. The phrasing, though, might perhaps put us in mind of the manna with which God fed the Israelites in the desert. This is the more instructive when we recall not only that the manna was carefully tailored to the people’s actual needs (“he that gathered much had nothing over, and he that gathered little had no lack”), but that it was given in a double portion on Friday, the eve of the Sabbath, in order for Sabbath rest to be an occasion of joy and not of fasting.

But let us turn to that exception. It lies with the word ἐπιούσιον (*ἐπιούσιος is the presumed “dictionary form”), a small but notorious problem-word. It probably does not mean “daily.” That word is ἡμέρᾳ [hēmera], and it’s not in this verse; it would make for an ugly clash with σήμερον if it did, derived as they are from the same word. Unfortunately, ἐπιούσιος only occurs in two places in ancient Greek literature—the other one being the passage in Luke that relates the Lord’s Prayer!

Let’s try a hyper-literal analysis to see what it nets us. The preposition ἐπί [epi] means “on, atop”; it is prefixed to what appears to be a participle, which here is masculine (to match the word for bread, which is likewise masculine). This word can appear independently in the feminine as a noun, οὐσία [ousia], which may look familiar if you’ve read some church history.2 It comes from the verb εἰμί [eimi], “to be,” and therefore means “being”: this would seem to make our problem word mean “on-being.” Our on-being bread isn’t exactly transparent, but you can start to see a few things that might be meant. The bread on which we subsist, maybe? It’s easy to see how that, without quite meaning “daily,” could get treated as if it did.

However, unlike English, Greek doesn’t really use the words “to be” and “to live” as synonyms. (Confronted with our use of “to be” as a casual synonym for “to live,” an ancient Greek might very reasonably point out that a corpse does not live, but it has not ceased to exist.) So “the bread on which we subsist” isn’t likely to mean merely “the bread we live on”; it’s something more like “the bread of our existence”—a prayer that God would supply us with being.

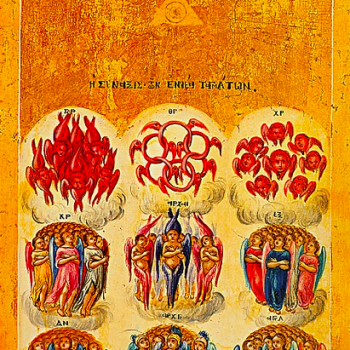

The first day of creation as illustrated by

15th-c. French miniaturist Jean Colombe.

But there is also an ambiguity in the literal translation “on-being.” Being is tenseless; is it talking about the present or the future? According to the late Kenneth Bailey, a scholar of the New Testament and patristics, both.

Now we have … four solutions. These can be summarized as follows: …

-

- the bread of today (time)

- the bread of tomorrow (time)

- just enough bread to keep us alive, and no more (amount)

- the bread we need (amount)

Each of these options is found in the early centuries of the Christian church. … Is there some concept or interpretation that could have given birth to all four of these possibilities? … If so, what is it and where is it found? I am convinced that there is such a starting point and that it appears in the Old Syriac translation3 … the Old Syriac translation of the Lord’s prayer [sic] reads: Lahmo ameno diyomo hab lan (lit. “Amen bread today give to us”). Lahmo means “bread.” Ameno has the same root as the word amen, and … means “lasting, never-ceasing, never-ending, or perpetual.” …

Fear of not having enough to eat can destroy a sense of well-being in the present and erode hope for the future. I am convinced that … at the heart of the Lord’s Prayer Jesus teaches his disciples a prayer that means, “Deliver us, O Lord, from the fear of not having enough to eat. Give us bread for today and with it give us confidence that tomorrow we will have enough.”

—Jesus Through Middle Eastern Eyes, pp. 120-122

It was probably inevitable that this clause would also receive a Eucharistic interpretation at some point, no matter what kind of “bread” it mentioned. This would seem to align this petition of the Our Father not only with the “Bread of Life” discourse from John 6, but the earlier text about “living water” in the same Gospel:

There cometh a woman of Samaria to draw water: Jesus saith unto her, “Give me to drink.” (For his disciples were gone away unto the city to buy meat.)

Then saith the woman of Samaria unto him, “How is it that thou, being a Jew, askest drink of me, which am a woman of Samaria?” for the Jews have no dealings with the Samaritans.

Jesus answered and said unto her, “If thou knewest the gift of God, and who it is that saith to thee, Give me to drink; thou wouldest have asked of him, and he would have given thee living water.”

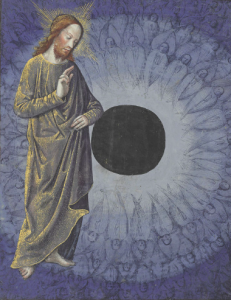

Ikon of Christ meeting St. Photine

(the traditional name of

the “woman at the well”).

The woman saith unto him, “Sir, thou hast nothing to draw with, and the well is deep: from whence then hast thou that living water? Art thou greater than our father Jacob, which gave us the well, and drank thereof himself, and his children, and his cattle?”

Jesus answered and said unto her, “Whosoever drinketh of this water shall thirst again: but whosoever drinketh of the water that I shall give him shall never thirst; but the water that I shall give him shall be in him a well of water springing up into everlasting life.”

—John 4:7-14

There is a good deal more that can be said about this topic, but I’m going to cut it off here for the sake of time. Moreover, the next petition is (I believe) the most-neglected of the seven; it is also, certainly and strikingly, the one Jesus returns to in verses 14-15: For if you remit people their trespasses, your heavenly Father too will remit yours; but if you do not remit people, neither will your Father remit your trespasses.

Footnotes

1To jog your memory: the Our Father has eight clauses, of which the first is an address and the remaining seven are petitions:

Clause i, address: Our Father, who art in heaven:

Clause ii, petition 1: hallowèd be thy name,

Clause iii, petition 2: thy kingdom come,

Clause iv, petition 3: thy will be done on earth as it is in heaven.

Clause v, petition 4: Give us this day our daily bread;

Clause vi, petition 5: and forgive us our trespasses as we forgive them that trespass against us;

Clause vii, petition 6: and lead us not into temptation,

Clause viii, petition 7: but deliver us from evil.

2Specifically, the word οὐσία often pops up in discussions of the history of the Arian heresy. A key term in the Arian debates was ὁμοούσιος [homoousios], “same-being” or “consubstantial.”

3The “Old Syriac” denotes translations of the Bible into the Syriac language—a form of Aramaic, nearly the same as that form which would have been Jesus’ native language—that predate the Peshitta. The Peshitta is the authoritative translation of Scripture used by most churches that employ Syriac as their liturgical language. (These now exist principally in India and Iraq, and are variously aligned: Historically they belonged to the Church of the East, but there are now Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox, and Protestant bodies of the Syriac tradition as well.)

The consensus view is that both the Peshitta, which was probably completed in the early fifth century, and the Old Syriac New Testament were translated from the Greek; the contention of some Syriac churches is that the entirety of the New Testament was originally written in Aramaic, and was translated from that language into Greek. Most scholars dismiss this idea. However, I’ve long wondered whether there might be something in it as regards the Gospel of Matthew specifically. There is a very ancient tradition, going all the way back to Papias in the early second century, that Matthew was first written in “Hebrew,” which might be a casual way of referring to Syriac Aramaic. Furthermore, the literary and cultural center of the Jews in the first century was actually Babylon, as much as or more than Palestine. We know from the example of Josephus, the author of The Jewish War, that it was not unknown for Jewish authors at the time to compose two versions of their own work, one in Greek for Mediterranean consumption and one in Syriac for Mesopotamian readers. While this is very much a speculative possibility, I don’t think it’s off the cards that the author of Matthew could have done with his Gospel what Josephus did with The Jewish War—which, it seems to me, would explain both the tradition that Matthew was originally in Hebrew and the fact that our oldest manuscripts of it are nevertheless in Greek.