The Our Father

This post picks up from the one on Ash Wednesday’s Gospel. As read, the part about what to pray (as distinct from where to pray) is normally skipped; however, it is part of the text as written, and I’ve been wanting to write a bit about the Lord’s Prayer in any case.

This prayer is outlined in two passages from the Gospels. One is in Matthew; the other is in Luke 11:1-13, where the form of the prayer is slightly different (and noticeably shorter), and the accent of the accompanying teaching has to do with perseverance in faith, rather than simplicity of heart as opposed to hypocrisy. The traditional form used by Christians of basically all denominations corresponds rather to the Matthean than the Lucan form of the prayer, insofar as they differ.

Adoración del Nombre de Dios [“Adoration of

the Name of God”] (1772) by Francisco Goya.

Many Christians also make use of a unique doxology as its conclusion: For thine is the kingdom and the power and the glory, forever and ever is its most familiar phrasing in English, inherited from the King James Bible. (Catholics normally add this only during Mass, at the recitation of the Our Father that concludes the Eucharistic canon.) This doxology is traceable to a first- or possibly second-century work, the Didache1; it also occurs in some Greek manuscripts of Matthew, but it is universally agreed to be an interpolation there.

To review the text:

Matthew 6:9b-15, RSV-CE

Our Father who art in heaven,

Hallowed be thy name.

Thy kingdom come,

Thy will be done,

On earth as it is in heaven.

Give us this day our daily bread;

And forgive us our debts,

As we also have forgiven our debtors;

And lead us not into temptation,

But deliver us from evil.

For if you forgive men their trespasses, your heavenly Father also will forgive you; but if you do not forgive men their trespasses, neither will your Father forgive your trespasses.

Matthew 6:9b-15, my translation

Our Father who is in heaven:

…Your Name be sanctified,

…your kingship come,

…your will be done, as in heaven, so on earth;

…give us our bread on which we subsist today;

…and remit us our debts, as we too remit our debtors;

…and do not bring us into trial,

…but rescue us from the oppressor.

For if you remit people their trespasses, your heavenly Father too will remit yours; but if you do not remit people, neither will your Father remit your trespasses.

Detail from The Last Judgment (ca. 1435)

by Fra Angelico, showing sinners

being tormented in hell.

Textual Notes

Instead of going by individual words and phrases that prompt comment, as I usually do, I’m going to take each of the clauses of the prayer and discuss them one by one; the prayer consists in one clause of direct address, followed by seven petitions. (I’m also including transliterations, interlinear renderings, and the traditional English wording of the prayer in red.)

Πάτερ ἡμῶν ὁ ἐν τοῖς οὐρανοῖς·

[Pater hēmōn ho en tois ouranois:]

Father ..our …the in the ..heavens:

Our Father, who art in heaven:

This opening clause immediately establishes two things about Christian prayer. First, it is an inherently communal activity—we pray to our Father in heaven, not to my Father. And second, while we tend to frame fatherhood primarily in terms of affection, it was something much more grave in the ancient world. This is not to say that love between fathers and children was absent, of course! But, to take a metaphor from music, reverence would probably have been the top note in the word’s chord of meanings.

As for “the heavens” rather than “heaven” in the singular (which does occur in the third petition), this is probably no more than a minor variation in phrasing—we have exactly the same variation in English, with both the native English heavens and the Norse-derived skies. It could, also or instead, be an allusion to the tiered heavenly palaces of Merkavah mysticism and Hekhalot literature, but (as far as I know) there is no direct evidence for this theory.

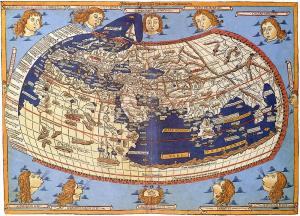

A depiction of the New Jerusalem from

an Armenian Bible of 1645 (source).

ἁγιασθήτω τὸ ὄνομά σου,

[hagiasthētō to onoma sou,]

.be-hallowed the name your,

Hallowèd be thy Name.

This is the first of the seven petitions. This reference to the divine Name deserves attention. (Note how it echoes the Second Commandment, Thou shalt not take the Name of the Lord thy God in vain.)

The Hebrew Bible is much concerned with “the honor of God’s Name,” i.e. his reputation. You may have heard before now about how Semiticsocieties are much concerned with image, honor, and saving face. On one level, this is a little silly; there are probably no cultures where a person’s good name is not considered precious. But Semitic cultures do have, well, a reputation for treating names, human as well as divine, as an aspect of a person’s being. This is where the expression “in the name of” comes from: To speak or act in the name of some person or institution is to do so on their behalf, or even as an extension of them. An extreme example of this attitude can be found in Egyptian hieroglyphic writing, in which a person’s name—usually that of a current or former Pharaoh—might be enclosed in a cartouche to protect it from magical interference. Jewish culture does not appear to have gone in for this (its priesthood were a good deal more ambivalent about magic than the scribes of Egypt); however, Judaic scrupulousness about avoiding desecration of the Tetragrammaton by almost never pronouncing it is famous.

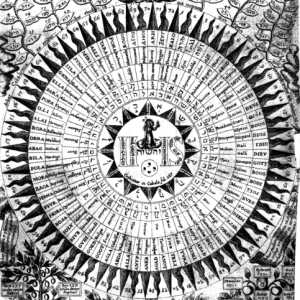

A diagram of the names of God from Oedipus

Ægyptiaca (1652-1654) by Athanasius Kircher, S. J.

To “hallow God’s Name,” then, is to hallow him, his identity, his self. And what does hallowing something mean? To be perfectly truthful, I don’t know. I have a few educated guesses that I hope you’ll find illuminating, but they are guesses, and should be accepted (if at all) only as such.

First, hallow is the verbal form2 of the same root from which we get the adjective holy; “to consecrate” is now the more common word in English. Hallow and holy (from the Anglo-Saxon ᚻᚪᛚᚷᛁᚪᚾ [halgian] and ᚻᚫᛚᛁᚷ [hælig]) are related to a string of words that, originally, had to do with bodily integrity or well-being—hail,3 hale, heal, and whole are good examples. In English, then, we are implicitly saying something like “May your good name be kept undamaged” or “May no ill be spoken of you.”

It would, of course, be nonsense to pray this with a mindset of protecting God, as though he were at risk of dealing with uninsured medical bills or something. It is, rather, a prayer that sets our priorities—one that asks that God be to humanity what he is in himself; and thus, ultimately, a prayer for us to behave in a certain way. (The fact that God’s Name is nevertheless the subject here, and of a passive verb, may serve to hint at the fact that it is never entirely within our control how we ourselves behave, let alone what happens to other things and people, which turns this into a prayer for grace.) The same goes for the original tongues, as all prayer that God be the object of an action must be essentially of this kind.

A rood from the abbey church of Wechselburg,

Germany. Photo by Wikimedia contributor

Kolossos, used under a CC BY-SA 3.0 license

(source).

But the analogies present in other languages are also instructive. In Greek, we again have a string of interrelated words, with ἅγιος [hagios] “holy,” ἁγνίζω [hagnizō] “sanctify,” ἁγνεία [hagneia] “purification,” etc.; however, in meaning, this Greek string seems to be closer to its primitive proto-Indo-European roots, which are associated simply with priestly, sacrificial affairs, without shedding any special light on them. Intriguingly, the Latin sacer (one of its two most common adjectives meaning “holy,” the other being sanctus—both together forming our emphatic adjective “sacrosanct”) seems to derive from an Indo-European verb meaning “to make a treaty,” almost echoing the Judaic association of holiness with the Lord’s covenant.

But of course, this prayer was probably first delivered in Aramaic.4 Now, I don’t speak Aramaic, and my command of Hebrew is … well, isn’t. I know something about both languages, but that’s rather a knowledge of linguistics than of languages—structural more than practical knowledge. I’ve therefore done my level best not to go beyond publicly available facts here, and am very likely missing stuff.

Semitic languages don’t build words from stems like English or Latin do. (For example, stem is a stem, to which you can add the noun pluralizing suffix -s for multiple stems, or the verb past suffix –ed if something has stemmed from it.) Semitic languages build words from radicals—groups of consonants (three is typical) that encode a general meaning; vowels, and additional consonants and affixes can then be inserted in various ways. A famous example is based on Arabic: perhaps K-T-B is a radical associated with things like writing and reading. The word for “book” might be katab, with a plural created by inserting new vowels (e.g. kitub), or maybe a prefix like ma– would turn it into a word for “a place of books,” i.e. a school, or maktab.

There is a pan-Semitic radical, spelled ק-ד-ש [q-d-sh] in Hebrew letters, that frequently forms the source of words for holiness and religious things in Hebrew: holiness as a quality is קֹדֶשׁ [qòdhesh]; one of the mourners’ prayers is the קַדִּישׁ [qadîsh]; the Temple itself was the מִקְדָּשׁ [miqdâsh], “the holy place.” Now, the fact that a given radical was used in Hebrew doesn’t prove it was used the same way in Aramaic (or indeed that it was used in Aramaic at all); however, at least one Syriac version of the Lord’s prayer does record the verb of this clause as—and I’m not even going to try to get the Syriac script right!—netqadaš, which again seems to be from the same radical.

The meanings of the radical ק-ד-ש, or at any rate the ones I was able to find, do trend religious quite consistently; but it’s hard to draw much from that alone. I was hoping I might find out more about the remote origins of the radical—for instance, “set apart” is often used as a synonym or alternate rendering for “holy”: it would be interesting to know whether this is because English speakers already associated holiness with separate-ness, independently as it were, or if this was an association we picked up from exposure to the Hebrew Bible. Alas, at least for now, what it means to “hallow God’s name” beyond treating him reverently (if indeed there is anything to it beyond that) remains obscure to me.

ἐλθέτω ἡ βασιλεία σου,

[elthetō hē basileia sou,]

..come the kingship your,

Thy kingdom come.

One striking grammatical wrinkle in the Our Father is that the main verbs of its first three petitions are third-person imperatives. These operate exactly like the second-person imperatives we’re used to, except that the imperative is addressed to some third party (often an abstraction or something similarly absent)—the set phrase “be it so” is an English third-person imperative, probably our only one. These were more or less obsolete in the normal Koine Greek of the time—their appearance in the Gospels was presumably to represent something in Aramaic that couldn’t be conveniently rendered otherwise.5

γενηθήτω τὸ θέλημά σου, ὡς ἐν οὐρανῷ καὶ ἐπὶ γῆς·

[genēthētō to thelēma sou, hōs en ouranō kai epi gē:]

come-to-be the .will ..your, .as .in heaven also on earth;

Thy will be done, on earth as it is in heaven.

An 18th-c. Persian astrolabe, photographed

by Andrew Dunn, used under a CC BY-SA 2.0 license (source).

This clause contains one of two uses in this prayer of the word ὡς, “as.” This innocent-seeming word can pack more, and more terrifying, meaning than it usually gets credit for. The request that God’s will in heaven be equally done on earth probably doesn’t sound terrifying to most of us. Wait for it.

It is also interesting to note that, apparently, desiring God’s “kingship” and praying for his “will” are two distinct things. In terms of our habitual associations, the “kingdom of God” is more eschatological, more associated with “the world to come,” whereas the will of God is something to be embraced in the present; it’s possible that that’s what’s going on here (though I have a hunch there are further levels of meaning I’m not seeing). It is striking how human beings need some kind of assurance of both current and future meaning or importance to find our actions meaningful. Presumably that is why we need to actively commit both to the care of God.

Second half to come.

Footnotes

1The name of this work literally means “teaching, doctrine.” It is one of the most ancient Christian documents outside the New Testament itself, and may have been written while some of the Apostles were still alive. Its formulation of the Lord’s Prayer, which includes the doxology, appears in Didache 8:3-10.

2That is, in this context, “hallowed” is the present passive participle of the verb. Hallow can also be a noun, referring to holy places, objects, or people (though this nominal formulation of the root is now virtually extinct except in a handful of set phrases like “All Hallows’ Eve”).

3The greeting, not the precipitation. Like the ancient Latin salvē/salvēte, the greeting hail literally meant “Be well” in Middle English; the term survives only in the word “to hail” as in “to solicit, flag down; to greet.” The word hello, however, appears to come from an unrelated root.

4Not certainly; even in the Holy Land, there were Jews who spoke Greek as their mother-tongue in the first century. But Aramaic was by far the more common, and was in the Persian sphere of influence much what Greek was in the sphere of the Roman Empire.

5Funnily enough, this is why many Bible translations not otherwise linguistically conservative long maintained the thou-ye distinction: it was a way of distinguishing singular from plural in the second person, something modern English really doesn’t have an easy means of doing.