A Detour to the Mount

As I’d made little progress in my translation of last week’s Gospel text and wasn’t finding I had much to say about it, I’ve decided to skip both it and this coming Sunday’s text, in favor of the Gospel for Ash Wednesday (in hopes of getting this post, which I suspect will be a two-parter, finished before that day).

The inaugural Lenten Gospel passage comes from Matthew 6, which is the middle chapter of the Sermon on the Mount. Thus, by happy chance, even though we’re stepping outside of Luke, we’re keeping thematically consistent, since the Sermon on the Plain largely corresponds to the Sermon on the Mount. There is rather a long omission in the middle of the reading, which as usual I have added to the translation; the upshot is, this text is rather a long one—hence my guess that this will be a two-parter; the Lord’s Prayer just begs to be commentated on. So let’s dig right in.

6th-c. ikon of Christ Pantokrator (Almighty),

preserved in the Monastery of St. Catherine

on Mount Sinai—a rare example of a surviving

ikon from before the Iconoclasms.1

Matthew 6.1-6, 7-15, 16-18, RSV-CE

Beware of practicing your piety before men in order to be seen by them; for then you will have no reward from your Father who is in heaven.

Thus, when you give alms, sound no trumpet before you, as the hypocrites do in the synagogues and in the streets, that they may be praised by men. Truly, I say to you, they have their reward. But when you give alms, do not let your left hand know what your right hand is doing, so that your alms may be in secret; and your Father who sees in secret will reward you.

And when you pray, you must not be like the hypocrites; for they love to stand and pray in the synagogues and at the street corners, that they may be seen by men. Truly, I say to you, they have their reward. But when you pray, go into your room and shut the door and pray to your Father who is in secret; and your Father who sees in secret will reward you.

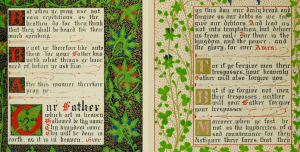

Matthew 6:5-16a from the illuminated book

The Sermon on the Mount (1845) by Owen Jones.

And in praying do not heap up empty phrases as the Gentiles do; for they think that they will be heard for their many words. Do not be like them, for your Father knows what you need before you ask him. Pray then like this:

Our Father who art in heaven,

Hallowed be thy name.

Thy kingdom come,

Thy will be done,

On earth as it is in heaven.

Give us this day our daily bread;

And forgive us our debts,

As we also have forgiven our debtors;

And lead us not into temptation,

But deliver us from evil.

For if you forgive men their trespasses, your heavenly Father also will forgive you; but if you do not forgive men their trespasses, neither will your Father forgive your trespasses.

And when you fast, do not look dismal, like the hypocrites, for they disfigure their faces that their fasting may be seen by men. Truly, I say to you, they have their reward. But when you fast, anoint your head and wash your face, that your fasting may not be seen by men but by your Father who is in secret; and your Father who sees in secret will reward you.

Le Pater Noster or “The ‘Our Father'” (ca.

1890s?) by James Tissot.

Matthew 6.1-6, 7-15, 16-18, my translation

Take care not to perform your justice in front of people, so as to be seen by them; if so, you have no reward from the Father that is in heaven. So, whenever you give charity, do not sound a trumpet before yourself, as the impostors do in the synagogues and in the streets—thus will you be glorified by people; I tell you, ‘amīn, they have received their reward. When you are giving charity, left hand, do not know what your right hand is doing, so that your charity is hidden; and your Father who sees what is hidden will pay you back.

And whenever you pray, do not be like the impostors; for they love to pray in synagogues and standing in the corners of broadways, so that they may appear to people; I tell you, ‘amīn, they have received their reward. But you, whenever you pray, go into your store-room and close the door—pray to your Father in that hidden place; and your Father who sees what is hidden will pay you back.

And when praying, do not blather like those of the nations, for it seems to them that they will be listened to on account of their wordiness; so do not be like them, for your Father knows what you need to have before you ask him. You are, then, to pray thus:

Our Father who is in heaven:

…Your Name be sanctified,

…your kingship come,

…your will be done, as in heaven, so on earth;

…give us our bread on which we subsist today;

…and remit us our debts, as we too remit our debtors;

…and do not bring us into trial,

…but rescue us from the oppressor.

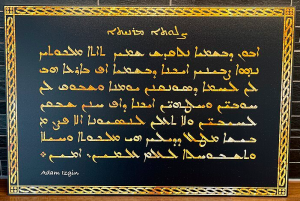

The Lord’s Prayer in the Syriac language,

painted by Adam Izgin (2021?);

photo by Johannesgabrielsson1, used

under a CC BY-SA 4.0 license (source).3

For if you remit people their trespasses, your heavenly Father too will remit yours; but if you do not remit people, neither will your Father remit your trespasses.

And whenever you fast, do not become gloomy like the impostors, for they obscure their faces so they may appear to be fasting to people; I tell you, ‘amīn, they have received their reward. But when you fast, anoint your head and rinse your face, so you do not appear to people to be fasting, but to your Father that is in secret; and your Father who sees in secret will pay you back.

Textual Notes

a. practicing/to perform (ποιεῖν): The Greek verb here is a broad one with the base meaning “to make” (which, like the Latin facere, came to have many more particular meanings, often in set phrases). I went with “perform” here because it is the root of the term ποιητής [poiētēs], which in turn is the ultimate ancestor of our word “poet,” a sense it did bear already in Greek.

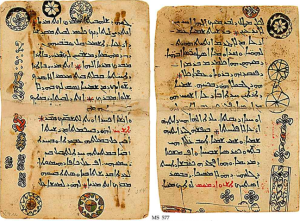

Leaves from MS 577 in the Schøyen Collection,

a Melkite liturgical book written in Syriac

in the eleventh century.

b. Truly/‘amīn (ἀμὴν): In keeping with my preference for transcribing, not translating, Aramaic words as Aramaic when they appear in a Greek text, I replaced the thoroughly Anglicized “amen” with the pronunciation used in Classical Syriac. This is a form of Aramaic that emerged in northern Mesopotamia in the mid-first century; Aramaic had already been an administrative language and lingua franca of the Near East and Central Asia under the Achæmenid Persians [559-330 BC], and continued as such under the Seleucids [312-63 BC] and the Parthians [247 BC-224 CE]. Syriac remains in use as a liturgical language in a few churches to this day, principally in the Near East and India.

c. piety/justice (δικαιοσύνην): The word δικαιοσύνη [dikaiosünē] does mean “justice”4 rather than “piety,” so I’m scratching my head a little at the RSV here. At first I thought it might be a variant in the text itself, but the only one of those that I found (in a non-exhaustive search) replaced δικαιοσύνη with ἐλεημοσύνη [eleēmosünē], which also doesn’t mean piety—see note d for more details. I suppose they may be using it in the sense “honoring of the law” or “observance of custom”? Perhaps this is cynical of me, but I can’t help feeling uneasy at this swerve away from literal translation for a common and pretty simple word, when it happens to be describing giving to the poor in terms of justice rather than of generosity.

d. alms/charity (ἐλεημοσύνην): Neither of these renderings is literal. Ἐλεημοσύνη [eleēmosünē] is derived from the same root as the second word of the phrase Kyrie eleison, and essentially means “mercifulness, pity.” Actual usage had restricted the significance of the word, so “charity” suggested itself as a fairly exact parallel in English.

A tzedekah (“righteousness”) box, of the kind

a synagogue might have for taking alms, made

ca. 1820; now in the National Museum of

American Jewish History in Philadelphia.

e. the hypocrites/the impostors (οἱ ὑποκριταὶ): Here, of course, we run into one of the most recognizable words in the Gospels: hypocrite. Its etymology is fascinating. The Greek ultimately derives from ὑποκρίνομαι [hüpokrinomai], itself derived from a more basic verb, κρίνω [krinō], whose most primitive meaning seems to have been something like “to distinguish, separate.” The secondary verb ὑποκρίνομαι thus came to mean “to interpret” and eventually “to answer,” and from there (given the prominence of dialogue in drama) it acquired the meaning “to play (a role), act (on stage).” Accordingly, actors were known as ὑποκριταὶ [hüpokritai], or ὑποκριτής [hüpokritēs] in the singular.

f. in secret/hidden (ἐν τῷ κρυπτῷ): The Greek here, besides being related to terms like apocrypha, is also the root of the word crypt and its derivatives—including, weirdly, the very Anglo-Saxon-sounding final syllable of the word undercroft.

g. street[s]/broadways (πλατειῶν): The Greek word means “broadways” almost literally. It is from the same root that Plato (essentially, “Brad“) got the nickname we know him by; his birth name was Aristocles.

Part of the fresco The School of Athens

(1511) by Raphael, depicting the father of

Western philosophy, Brad of Athens.

h. room/store-room (ταμεῖόν): This word indicated an interior room generally used for storage, or sometimes (in wealthier homes) as a treasury. The central idea seems to be that it is not a place people inhabit, and therefore one of the few places in a house most likely to be empty, not to mention windowless.

i. heap up empty phrases/blather (βατταλογήσητε): It is probably impossible to be sure, but I have to wonder whether Batta, the name of the gossipy and mean-spirited nursemaid from Till We Have Faces, was inspired by this verb. To the best of my knowledge, βαττα in itself is meaningless in Greek, and serves as a kind of semi-onomatopoeia, very like such English words as “blather.”

j. the Gentiles/those of the nations (οἱ ἐθνικοί): Interestingly, the term here is not “the nations” simply, which would be οἱ ἐθνοί [hoi ethnoi]. Hyper-literally, οἱ ἐθνικοί would be “the nationals” (but without the athletic suggestion that phrase currently carries); slightly closer in sense, but with less racist connotations in Greek, would be “the ethnics.”

k. disfigure … may be seen/obscure … may appear (ἀφανίζουσιν … φανῶσιν): Neither of these translations quite captures the pun in the Greek (though I feel mine suggests it). The verbs here, ἀφανίζω [afanizō] and φαίνω [fainō] are directly related—the former basically is the latter, but with the suffix -ίζω (used to form verbs, equating with our “-ize” or “-ify”) and the privative prefix ἀ-, meaning “un-” or “not.”

As for φαίνω, its primary meaning is “to shine, give light.” From here, it was extended into various forms, many of them about seeing, seeming, appearing, revealing, etc. It is used frequently in the New Testament, both in its basic form and meaning and its many extended meanings; the English words epiphany, phantasm, and phenomenon are all descended from φαίνω (as are some of their more esoteric cousins, like hierophant and phenotype; even phosphorus is related, at a greater remove).

l. anoint your head and wash your face/anoint your head and rinse your face (ἄλειψαί σου τὴν κεφαλὴν καὶ τὸ πρόσωπόν σου νίψαι): Anointing with oil is of course no longer a common element in people’s grooming, but it’s not inappropriate that this sounds a little like “wash your face and moisturize.”

m. secret (κρυφαίῳ): The Greek here [krüfaiō] is an elaborated form of κρυπτῷ from up in note f. I translated the two differently because they are, sensu stricto, different words, but the elaboration functions much the same way it does in English: There is a difference between calling someone “scarred” and “scarified,”5 but it’s fairly minor (indeed, I’d have preferred to use a word a little closer in form to “hidden” if I could have thought of one).

And, yep, two-parter! Next time we’ll discuss the niceties of the Lord’s Prayer.

Footnotes

1The Iconoclasms—there were two: one from around the late 720s until 787, the second from 815 to 843—were periods during which representational art depicting God, Christ, and the saints was forbidden by law in the East Roman Empire. The Iconoclasts, or “image-smashers,” believed that they violated the Second Commandment.2 The contrary party, the Iconodules (“image-honorers”), carried the decision of the Second Council of Nicæa in 787, summoned by Empress Irene shortly after her husband died. Their cause suffered a reversal under Emperor Leo V, but it was then lastingly victorious after the intervention of St. Theodora II. Like Irene’s, Theodora’s husband Theophilus had been an Iconoclast, but after she was widowed and appointed regent for their son, the empress dowager promptly restored the veneration of ikons (an occasion celebrated among the Orthodox to this day on the First Sunday of Lent). However—in a refreshing change of course from Irene—St. Theodora did not have her son blinded in order to keep the throne for herself. It’s the little things, you know?

2The East broadly follows the same enumeration of the Commandments as most Protestants. Catholics and Lutherans use a system set forth by St. Augustine:This treats the Orthodox/Protestant First and Second Commandments as one, and makes “Thou shalt not covet thy neighbor’s wife” the Ninth Commandment, followed by “Thou shalt not covet thy neighbor’s house … or any thing that is thy neighbor’s.” (If you’re looking at Exodus 20:17 and wondering why St. Augustine pulled a phrase from the middle of a sentence out to make an independent commandment, the answer is to turn to Deuteronomy 5:21, which phrases the passage differently.) Both diverge from the usual enumeration in Judaism, which combines the Orthotestant First and Second and the Catholutheran Ninth and Tenth, but includes the preface “I am the Lord thy God” as the First Commandment. The Jewish numbering and content therefore align with the Orthodox/Protestant numbering of the commandments, beginning with the Third (the one about not taking the Name in vain).

3As far as I can tell, this is in the Madnhaya script, mainly associated with East Syriac (the variety once spoken in Iran and Iraq), except the title, which seems to be written in the classical Estrangela script. Judging from what little I’ve read on the subject, the effect, for those familiar with Syriac writing—which I am not!—would be a bit like a blackletter title over a text in a standard Roman font.

4I.e., justice as a personal quality, “law-abiding-ness”; “righteousness” is a good if archaic synonym. As an abstract concept, a trait of impersonal things, or a goddess, the word for “justice” is δίκη or (in the lattermost case) Δίκη [dikē, Dikē].

5Note that “scarify” has the initial vowel of tar, not of bear. I don’t actually know how common this mistake is, but for a long time I assumed that scarify was derived from “scare,” rather than (correctly) associating it with “scar.”