NOTE: As of 28 December 2023, this post has been lightly edited throughout; contrary to my usual practice, I have not highlighted the edits individually, as I felt the notes would get pretty tedious if I did.

I’ve decided to change things up a little, and do the epistle for Christmas Day. It’s from one of my favorite books of the New Testament, namely the letter to the Hebrews. There are some really fascinating aspects of this book that I’ve never heard talked about in Catholic circles, and only occasionally in Reformed ones; so, I’d like to share a couple of things up front.

The Author of Hebrews? Who Is She?

A photograph of part of the manuscript collection called

the Chester Beatty papyri (specifically, the manuscript now known

as P. Chester Beatty I). Discovered in the 1930s, these papyri date

mainly to the third century, and a few go back to the second.

Hebrews was once widely believed to be by St. Paul. This used to be kind of wild to me. The letter nowhere includes his literal-and-metaphoric signature, the “large letters I write with my own hand,” and Paul implies in II Thessalonians in 2.2 and 3.17 that any purported epistle without his authenticating “large letters” is a forgery—nor does it actually claim, at any point, to be his work.* (Almost as tell-tale, in my opinion, is the fact that the author of Hebrews sends no greetings to anybody in particular, something neither prayers nor tears nor curses could have stopped St. Paul from doing: when writing to the Roman church, which he had not even visited in person yet, he spends the bulk of the last chapter on multiple iterations of Say hello for me to Fred, everyone who lives in Fred’s house, their families, their families’ friends, their families’ friends’ pets, etc.) Twentieth-century scholar Donald Guthrie remarked that “most modern writers find more difficulty in imagining how this epistle was ever attributed to Paul than in disposing of the theory.”

However, to be fair, that does point us toward one of the principles of manuscript criticism, a rule known as lectio difficilior or (in full) lectio difficilior potior: “the more difficult reading is the more preferable.” This may seem counterintuitive; most of the few errata** we find in books today are caused by faulty machinery, and are in some cases obviously nonsensical! But remember, we’re talking about a period when all texts were copied by hand, and the reproduction of books therefore inherently involved people, who have intelligence and creativity. This is pretty much the opposite of a printing press. It makes copies without any capacity to understand what it is copying, and it cannot initiate edits of any kind: even errata have to be caused by either human error in the initial input, or mechanical issues (keys breaking, ink running out, a piece of debris falling into the machine, etc). A scribe, on the other hand—if he comes across an unfamiliar word or grammatical form, or an idea that sits poorly with his understanding of things, especially religious things—will have the wherewithal to introduce simplifications or “corrections” to the text. And conversely, he is far less likely to introduce a lectio difficilior where one did not previously exist.

Of course, what we’re discussing here is a question about the origin of a text, not the text itself, so not all the rules of manuscript criticism are going to apply or not in the same manner. But the point is that the very existence of such a strange tradition about the authorship should prompt us, not to accept it without reservation! but to dig a little deeper and see if there is anything more to it. And there is a little more to this one; apparently, St. Clement of Alexandria (head of the catechetical school in that city in the early third century) asserted that St. Paul had written it, originally in Hebrew, and that someone else, e.g. Luke, translated it into Greek later. It has even been proposed that Paul left his name off of this letter precisely because he was writing to a group of Hebrews, who might be predisposed to distrust or dislike Paul and his radical approach to the Torah. I will admit frankly, I find the argument in support of Pauline authorship convoluted and unpersuasive; but I hope I have done justice to it.

Erasure, She Wrote

A number of theories have been put forward about just who did write Hebrews. Acquaintances of Paul, who might be supposed to have been influenced by his theology (thus explaining the similarities and the confusion with the apostle himself), are typically favorites. Tertullian believed St. Barnabas wrote it; a few other church fathers suggested St. Clement (later the fourth Pope) or St. Luke the Evangelist, and Martin Luther suggested St. Apollos. Authorship by St. Priscilla has been a persistently popular minority theory since 1900, when it was first proposed by Adolf von Harnack (on the grounds that it ought to be a close associate of Paul and Timothy, but one whose name the primitive church would find embarrassing as the author of a portion of Scripture).† There are also a few surprisingly good reasons to consider St. Silas,‡ Paul’s companion on his second missionary journey.

A handful of other figures could surely be proposed: Thomas the Apostle, because of his concern with faith as “the evidence of things unseen”; Titus, because he was another protégé of Paul; Thecla, for the same reason; Joseph of Arimathea, because he was educated enough to be a member of the Sanhedrin; Agabus, because he is mentioned in Acts 11 as having the gift of prophecy; the real Dionysius the Areopagite, because it’s about time he got credit for something; Mary Magdalene, because it sort of provides a positive counterpart to the Gnostics’ annoying habit of using her as a figurehead against orthodox leadership; Eutychus of Troas, because why not; etc.

This question typifies many (though far from all) of the controversies in New Testament studies in three respects:

- It is, for academically-inclined types, very interesting;

- It has many plausible answers, several convincing ones, and a handful of very stupid ones; and

- It is of no consequence whatever.

The Secret History

However, the fact that St. Paul didn’t write Hebrews doesn’t mean it shares nothing with his work. They both seem to have a penchant for long sentences, for one thing—long enough that it does technically impact the way both writers get translated. It’s not uncommon for participles or even adjectives in the Greek to be represented as verbs in the English, in order to allow for shorter sentences.

An engraving illustrating Ezekiel’s vision in Ezekiel ch. 1.

Created by Matthäus Merian, 1670.

More importantly, both authors shows signs of the influence of Merkabah and Hekhalot literature, forms of Judaic mysticism§ (merkavah [מֶרְכָּבָה] is a Hebrew word for “chariot,” while heykhaloth [היכלות—couldn’t find the vowel pointings for this one] means “palaces”). These flourished mainly among Palestinian and Babylonian Jews, beginning in the second or first century before Christ. Merkabah mysticism originates with the vision of the prophet Ezekiel, recorded in the first chapter of his book, in which various kinds of angelic beings are associated with the divine throne, carrying it or even constituting it. In some works of the Merkabah tradition, some of these angelic beings are appointed as revelators of divine wisdom to humanity, or as guides conducting visionaries through the heavenly realms of God’s dwelling—which brings us to the Hekhalot literature. This is closely related not only to the earlier Merkabah stuff, but to apocalyptic material. It concentrates on visions achieved by, or granted to, certain devout individuals, usually illustrious rabbis (who do not always return from these experiences with their souls or their sanity intact); the Book of Enoch is an example.

There are traces of these mystical traditions in the New Testament. The book of Revelation carries signs of Merkabah and Hekhalot ideas, sharing with Hebrews the image of a “heavenly tabernacle” or temple. St. Paul, too, sounds like a Hekhalotic mystic in II Corinthians when he mentions being “caught up to the third heaven and hearing things it is not lawful to utter”; the command to “seal up what the seven thunders have said” in Revelation is an obvious parallel. It may again be at work when he states, in passing in Galatians, that Moses received the Torah “through angels by the hand of a mediator.” I’d like to share more about this, but the truth is, I don’t know much more than I’ve put down here! (I hope to get a chance to read up on it in more detail, once the financial hit of December stops making my pockets hurt.)

Alright! Let’s jump into the text.

RSV-CE

In many and various ways God spoke of old to our fathers by the prophets; but in these last days he has spoken to us by a Son, whom he appointed the heir of all things, through whom also he created the world.1 He reflects the glory2 of God and bears the very stamp of his nature,3 upholding the universe by his word4 of power. When he had made purification5 for sins, he sat down at the right hand of the Majesty on high, having become as much superior to angels as the name he has obtained is more excellent than theirs. For to what angel did God ever say,

“Thou art my Son,

today I have begotten thee”?

Or again,

“I will be to him a father,

and he shall be to me a son”?

And again, when he brings the first-born6 into the world,7 he says,

“Let all God’s angels worship8 him.”

My Translation

At many points and in many ways, God spoke of old to the fathers in the prophets; on the last of these days he spoke to us in his Son, whom he set up as the heir of all things, through whom he made the worlds1; who, being the radiance of his glory2 and the seal of his essence,3 and bearing up all things on the sentence4 of his power, having made a cleansing5 of sins, sat on the right of the Great One in the heights, having become as much stronger than the messengers as the name he has inherited differs from theirs. For to which of the messengers did he say “You are my Son, I have begotten you today”? And again, “I shall be to him for a Father, and he will be my Son”? Again, whenever he brings the firstborn6 into the known world,7 he says: “And let all God’s messengers lie prostrate8 before him.”

Textual Notes

As it has come up in more than one passage already, I haven’t explained why I use the literal translation messenger instead of the conventional “angel.”

1. World/worlds: the Greek here, aiōnas [αἰῶνας], is a plural form of aiōn [αἰών], whose meanings and derivatives I complained about in textual note 6 of this post. Depending on context, you can translate it as “life,” “age,” “time,” “world,” “generation,” and the list goes on. As those translations hint, the underlying idea is something along the lines of “the typical period of a human lifetime,” and the meanings that branch away from this usually do so by becoming more specific and/or metaphorical.

In terms of its origins, the English world is low-key perfect for this, since it comes from wer–ald, “man age.” Unluckily, its English meaning has drifted more toward the geographical than the temporal for us. This is a natural development, for multiple reasons; but it does give the impression, when an ancient author writes that God “made the worlds,” that he is talking about God’s creation of the planets—which is true, but not the point the author of Hebrews is making. The aiōnas are, apparently, something more like dispensations, along the lines of the gospel references to “this age and the age to come.” Why the translators of the RSV decided to turn the plural into a singular, I’m not sure. Perhaps they took aiōnas to be a shorthand for something like “human generations in general,” and felt that “the world” duly summed that concept up.

2. He reflects the glory/being the radiance of his glory: these each translate the noun phrase apaugasma tēs doxēs [ἀπαύγασμα τῆς δόξης]. This idea of a reflection or luminescence seen as if in a mirror is used a good deal in ancient and medieval literature; they seem to have found mirrors fascinating—the Book of Enoch attributes the craft of making mirrors to the corrupt angels who figure in the more “mythological” interpretation of Genesis 6.|| I’m not in a good position right now to say more about this, but hopefully I’ll be able to come back to it some time soon.

Hieronymus Bosch, The Fall of the Rebel Angels, ca. 1510

3. The very stamp of his nature/the seal of his essence: the Greek here is charaktēr tēs hüpostaseōs [χαρακτὴρ τῆς ὑποστάσεως]. Charaktēr is the origin of the English term character, which originally had the primary sense (now less common, but still current) of a character in an alphabet. With the ancient charaktēr, often in the form of a signet ring or similar object, the idea was to produce an exact replica of the pattern by pressing it into something soft (such as clay or wax). This allowed the authentication of documents, and thus of their contents: the more unique the seal, the harder it was to fake, and the surer the authentication it provided.

The word hüpostasis [ὑποστάσις], or to give its more conventional transliteration, hypostasis, may look familiar to those who have studied the history of theology. It is the term for “person” that was ultimately settled on in Greek at the ecumenical councils, especially Chalcedon: the differences “in” the Trinity are the three hypostases, while the unity in Christ is his one hypostasis; but of course, when we say “settled,” we are intentionally leaving aside those it didn’t settle.

The origin of the Greek word and its relationship to Latin (as the two languages, like ours, descend from proto-Indo-European) suggest that it was not an inevitable choice for the technical jargon of Christian doctrine. As far as etymology is concerned, hüpostasis corresponds in Latin to substantia: hüpo and sub are related prepositions mainly meaning “under,” and the relationship of stasis and –stantia to the English stand hardly even calls for explanation. Both the Greek and the Latin thus both, taken hyper-literally, mean “that which stands beneath,” and thus something like “underlying identity” or “persistent reality.” It is easy to see how this could become the word for the concept we usually use person for in English. By contrast, substantia does not mean “person” at all in Latin, but “essence, nature, being” (as in the contrast between a substance and its accidents). This in turn suggests that the schisms which created the Church of the East and Oriental Orthodoxy, far from being real differences in ideas, may have been quarrels largely, perhaps even wholly, over wording. And while that is a depressing reflection on Christian history, it is also an encouraging thought for the possibility of reunion.

The Church of St. George, one of the many celebrated rock-hewn churches

of Ethiopia (source); the Tewahedo Churches of that country and of Eritrea

(which became fully independent of the Ethiopian hierarchy in 1993)

are historically important members of the Oriental Orthodox communion.

I go through these details because they are interesting and, historically speaking, important. However, as it happens, it hardly matters whether God’s person or nature is meant in this particular verse! Both fit the immediate context.

4. Word/sentence: the word here is not logos, like the “Word” of John 1, but rhēma [ῥῆμα] (which comes from the same root as the word rhetoric). Like the English word sentence, rhēma could mean “thing said, utterance” in a general way, but also the verdict of a judge in a legal case.

5. Purification/cleansing: either translation is perfectly defensible. Nowadays, words like pure and purify seem to me to be restricted to religious or chemical contexts—you can clean a kitchen or cleanse a utensil, but you probably aren’t going to purify your kitchen or utensil. Obviously, a religious word is far from inappropriate here! But since the word in question was also the perfectly ordinary word for cleaning anything, I went with what seemed to me the more commonplace term.

6. First-born/firstborn: this turned out to call for quite an extensive commentary! See the final section, below, for that commentary.

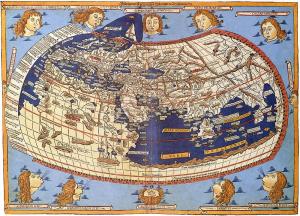

7. World/known world: deciding on the English here was a bit of a toughie. The phrase oikoumenē gē [οἰκουμένη γῆ] means “the inhabited world” (or more literally “the househeld earth,” which for some reason I love as a phrase). This was a stock phrase, normally shortened to oikoumenē; in the imperial period, it became roughly synonymous with the Mediterranean/the Roman Empire/the general territory that the Romans felt should be the Roman Empire if the barbarians would kindly stop ruining everything. (The word passed through Latin into erudite English as Oecumene—often spelled without the o, which had ceased to be pronounced in Latin—and is also related to the term ecumenism.)

This is not to say the Greeks or Romans didn’t know there was more land north of them in Europe, or south of them in Africa, or east of them in Asia. They did, and indeed, they knew they had complex societies in them, like the Scythians, Ethiopians, Persians, and Indians; the Silk Road had even connected China with the Mediterranean, more than a hundred years before Christ. The oikoumenē was “the inhabited world” in roughly the same way, and for roughly the same reasons, that we speak of “the known world” in the period before the Age of Exploration: we are, in principle, aware that the Americas, Oceania, Australasia, and sub-Saharan Africa were perfectly well known to the people who, you know, lived there. But, (a) we’re speaking from “our” perspective, and (b) we’re not so dedicated to abolishing mild instances of cultural snobbery that we’re willing to forego a useful expression.

8. Worship/lie prostrate: this verb, prosküneō [προσκυνέω], is a fairly common one in the New Testament and patristic literature, for reasons that are probably obvious! “Worship” is the conventional English rendering, and it’s fine as far as it goes; its Anglo-Saxon root, weorþsċype (what a visual delight!) is literally worth-ship, which of course lies behind the archaic courtesy “Your worship.”

However, the Greek is a good deal more vivid. It is a derivative of the verb küneō [κυνέω], “to kiss,” a gesture our ancestors associated far more with affection and reverence than with eroticism. The prefixed preposition, pros [πρός], isn’t all that remarkable—it just means “towards” or “at,” by itself. However, Greek is quite like English in assigning fairly specific meanings to prepositionalized verbs: “to overlook” something is not just to look at the space immediately above it, and likewise, prosküneō-ing someone didn’t mean making duckface at them. Even lie prostrate, while it makes convenient English, is less than the truth. The literal action of this verb was to kiss the ground in someone’s presence, typically near their feet. (In this sense, in Catholic ritual, we “worship” only once a year, during the Good Friday liturgy—and even then, only the celebrants fully “worship.”) I refrained from using the stock phrase “worship the ground he walks on” because it felt too wordy, but, in a highly colloquial context, the equivalence would be pretty exact!

“The Firstborn”

We use this term simply as a synonym for “eldest child.” However, in ancient Judaism, the firstborn (bekhor [בְּכוֹר] in Hebrew, prōtotokos [πρωτότοκος] in Greek) was not merely a cardinal number but a specific social, ritual, and legal role. This position was, by explicit law, reserved to a man’s eldest son, regardless of the favor or seniority of his wives (if he had more than one); furthermore, only a son could occupy it—i.e., if a daughter, or even a miscarriage of unknown sex, came first, then ritually speaking the family had no firstborn, no bekhor—and he received a double portion in the inheritance.

This double portion would have been the birthright that Esau “despised,” selling it to Jacob basically for a bowl of chili. Between Esau’s strangely blasé attitude (or possibly a worrisomely exaggerated passion for chili), and the boys’ mother Rebekah having a degree from the Scooby Doo School of Cunning Schemes, the fates of Esau and Jacob form a striking exception to the normal customs of the day. That said, as I believe Joseph Campbell pointed out in The Masks of God: Occidental Mythology, Jacob’s getting the edge against Esau does fit into a wider pattern in the Torah. The aesop of Rebekah’s dream during her pregnancy, “the elder shall serve the younger,” is a frequent motif in the Hebrew Bible. Judah was the smaller and less prosperous kingdom of the post-Solomon divided monarchy; David was the younger, less experienced, and indeed upstart candidate for the throne when compared with Saul (besides being the youngest in his own family); Israel as a people are the very dregs of society in the book of Exodus; Joseph is not only Jacob’s most darling son, but the most fortunate of the twelve; Isaac himself was the younger brother of Ishmael; all humanity, mythically, are the descendants not of Adam’s eldest or even his second son, but of Seth, his third. The Torah repeatedly indicates an unlikely (to our minds) divine preference for the weaker, the less conspicuous, the less honored.

To Christians, this may make it intriguing that, in the parts of the Bible that are set after the Mosaic Covenant, God frequently describes Israel as his “firstborn.” In their immediate contexts, I gather these references are mostly if not all to the sacerdotal function of Israel among the nations, the goyyim, and the same is true of the “Servant Songs” in Isaiah 40-59; the Christian meaning (if one accepts it) operates at the allegorical level of the text, not the literal.

Famously, firstborns had to be “redeemed” by the sacrifice of a lamb—or, for those too poor to afford a lamb, a pair of pigeons or doves, as we see St. Joseph and the Mother of God offer in Luke 2. (Note the quotation from Leviticus used by Luke in that passage: every male that openeth the womb shall be holy to the Lord, which may have meant in the ancient world, and is now held by most rabbis, to mean that an eldest son born via c-section is not a firstborn in the required sense). The Torah is not entirely explicit what it is firstborns are redeemed from, and I understand there are at least three theories. I’ll be needing adjectives for these in a moment; as I couldn’t figure out how to make an adjective from the name “Isaac” (is it Isaachian? Isaacal? Isaacine?), I shall call them the Levitical, the paschal, and the Morian theories.

An illuminated capital from a fourteenth-century

Icelandic manuscript, depicting the angel’s intervention

during the binding of Isaac.

- The Levitical theory. Some believe the redemption of the firstborn corresponds to the Levites being set aside by God as the tribe devoted to the temple’s service. The Levites received this as a peculiar honor after the episode of the Golden Calf—yet in an earlier passage, God had declared the Israelites in general to be “a nation of priests,” suggesting that the remainder of Israel, or at least the other firstborn, have been in some sense or to some extent released (and indeed barred) from this duty.

- The paschal theory. Others think it alludes principally to the sparing of the Israelites’ firstborns from the tenth plague in Egypt, hence the sacrifice of the lamb, as well as the fact that firstborns are expected in at least some Judaic traditions to fast on the eve of Passover.

- The Morian theory (named after Mount Moriah). It may also be a recapitulation of the (non-)sacrifice of Isaac required of Abraham. That may itself have been something of an object lesson: infant sacrifice was common among many Canaanite peoples, and the episode in Genesis 22 may be one of the multiple ways in which the Hebrew conveys that human sacrifice is against the will of God—”one of the multiple ways” because, of course, the lesson was not consistently heeded.

Any or all of these might be correct. They all also fit into various aspects of Christ’s life and ministry, and even specifically into the themes of the book of Hebrews! Christ’s office as priest, the most heavily accented theme of Hebrews, matches the Levitical interpretation; his identity as the victim offered by the priest (in Hebrews, himself) suits both the paschal and Morian theories. As it happens, both of them are also historically suited to the Feast of Childermas, the day on which the edited version of this post—including the whole of this sixth textual note—has gone up.

An illumination of the massacre of the Holy Innocents (see Matthew 2.1-18)

from the Codex Egberti, a late tenth-century manuscript probably produced

in what is now southern Germany.

Footnotes

*A handful of scholars, past and present, have identified Hebrews as pseudepigraphical. Pseudepigrapha are not quite the same thing as “forgeries,” or not in all cases, but it amounts to the same thing in this context. This classification actually gets under my skin a little, because it seems not just insolent, but ridiculously unfair, to accuse the author of lying about being St. Paul when he never said he was St. Paul.

**Errata are printing errors. The category is technically a little broader than misprints, embracing unintentional omissions, warped or broken letters in a press, etc., but if you think of them as misprints, it’s not incorrect enough to matter.

†This is the Priscilla of Priscilla and Aquila, friends of Paul’s and fellow Jewish Christians. They are mentioned three times in the eighteenth chapter of Acts, and in the concluding greetings of three of the Paulines (Romans, I Corinthians, and II Timothy). Priscilla is listed first in four of the six mentions of the couple; furthermore, in Acts, on hearing St. Apollos preaching Christianity in the synagogue of Corinth and apparently spreading unintentional misinformation, the pair took him unto them and expounded the Way of God more perfectly; these facts, taken together, have been interpreted as signs that Priscilla was both an insightful theologian in her own right, and a more imposing personality than her husband (as we might otherwise expect “Aquila and Priscilla” in all cases).

In my opinion, the argument for Harnack’s view could be called “dubious” if we were feeling generous—not because there is anything implausible about a woman contributing to holy Scripture, but because there seems little cause to make a specific case for her as opposed to, say, the Mother of God, or Phoebe, or Junia, or Evodia, or Syntyche, or any other woman in the New Testament—that is, if we’re granting in the first place his claim that Hebrews’ anonymity implies female authorship, because why else would a name be omitted?—when in reality, we have mountains of anonymous works and pseudepigrapha from antiquity. Anonymity suggests just what it says: nothing. In fact, that there should be no trace of St. Priscilla’s authorship, even though she was a familiar figure to many churches, seems quite unconvincing to me. Moreover, while the ancient world was more misogynistic than ours, Christians had special cause to honor women (especially the Mother of God, St. Mary of Bethany, and, if she was a separate person, St. Mary Magdalene), and they certainly had no more cause to be misogynistic than their antique surroundings. Said surroundings did feature a small, but recognizable, class of female authorities and intellectuals: Maria the Jewess, a celebrated first-century alchemist, is one example, and (albeit from a few centuries later) the brilliant Neoplatonist scholar Hypatia is another. To me, none of this makes it likely either that the identity of the author of Hebrews was suppressed due to her gender, or that her identity was Priscilla in particular.

However. It does bear saying that even if there’s little to no evidence for it, there’s nothing especially wrong with this hypothesis either, or nothing I can think of. The idea that St. Priscilla was a wise and eloquent theologian squares perfectly well with the New Testament; and the existence of a bad argument for an idea does not make the idea bad.

‡Silas is likely the same person as Silvanus, who is mentioned briefly by both SS. Paul and Peter and who assisted in the writing of a handful of the Pauline epistles, perhaps as an amanuensis. Some traditions identify Silas with, and others specifically distinguish him from, a Silas who was (according to a traditional list in the East) one of the Seventy Disciples of Luke 10. Additionally, the late Jesuit scholar Joseph Fitzmeyer noted that “Silas” was the Greek adaption of the Aramaic name Seila [שְׁאִילָא], which is, ironically, a form of the name Saul!

§These far antedate the Kabbalah, the only form of Judaic mysticism most people are familiar with today. Incidentally, since it’s come up, it should be cautioned that popular versions of the Kabbalah are largely degraded; there aren’t many casual students of the Talmud outside of Judaism, and—as it is the Talmud that furnishes the principles upon which nearly all religious Jews interpret and apply the Torah—you can’t even lay the foundation on which the Kabbalah is built without knowing the Talmud.

||For any readers who are unfamiliar, here is a brief introduction. The pertinent text from Genesis is as follows: And it came to pass, when men began to multiply on the face of the earth, and daughters were born unto them, that the sons of God saw the daughters of men that they were fair; and they took them wives of all which they chose. … There were giants in the earth in those days; and also after that, when the sons of God came in unto the daughters of men, and they bare children to them, the same became mighty men which were of old, men of renown. The flood narrative follows. That phrase, “the sons of God,” is conspicuous, because it doesn’t occur often in the Hebrew Bible, and it has been interpreted in two chief ways by Christians. St. Augustine championed the idea that “the sons of God” were descendants of Adam’s third son, Seth, and the “daughters of men” were descendants of Cain, whom the Sethites married, resulting in their corruption. The other interpretation famously appears in the Book of Enoch. There, “the sons of God” means the same thing it does in its other appearances in the Hebrew Bible: angels, or some specific kind of angels. Enoch actually presents a whole catalogue of these angels who forsook their stations and married human women; their children, human-angelic hybrids, were the “giants” of the King James, or in Hebrew, the nephilim [נְפִילִים], which means mighty ones or fallen ones. As a bonus, these defiling angels introduced human beings to many sciences and technologies, including many forms of magic, instruments of warfare, cosmetics, and mirrors.