Okay, This Time Shrovetide Really Has Started

First, a little light housekeeping. In my last post, I at first said, incorrectly, that the ninth was Septuagesima Sunday. That day is actually the sixteenth. In the Ordinariates, it is the beginning of the pre-Lenten season of Shrovetide.1 Most of the ritual changes associated with Lent begin in Shrovetide: The color of the vestments and hangings changes to purple; the Gloria is again omitted from the Mass, as in Advent; and (unlike Advent) the Alleluia normally sung before the reading of the Gospel is exchanged for a Tract. (This is still an acclamation of praise, but one without the word “alleluia,” which is not spoken during Lent—solemnities and Maundy Thursday, but not Lenten Sundays, are excepted from this rule.)

Additionally, like the Gloria, the Te Deum (a hymn typically used at Mattins) is omitted from the Liturgy of the Hours, i.e. the formal prayer of the Church outside the Mass.2 The Benedicite Omnia Opera is the standard replacement, though a broader selection of Old Testament canticles can be found in some books, like the Song of Moses or the Prayer of Hezekiah.

Gospel the Third

Because purple is a color linked with mourning,

and due to their leaves being rather sword-

shaped, purple irises are one of the many

flowers associated with the Mother of Sorrows.

Now then! Let’s proceed with Luke. I haven’t done a read-up lately on either St. Luke the person or the corpus attributed to him, i.e. the third Gospel and the Acts of the Apostles; I’ll therefore postpone my attempt at a proper introduction like I did for Mark (and then re-did for Mark), and note only a few traits of Luke’s writing.

- Luke is the longest of the Gospels, nearly twice the length of Mark; it is also the only Gospel to have a follow-up second volume (Acts).

- St. Luke, one of the companions of St. Paul, is the traditionally ascribed author of Luke and Acts; as far as I can tell, this ascription is one modern scholarship tends to accept. St. Luke is generally held to have been a Gentile by birth (tests on his putative relics identify them as those of a Syrian3 from the right time period), possibly one who had converted to Judaism or become a “God-fearer” before the gospel came to Antioch.

- While certainly a Synoptic, Luke is a bit of an outlier, with a significant proportion of unique material. He is our only source for most of the narrative leading up to and surrounding Jesus’ birth, our only explicit source for the Ascension, and the only author to relate several other episodes and a number of parables (like last week’s miraculous catch of fish, or the Parable of the Good Samaritan).

- Given the inter-ethnic difficulties the infant Church had (which led indirectly to the first persecution in Jerusalem) and the controversial Pauline mission to the Goyim, as well as Luke’s own (likely) personal origins, it is not surprising that he is the most “woke” of the evangelists, showing a more pronounced interest in the status of women and the poor than the other three do.

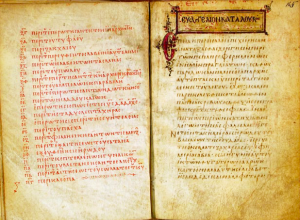

The Sermon on the Plain

The beginning of Luke in the Codex

Petropolitanus, a 9th-c. Greek manuscript

of the Gospels, now housed in the

National Library of Russia.

It is easy to hear Jesus’ words in this Gospel and feel bad that you’ve been remembering the Beatitudes so badly for so long. Well, good news (other than the gospel, I mean): you weren’t. The passage we habitually know by that title is the parallel in Matthew 5, and opens the Sermon on the Mount—but this is the Sermon on the Plain. It records much, though not all, of the same material, some of it in notably different forms.

This seems to distress some Christians, who appear to think that this means Luke and Matthew are contradicting each other. Which one has the right account? But there’s no reason they both shouldn’t have the right account. Jesus was, after all, a teacher; anybody who has ever had to teach anything to anyone can tell you that teachers have to spend an awful lot of time repeating themselves, often with small changes in wording (whether for mere variety’s sake, or to address misinterpretations, etc.) Quite a number of ostensible disagreements among the Gospels can very easily be put down to this—which does not mean there are no puzzling discrepancies in the New Testament, but there’s no need to go putting more into it that aren’t there.

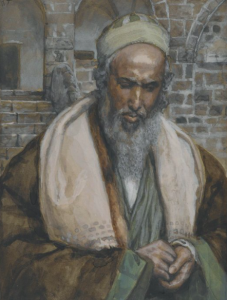

Saint Luke (1894), by James Tissot

It may, therefore, be of value to attend to the differences in wording and content between the Sermons on the Mount and on the Plain. They are presumably there because our Lord the Spirit intended us to have both versions, either because two similar but distinct truths need notice, or for some kind of “binocular vision” of a single truth. (As hitherto, I have marked verses left out of the public reading but present in my translation in grey.)

Luke 6:17, 18-19, 20-26, RSV-CE

And [Jesus] came down with them and stood on a level place, with a great crowd of his disciples and a great multitude of people from all Judea and Jerusalem and the seacoast of Tyre and Sidon, who came to hear him and to be healed of their diseases; and those who were troubled with unclean spirits were cured. And all the crowd sought to touch him, for power came forth from hima and healed them all.

And he lifted up his eyes on his disciples, and said:

“Blessed are you poor,b for yours is the kingdom of God.

“Blessed are you that hunger now, for you shall be satisfied.

“Blessed are you that weep now, for you shall laugh.

“Blessed are you when men hate you, and when they exclude you and revile you, and cast out your name as evil,c on account of the Son of man! Rejoice in that day, and leap for joy, for behold, your reward is great in heaven; for so their fathers did to the prophets.

“But woed to you that are rich,e for you have received your consolation.

“Woe to you that are full now, for you shall hunger.

“Woe to you that laugh now, for you shall mourn and weep.

“Woe to you, when all men speak well of you, for so their fathers did to the false prophets.”

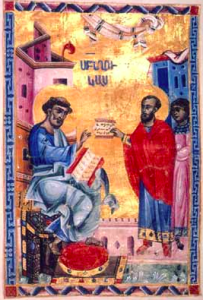

Miniature of St. Luke by the prolific 13th-c.

Armenian illuminator Toros Roslin.4

Luke 6:17, 18-19, 20-26, my translation

And he went down with them and stood on a plain, as did a large crowd of his students, and a large throng of the people from all Judæa and Jerusalem and the seacoast of Tyre and Sidon, who came to hear him and be healed of their sicknesses; and those who were disturbed by unclean spirits were healed; and the whole crowed sought to grasp him, because power came out of hima and healed everyone.

And he raised his eyes onto his students and told them:

“Blessed are beggars,b because the kingship of God is yours.

Blessed are those who are now hungry, because you will be full.

Blessed are those who cry now, because you will laugh.

Blessed are you whenever people hate you, or whenever they exclude you, or reproach you, or cast your name out as onerous because of the Son of Man; be glad on that day and jump for joy, for see, your reward is great in heaven: for their fathers did the same thing to the prophets.

“But woe to you, the rich, because you are far from your consolation.

Woe to you, those who are now satisfied, because you will be hungry.

Woe, you who laugh now, because you will mourn and cry.

Woe, if ever everyone speaks well of you, for their fathers did the same thing to the false prophets.”

Textual Notes

The tympanum of the Church of St. Trophime,

Arles, depicting Christ enthroned with the

Evangelists (St. Luke is the ox). Photo by Rolf

Süssbrich—CC BY-SA 3.0 license (source).

a. power came forth from him/power came out of him (δύναμις παρ’ αὐτοῦ ἐξήρχετο): The description of Jesus’ healings here comes off almost cartoonish (cf. the healing of the woman with the hemorrhage in Mark 5). The same humorous quality persists all the way into the book of Acts—I would point especially to the stories of Rose5 the door-maid and of Eutychus (whose name literally means “lucky”!)

b. Blessed are you poor/Blessed are beggars (Μακάριοι οἱ πτωχοί): The thing I find striking about this part of the Lucan homily is the absence of the phrase “in spirit.” It is simply and straightforwardly about poverty; it is halfway tempting to render πτωχοί [ptōchoi] as “the homeless,” that being the form in which we most often encounter beggary today. My own hunch is that this version was given as a complement to the Matthean version, to keep us from over-spiritualizing the text.

c. as evil/as onerous (ὡς πονηρὸν): This has come up here before, though I don’t recall when: The word πονηρός [ponēros] is conventionally translated “evil” in Koiné Greek (at least in the New Testament); the “evil” we ask to be delivered from in the Lord’s Prayer is an agent or condition of πονηρός-ness. Its root is the verb πονέω [poneō], meaning “to labor, toil, work.” From there, the adjective seems to have passed through early stages of meaning something like “wearisome, oppressive” and perhaps “cruel,” before at last becoming “evil” in the sense of “malicious, wicked.”

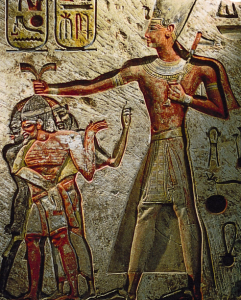

Pharaoh Ramesses the Great (r. 1279-1213 BCE)

taking a Nubian, a Syrian, and a Libyan captive—

one of several suggested Exodus pharaohs.6 (Photo

by Speedster, CC BY-SA 4.0 license—source.)

When I first encountered this development, I just found it an interesting curiosity; I don’t think it occurred to me until now to view it in light of the event that defines Israelite identity in the Hebrew Bible. In Egypt, the evil one from whom God delivered his people was specifically an oppressor, a taskmaster. I’m not certain what light that sheds on this passage—perhaps none—though probably it does shed light on how we’re meant to view evil.

d. woe (οὐαί): The English word and the Greek here are obviously similar, in both form and meaning. In this they are paralleled by Gothic wai, Latin væ, Old Irish fæ, Sanskrit उवे (uvé), Old Church Slavonic ⱆⰲⱏⰹ [uvy], and many others. All are believed to descend from a Proto-Indo-European form, reconstructed as *wóy or something close to it. However, the reconstruction is controversial, and there are scholars who believe “woe” is in reality a Semitic loan, perhaps originating from the Hebrew אוֹי [‘awy] (forerunner of the modern Yiddish “oy”).

e. to you that are rich/to you, the rich (ὑμῖν τοῖς πλουσίοις): Here again—though the parallel is perhaps to be found in the Epistle of James rather than in Matthew—we seem to see a black-and-white equivalence made: “beggars : good :: wealthy : bad.” We do, of course, know that our Lord’s teaching was a great deal subtler than this simplistic dichotomy.

Except, do we?

To be clear, I don’t mean that our Lord was stupid. What I mean is that there is a great deal more intelligence in that “simplistic dichotomy” than most of us wish to allow.

In theory, most of us would admit that a man who has both God and a bowl of ice cream has no more than a man who has only God; but few souls are ever moved by this knowledge to forego a bowl of ice cream. Similarly, one can bleat about temptation and prudence and occasions of sin as much as one likes—the bad fact is that most of us, most of the time, are more interested in what we can get by on than what is best for us (let alone what is worthy of our Creator), and the instant we hear that having a lot of money or possessions isn’t intrinsically a sin, good enough! Brain off, all done. We don’t want to hear about the ways money can warp our judgment and deform our wills. We don’t want to learn what the Church says the point of property is, or why private property7 is simultaneously a genuine right and yet a right with limits that can be overridden. Put bluntly, we want to know enough to make our conscience shut up, and not more.

Our culture treats getting rich as a legitimate goal, and almost as everyone’s default goal (yet we have the gall to moralize about first-century Jews seeing financial success as a sign of God’s favor!). Attaining, and maintaining, the attitude to money and property evinced by the teaching and example of Christ and his Apostles, especially St. Paul, must be expected to be uphill work in a society like that. Add anti-Communism to the mix, which some people are weirdly attached to—I mean, yes, the USSR did fall over thirty years ago; yes, China has ceased to be Marxist in any meaningful sense; no, no other world powers are Communist any more; no, we’re not going to let that have the slightest effect on our anti-Communist fervor—and it begins to make some amount of sense that the conservative wing of Catholicism in the US looks daily more like the American Catholic Church from Walker Percy’s Love in the Ruins.8

Uphill work, yes. But it is not work that we can skip, if we wish to be faithful to the gospel. The alternative is—well, we are informed that seed did fall among thorns. It just didn’t end well.

Footnotes

1Admittedly, this season only lasts seventeen days, and does not have a strongly distinctive character of its own, being directly dependent on Lent. But still, how can you not love that name? “Shrovetide.” So satisfying.

2Unlike the Mass, the Liturgy of the Hours, also known as the Divine Office, is not normally binding on anyone but consecrated religious (in its complete form) and priests (who must say part of it, though not usually the entirety). However, laity are encouraged to pray the Hours or some portion thereof if they wish.

3Syrian may seem like it can’t be right in this context; isn’t Syria one of those post-colonial countries that was kinda made up? Aren’t Syrians just Arabic? The best answer is “Mostly no.” The modern borders of Syria are a relic of colonialism, as the straight lines give away; however, the Syrian people—peoples, really—are far older than French colonialism. The Near East has been home to a range of Semitic nations for millennia, and Europeans have been using term Syrian (originally a truncated form of Assyrian) indiscriminately for most of them, except the Jews, since the early Roman Empire. From Alexander’s conquests to the early Byzantine era (ca. 300-600), we can speak of a “Syro-Greek” or “Græco-Syrian” ethnicity in Anatolia and the Levant, doubtless mixed with other elements—Armenian, Persian, Phoenician, etc. It is from this Roman-imperial “phase” that St. Luke, if he was indeed Syrian, would have hailed.

4The surname Roslin is an oddity, not because it isn’t Armenian (though it doesn’t seem to be), but because it is present; surnames were not the norm in thirteenth-century Armenia except for houses of the nobility, none of which bore that name. Given the period, Roslin may have been the child or grandchild of a crusader: Intermarriage between Armenians and crusaders was not uncommon, especially since the Armenian people, like a few other ethnicities in the Near East, had remained resolutely Christian after the Muslim Caliphate became the dominant regional power. Armenian art historian Levon Chookaszian put forth the intriguing idea that Toros Roslin was descended from Henry Sinclair, a Scottish crusader from Clan Sinclair. The heads of Clan Sinclair were (and are) also barons of Roslin—often spelled “Rosslyn”—and allege that they received this barony from King Malcolm III (r. 1058-1093). If so, this would be in time for Henry Sinclair to take the honorific with him on crusade and perhaps bestow it on a descendant.

5The name is merely transliterated in most Bibles: Rhoda. (It isn’t absolutely certain it means “rose”; it could come from a slightly different word meaning “pomegranate,” or from the name of the island of Rhodes—which itself may mean “roses,” or etc. etc.)

6No pharaoh or period of Egyptian history clearly corresponds to Exodus. This prompts some scholars to dismiss the book as historically valueless, but many still think there is at least an element of genuine memory in it. Ramesses the Great (or Ramesses II) is a common guess thanks to the apparent name-drop in Exodus 1:11. A few others have been proposed. Ahmose I (r. 1550-1525 BCE) was a favorite with several Church Fathers: He expelled the Hyksos, a Semitic group who had taken power as the Fifteenth Dynasty (which is, on hypothesis, why “there arose up a new king over Egypt, which knew not Joseph”—Exodus 1:8). Sigmund Freud famously suggested Moses was an Atenist priest forced to flee the country after the death of Akhenaten (r. 1353-1336 BCE), the “heretic pharaoh” who tried to establish solar henotheism throughout Egypt. I wonder if there’s something in the theory it was Thutmose II (r. 1493-1480 BCE?), the husband of Hatshepsut. When Thutmose II’s mummy was identified (probably) and uncovered, he was found to have had severe health problems in life; Gaston Maspero, the Egyptologist who unwrapped the mummy, stated that his body was “thin and somewhat shrunken, and appears to have lacked vigor and muscular power,” as well as pointing out that “The skin is scabrous in patches, and covered with scars”. Speaking as someone without relevant degrees in biology, archæology, etc. (and therefore open to correction), those things sound like they’re consistent with the remains a guy who lived through a nationwide pollution of the Nile, multiple mass infestations of insects, a catastrophic collapse of the country’s livestock, the shortages that would assuredly result from all this, and a plague of skin-boils.

7In the language of Marxist-anarchist theory, it’s probably more accurate to say that the Catholic Church affirms the legitimacy of personal property and allows for the legitimacy of private property.

8For those not familiar with this uncomfortably prescient novel, its American Catholic Church is a schism from the Roman Catholic Church: It has the Latin Mass, a new festival known as Property Rights Sunday, and a custom of playing “The Star-Spangled Banner” at the elevation of the Host.