“Skip a Bit, Brother”

Brother Maynard (right), accompanied by his

brother, Brother Maynard’s Brother. Image

from the Monty Python Wiki, used under a

CC BY-SA license (edition unspecified—source).

I was honestly quite miffed to discover that the Gospel for this Sunday was not Mark 5.1-20, the next pericope1 in sequence. That passage (especially in combination with this week’s actual text!) builds beautifully on the question last week’s Gospel concluded with: “What kind of man is this, then, that even the wind and the sea listen to him?” There were details I decided to leave out of that post because I thought I’d be covering them this week. Harrumph. Since we won’t be covering it, at least not now, I offer a summary.

Content warning: demonic possession, self-harm

Jesus travels to the Decapolis (a mostly-Gentile region). He there meets a man who had been living in a necropolis2 and cutting himself, who is possessed by the now-notorious devil, or group of devils, Legion. Like many demons in Mark, it identifies Jesus as the “Son of the Most High God.”3 Jesus promptly moves to exorcize the man. Legion begs to be allowed to go possess a nearby herd of a couple thousand pigs, rather than be sent “out of the country” (I’m not clear whether this fear is literal or a euphemism; in the parallel passage in Luke, the devil begs not to be cast into “the deep”). Jesus allows this; the pigs rush off a cliff and drown; and the locals are extremely freaked out and ask him to leave, probably thinking he was a powerful Jewish sorcerer. The ex-demoniac asks to be allowed to come with Jesus as he and the apostles are leaving, but Jesus tells him to go home to his family instead.

A medieval illumination of the exorcism of

Legion (and also a terrific example of

medieval illuminators just really liking to

have a little dude, a li’l guy).

We pick up in verse 21. Jesus returns to the side of the Sea of Galilee that he just left, and thus to Jewish turf. (His landing place goes unspecified, and may have been in a number of places, but the likeliest candidate is probably Capernaum: it’s the place he just left and his informal Galilean HQ.)

Daughters

Okay, but what’s with the “daughters” stuff, in the title and in this section title? (you ask, not having caught on yet that I have a habit of putting shamelessly convenient questions in your mouth in these posts. Maybe work on your situational awareness.)

I feel like there’s something going on in this passage that I’m not quite catching; it’s got several quirks and atypical details I don’t fully understand. It’s the only instance I can think of in which Jesus performs a miracle “incidentally,” while on his way to perform another; and these two miracles are linked in a few other small ways. Both are performed for women, though neither woman directly requests them. The one miracle cures a “flow of blood” (perhaps menorrhagia, i.e. excessive menstrual bleeding, a symptom of a few different ailments) which has lasted twelve years, while the other resurrects a twelve-year-old girl. Both miracles also show a great sensitivity on Jesus’ part to the multivalent nature of publicity: i.e., not only how unpleasant and unwelcome it can be, which fits in very comfortably with Mark’s accent on secrecy, but also how good and necessary publicity can be under the right circumstances.

Mark 5.21-43, RSV-CE

And when Jesus had crossed again in the boat to the other side, a great crowd gathered about him; and he was beside the sea. Then came one of the rulers of the synagogue,a Jairusb by name; and seeing him, he fell at his feet, and besought him, saying, “My little daughterc is at the point of death. Come and lay your hands on her, so that she may be made well, and live.” And he went with him.

A set of tzitziyot, the tassels that adorn

a Jewish prayer shawl. Note the rich blue,

mandated by Numbers 15.

And a great crowd followed him and thronged about him. And there was a woman who had had a flow of bloodd for twelve years, and who had suffered much under many physicians, and had spent all that she had, and was no better but rather grew worse. She had heard the reports about Jesus, and came up behind him in the crowd and touched his garment.e For she said, “If I touch even his garments, I shall be made well.” And immediately the hemorrhage ceased; and she feltf in her body that she was healed of her disease. And Jesus, perceiving in himself that power had gone forth from him, immediately turned about in the crowd, and said, “Who touched my garments?” And his disciples said to him, “You see the crowd pressing around you, and yet you say, ‘Who touched me?’” And he looked around to see whog had done it. But the woman, knowing what had been done to her, came in fear and trembling and fell down before him, and told him the whole truth. And he said to her, “Daughter, your faith has made you wellh; go in peace, and be healed of your disease.”

While he was still speaking, there came from the ruler’s house some who said, “Your daughter is dead. Why trouble the Teacher any further?” But ignoring what they said, Jesus said to the ruler of the synagogue, “Do not fear, only believe.” And he allowed no one to follow himi except Peter and James and John the brother of James. When they came to the house of the ruler of the synagogue, he sawj a tumult, and people weeping and wailing loudly.k And when he had entered, he said to them, “Why do you make a tumult and weep? The child is not dead but sleeping.” And they laughed at him. But he put them all outside, and took the child’s father and mother and those who were with him, and went in where the child was. Taking her by the hand he said to her, “Talitha cumi”l; which means, “Little girl,m I say to you, arise.” And immediately the girl got up and walked; for she was twelve years old. And immediately they were overcome with amazement. And he strictly charged them that no one should know this, and told them to give her something to eat.

Mark 5.21-43, my translation

Ruins of an ancient synagogue in the north of

modern Israel (used under a CC BY-SA

3.0 license—source).

And when Jesus had crossed over again in the boat to the far side, a large crowd gathered before him, and he was beside the sea. And one of the synagogue headsa came, Yairb by name, and on seeing him falls at his feet and appeals to him at length, saying that “My little girlc is at her last hour, so come and lay hands on her, so that she may be saved and live.” And he went with him. But the large crowd followed with him, and pressed him.

And a woman who had had a hemorrhaged twelve years, and suffered many things from many doctors and had spent everything she had (and none of it had been any use—rather, she had gotten worse), hearing about Jesus, came in the crowd behind him and laid hold of his cloake; for she said that “If I can just lay hold of his cloak, I will be saved.” And right away the spring of her blood was dried up, and she knewf in her body that she was healed of her affliction.

And right away, Jesus perceived within himself that power had gone out of him; turning around in the crowd, he began saying: “Who laid ahold of my clothes?” But his students said to him: “You look at the crowd pressing you, and you say ‘Who laid hold of me’?” But he looked around to see whog had done this. So the woman, frightened and trembling, knowing what had happened to her, came and placed herself before him and told him the whole truth. So he told her: “Daughter, your faith has saved youh; go in peace, and in good health without your affliction.”

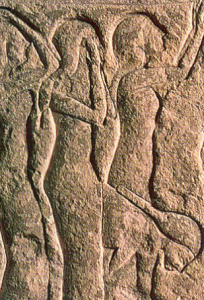

Detail of an Egyptian relief depicting four

mourners (date unspecified). Note that

one of the four women is stooping, to

gather dust to throw on her head.

While he was speaking, people came from the synagogue head’s, saying that “Your daughter has died; why bother the teacher anymore?” Jesus overheard what they were saying, and told the synagogue-ruler: “Do not be afraid, only believe.” And he did not permit no one to follow with him,i except Rocky and Jacob and John, Jacob’s brother.

And they came into the house of the synagogue-ruler, and he beheldj a commotion and much crying and keeningk; coming up to them, he said to them: “Why are you making a commotion and crying? The child has not died, but lain down.” But they laughed at him. He cast them all out, taking with him only the father of the child and her mother and those with him, and proceeded to where the child was; and taking hold of the child’s hand, he told her, “Talitha koum“l (which, interpreted, is “Young lady,m I tell you, get up”). And right away the young lady stood up and walked around, for she was twelve years old. And they were astonished, right away greatly beside themselves. And he charged them emphatically that no one should know about this, and told them to give her something to eat.

It doesn’t say he didn’t suggest stuffed

grape leaves (photo by Andy H. M., used

under a CC BY-SA 4.0 license—source).

Textual Notes

a. rulers of the synagogue/synagogue heads: These are translations of a Greek term, ἀρχισυνάγωγος [archisünagōgos], which is itself a translation of the Hebrew רֹאשׁ הַכְּנֶסֶת [ro’sh ha-k’neseth], “head of the congregation.” I gather that this office is roughly continuous with that of a gabbai (also known as a shamash), which I again gather is roughly equivalent to the office of a verger or sexton.4 However, the small amount of research I was able to do suggested that the office of gabbai can vary a good deal from one Jewish community to another, and often embraces liturgical functions as well, at least as a sort of back-up lector.

b. Jairus/Yair: Yair is the original Hebrew form of the name. I’ve taken a guess that it was the man’s own name, but it bears remembering that this is a guess: there were Jews whose native language and/or personal names were Greek in the first century, even in the Levant—the Hebrew-Aramaic idiom is a much safer bet, but it is a bet. If Yair were a native Greek-speaker, then his name might more properly be “Jairus” (well, “Iairos,” but you get the point).

c. My little daughter/My little girl: The Greek here does not ultra-literally say “little girl” or “little daughter”; I went with “little girl” as the more idiomatic expression in English (which was maybe bending my own rules—anybody would think I can’t make up my mind or something). What the text actually uses is a diminutive form of θυγάτηρ [thügatēr] (the normal word for “daughter”), θυγάτριον [thügatrion]. An ultra-literal equivalent would be something like “daughtlerling” or “daughterlet.” (A little amusingly, diminutives in Greek, including this one, are typically neuter, regardless of sex.) This intrigues me, because when Jesus identifies the woman he heals of a hemorrhage on the way, he addresses her as θυγάτηρ. It’s hard to avoid the impression that these two words were chosen to get us to compare the recipients of these two miracles, and also thus distinguished so we wouldn’t mix them up.

d. flow of blood/hemorrhage: “Flow of blood” is the more literal translation here. I decided to go for a slightly more idiomatic translation because, as I touched on above, this text sounds to me like this woman had a persistent, excessive loss of blood, possibly due to something like adenomyosis (caution: pictures) or endometrial cancer (caution: also pictures). The phrase “flow of blood,” on the other hand, in isolation, just kind of sounds like she was having her period. Of course, the RSV then immediately goes ahead and uses “hemorrhage” when the literal translation is simply “blood,” and frankly, I give up.

e. garment/cloak: You may have heard that the Greek here indicates that the young woman here was specifically reaching for the tallith, the blue tassels on Jesus’ prayer shawl! Well, first of all, that’s not what tallith means: tallith is the word for the prayer shawl—the tassels are called tzitziyoth (tzitzit for a single one). And as Tobias Fünke put it, “second’vely,” this also isn’t what the Greek word, ἱμάτιον [himation], meant. A ἱμάτιον was just a cloak or outer garment; to my knowledge had absolutely nothing to do with the tallith. It is perfectly possible that the part of Jesus’ clothes the woman brushed against was a tzitzit, and in fact the parallel passages in Matthew and Luke make it more likely,5 but Mark has nothing to say about it.

A photo of some tzitziyoth is shown above,

below the first paragraph of the RSV

translation. This is a photo of a tallith.

f. felt/knew: From an etymological point of view, the distinction here is fine to the point of negligibility. I went with “knew” for reasons of tone. (If you’d like to read more about the meanings hovering in this general range, I suggest reading C. S. Lewis’ Studies in Words, ch. 6: “Sense.”)

g. to see who: This may merely be the author’s word choice with benefit of hindsight, and thus, insignificant; nevertheless, I’m struck by the word we here translate as “who” (in Greek it’s a form of the definite article, which is a much more “load-bearing” word in Greek in general). The reason I’m struck is not that the word is unusual—on the contrary, it’s as common as dirt—but that, rather than the default masculine form, which in Greek (and in English until recently) did double-duty for what’s called the common gender,6 it is specifically feminine. This may mean that even before he knew who it was specifically, Jesus was looking for a woman.

Either way, this seeking out of the person he had unwittingly healed is also part of this healing. (I’d be happy to credit the source I first found this point in, but unfortunately I have entirely forgotten it.) The following notes are tentative—they’re implications that I think I’m correctly drawing out, but they are not directly present in the text, so please take them with that grain of salt.

- Jesus addresses her with θυγάτηρ, rather than γύναι [günai] as we might expect (which equates to “ma’am”7). This may indicate that, while an adult, she was a relatively young woman; if her issue began at or near puberty (as a menstrual disorder might), she’d be in her early twenties.

- She “had spent everything she had”; this may suggest she was a woman of independent means. This was not common in the ancient world, but there were businesswomen back then as well as businessmen: e.g. St. Lydia in Acts 16, the “seller of purple” (which might mean she sold purple cloth or that she sold the dye itself).

- That phrase also may indicate that she was an adult orphan, probably without siblings, and almost certainly unmarried.

- Women normally could not own substantial amounts of property or money and had to operate under their father’s or husband’s oversight. If her father were alive, one would expect him to be footing the bill for an unmarried daughters’ medical needs; if she were married, her husband would be doing the same thing.

- However, if she was an orphaned only child, her parents might have left her a complete inheritance; this too would be unusual but by no means unheard of. But why specifically an only child?

- If she had any brothers, they would normally receive the entirety of any inheritance, to the exclusion of all daughters (except for any dowry settled on them). If she had only sisters, they might have the inheritance divided between them, if it wasn’t assigned instead to more distantly related males of the family. But she’d be hard pressed to live off an inheritance and spend twelve years unsuccessfully seeking help for her chronic medical condition, even if she didn’t have to divide the inheritance with any siblings.

- Remember that under the guidelines of the Torah, a person of either sex who experienced any kind of discharge was normally “unclean till evening.” And blood was particularly impure. The “flow of blood” could have been a lot of things that cause abnormally long menstruation; some of the conditions which include such bleeding as a symptom can easily go on for half a month—or, since “spotting” is absolutely going to count as a discharge of blood, almost continuously.

- Think for a moment about the centrality of the Temple (which you need to be ritually clean to enter). Now think about the gossipy nature of small working-class towns. Now recall the importance of family connections in a world where most marriages are arranged, and how practically and religiously important fertility is in this culture. We’ve already established that this woman probably wouldn’t have been married, despite being of marriageable age; what do you think her odds are of ever getting married, with this complex of problems? And if she is an orphaned only child—even if the businesswoman possibility above is correct and she’s the girlbossingest first-century Jewish woman who ever girlbossed—what do you think her future looks like, as what I’m totally super sure no one would rudely call “not even real a widow”?

This healing is only half-complete until it is a publicly established fact. Jesus therefore makes a point of seeking her out, both to reassure her that he isn’t angry with her, and to establish her reintegration into the normal life of her community, possibly even to reopen her marriage prospects.

h. made you well/saved you: I believe I’ve complained before that the Greek verb σῴζω [sōzō] means both “to heal” and “to save” and therefore has no really satisfying translation in English. Of the two, I think “save” is marginally less unsatisfying, but (since it’s been a bit since the matter came up) I wanted to make a note of it.

i. he allowed no one to follow him/he did not permit no one to follow with him: The sound of this is that at this point, he actively dismissed the crowd. Note the contrast with the previous miracle, and the tender courtesy with which Jesus sees to it that this girl’s parents, whose nerves are doubtless completely fried already, and are about to get an even bigger shock—a happy shock, yes, but a shock!—will get some quiet time alone with her, before they need to deal with any gawkers.

j. saw/beheld: The verb used here, θεωρέω [theōreō], is slightly uncommon; it can have philosophical implications (it is in fact related to the word “theory”). “To contemplate” would have been an ideal rendering, but I couldn’t think how to fit that into this context in a way that wasn’t horribly awkward.

k. wailing loudly/keening: Here, I’ve taken a pronounced liberty in translation. To explain why, we should first note another thing too commonplace to even mention in the ancient world, but has vanished so completely from much of the modern world that the very idea often baffles people. The weeping and wailing seem to contrast pretty sharply with the statement that “they laughed at him” (unless a sort of incredulous scoff is meant)—that is, unless these people were hired mourners. This was a standard element of ancient funereal practices; being a hired mourner was literally a career.

Now. The cry they were making is described with the verb αλαλάζω [alalazō], which originally described a war-cry,8 and of which the most literal rendering would be “to ululate.” The disputable choice I’ve made is to translate this verb as “keening.” This is one of the rare words that English has borrowed from the Irish language. Caoin (pronounced “keen”) does mean “to cry, weep”; more importantly, caoineadh (roughly pronounced “keen-yuh” … obviously) is a word for a specific type of sung elegy, which until the mid-to-late eighteenth century was a normal element in Irish and Scottish funerals (and may not be quite extinct even today). The so-called “scream” of a banshee is, in reality,9 supposed to be her caoineadh for a deceased member of the family she attends. Ululation in general is a pretty common cultural phenomenon, and it does have parallels in the Near East, North Africa, ancient Rome, etc.; the modern forms of it that I could find tend to be joyful rather than elegiac, and the war-cry meaning seems to be cross-culturally quite frequent too, at least historically speaking. I’m therefore not sure that what these mourners were doing really was similar to keening, but, when I saw the possible parallel, I simply couldn’t resist.

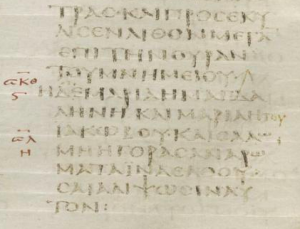

l. Talitha cumi/Talitha koum: So. My version is technically more faithful to the more likely form of the text of Mark; however, it turns out (and I find this hilarious) that the RSV’s version is both more technically accurate to the Aramaic and probably still wrong? Or, well, less correct, not exactly wrong—let’s unpack it.

One feature of many Semitic languages that English-speakers tend to be quite unprepared for is the gender of their verbs. Yes, gender, and yes, verbs. We are used to pronouns having gender, and most of us know that nouns and even adjectives are gendered for speakers of many other languages (including English’s closest kith and kin, like French, German, and Spanish). Some Semitic languages, including both Hebrew and Aramaic, extend this system to verbs, which take on a gendered ending based on the gender of the verb’s subject.10

The Aramaic word for “rise” was qûm, and a masculine imperative would use this unmodified form, whereas when addressing women, the feminine ending –î would be added: thus qûmî, or in typical Roman style cumi. However, in popular speech, it was common to drop the –î and so conflate the feminine and masculine imperatives11—according to an unsourced claim in Wikipedia, at least. (Which, yes, cringe; still, dropping final vowels is a common phenomenon in many languages, so it’s not prima facie ludicrous … my favorite standard for evidence.) This would mean that the original text probably had κουμ [koum]. This is in fact found in the older and better manuscripts of Mark, and presumably represents a phonetic transcription of the Aramaic actually spoken at the time.

The opening page of Matthew in the

Lindisfarne Gospels (created ca. 690).

Meanwhile, κουμι [koumi] could have emerged as a “correction” by a copyist, one who was familiar with the older and/or written distinction between feminine and masculine imperatives. Changes this small were exceedingly easy to make—partly because they’re the sort you can make without even fully noticing you’ve changed anything.

m. Little girl/Young lady: I have taken another, smaller liberty here. The Aramaic talitha is apparently simply the feminine form of the adjective meaning “young,” so whatever noun we choose to insert, it will be an insertion. The Greek translates talitha with the term κοράσιον [korasion], a diminutive, like θυγάτριον above, but derived from the term κόρη [korē], which meant “girl” or “maiden.” Now, when compared with the language of poets like Sophocles or philosophers like Aristotle, Koine Greek was relatively worn down in its ability to express fine shades of meaning, but it’s possible that this word carried a faintly formal aura: Kore had long been and still was a frequent title for the goddess Persephone (albeit strictly in her springtime or “vegetative” aspect12—when worshiped as the queen of the dead, Persephone was not addressed as Kore). If so, then here again, we see Jesus making a point of being courteous. I therefore felt “young lady” conveyed the tone fairly well: true, the phrase can be one of rebuke, but it is also a respectful form of address. (Contrast with the equivalent “young man,” which is all but invariably a reprimand!)

Footnotes

EDIT: In the version of this post originally published, I accidentally swapped footnotes 2 and 3. Apologies for any confusion!

1A pericope, in the field of New Testament studies (especially Gospel studies), is a single coherent unit of narrative. Thus, for example, “Christ’s life before his baptism” is too broad to constitute a pericope (unless nothing more than a brief summary is being given), but “Christ’s nativity” and “Christ’s circumcision and naming” are both pericopes—Matthew and Luke both have the first, only Luke specifies the second.

2If you haven’t come across the term necropolis before, think “graveyard, but Halloween Town levels of theatrical about it.”

3In so doing, it provides both the answer to the question we ended with last Sunday, and the answer that St. Peter is soon going to give to Jesus’ inquiry about whom the apostles think he is.

4In the English tradition, vergers are, or were, responsible for the material care of the grounds and vessels of a church; they are so named because in processions they were entitled to carry a virge, or wand, as the emblem of their office (from which they are also called wandsmen). Sexton was originally a near-synonym, derived, via different intermediaries, from the same root as sacristan. It has since come to connote more specially the duty to oversee the churchyard and its, ah, contents.

5Matthew and Luke both specify that she touched the κράσπεδον [kraspedon] of Jesus’ cloak, a word that means “hem” or “fringe,” but can also be interpreted “tassel,” which could obviously indicate a tzitzit.

6The common gender is a device used in certain languages (German, for instance) that have grammatical gender, indicating an entity that is animate (and therefore not really neuter) but is not, or not exactly, masculine or feminine (mixed groups or the generic “they” are good examples).

7Technically the word γυνή [günē]—the form γύναι was used only in direct address—simply means “woman” or, sometimes, “wife.” In English, using “woman” in direct address normally has a slightly derisive or comical tone, but the same was not true in first-century Greek; it was a perfectly polite form of address for any female adult, provided she didn’t have a noble or religious title that needed to be used instead. (To take a famous example, Jesus addressing his Mother as “woman” in John 2.4 is curious for other reasons, but it was not insulting.)

8There is an unrelated text that nonetheless tickles my fancy here. In Æschylus’ play Agamemnon (stay with me!), when Agamemnon comes home victorious from the Trojan War, his wife—who has been planning to murder him: she’s still mad about that “you tricked me into letting you kill our daughter” thing from ten whole years ago; real grudge-holding type of woman—talks him into walking into the palace on a purple carpet. The value of purple dye back then was so high, this qualified as an act of impious hubris, which invokes the gods’ wrath upon him and virtually guarantees her plan will succeed. She then utters the cry “Eleleu, eleleu!” (the direct form that αλαλάζω and “ululate” half-imitate); onlookers within the play would take this as a standard victory cry celebrating his return from Troy, while the queen (and the real-life audience, who already know the story) know that it is her victory cry over him.

9Not that banshees, or the Good Folk in general, really exist. Obviously they don’t. Besides, they aren’t to be trusted.

10Endings in –t or –i, whether in verbs or not, frequently indicate the feminine in Hebrew and Aramaic; I know the same is true (at least about –t) in Egyptian. I can’t speak to the rest of the show’s lore about them, but in Penny Dreadful, the fact that the names of its sinister Egyptian god-goddess pair are Amun-Ra and Amunet is thus a striking example of accuracy in detail.

11Apparently even Jesus used pronouns now. Or didn’t? “The gender ideology always ye have with you”? I dunno, I’m tired.

12This is probably the origin of the name Cora.