Witnesses

Not officially, but by informal custom, Trinitytide is divided into five parts. The first corresponds to the “Apostles’ Fast” observed in the East; the second lasts until Assumption (15 Aug.); the third, colloquially called “St. Michael’s Lent,” runs till Michaelmas Eve (28 Sep.); the fourth, “Hallowtide,” runs from Michaelmas until All Saints’ Day (1 Nov.) inclusive; and the fifth, “Doomtide,” runs from 2 Nov. (All Souls’ Day) until the beginning of Advent and the new liturgical year.*

This week sees the first part of the long Trinity season conclude. The transition is marked by two solemnities: the Nativity of St. John the Baptist on the 24th, and the martyrdom of SS. Peter and Paul the Apostles on the 29th.

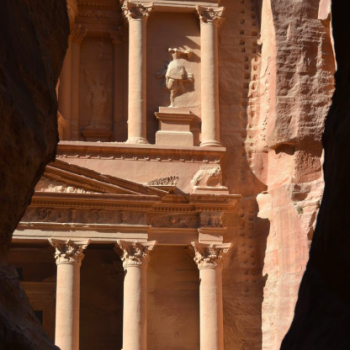

The apse of the papal cathedra in the Lateran

basilica (dedicated to St. John the Baptist).

Photo by Wikimedia contributor Tango7174,

used under a CC BY-SA 4.0 license (source).

First, St. John the Baptist, also known as St. John the Forerunner. For some reason, he is a less popular saint in the West than he used to be; we tend to assume that “Saint John” without specification means the Evangelist, but in antiquity and the Middle Ages, the Baptist would be a safer bet. He is one of several figures whose significance in the economy of salvation is as much “structural” as it is a matter of personal holiness (St. Peter and the Mother of God are also prominent in this category). According to Luke 1.36, he was about six months older than Jesus, who was some type of cousin of his—the relation between the Virgin Mary and St. Elizabeth is not made entirely clear in the text, only that they are relatives. Accordingly, his birth is celebrated at the opposite “end” of the year from Jesus’ own, placing it right around the summer solstice, which in the Medieval period and the Renaissance was known as midsummer.**

Then, on the far side of the Cross, we find St. Peter and St. Paul—the After-runners, if you will. St. Peter, of course, was not only an apostle, but the leader of the pack and part of Jesus’ innermost circle, crucified like his Savior; St. Paul was formally appointed the head of the Gentile mission that soon became (and has remained) the majority of the Church’s membership, and rendered eligible for the apostolate by a unique Resurrection appearance of Christ.

The Apostle Peter Released from Prison

(1371), by Jacopo di Cione, photographed

by Francis Helminski

The astronomical symbolism here is noteworthy: Pentecost falls some time in May or, at latest, early June, meaning that the Holy Ghost descends in fire while the sun is still “waxing” and the days lengthening, and the first movement of Trinitytide reaches a conclusion at midsummer with the nativity of the prophet who foretold that Jesus “will baptize you with the Holy Ghost and with fire,” and the martyrdom of “the two candlesticks standing before the God of the earth.”

Into Trinitytide II

I’ve spent some little time trying to discern the distinctive pattern or character of the second chunk of Trinitytide, which lasts just shy of seven weeks (forty-six days, if I’ve counted correctly); I believe I’ve hit on something, at least tentatively. Its most eminent celebration and only solemnity falls on its very last day, the Assumption of the Mother of God; second to that, it includes the Feast of the Transfiguration (6 Aug.) and the feasts of St. Thomas the Apostle, St. Mary Magdalene, and St. James the Greater (3, 22, and 25 July, respectively). It also begins on 30 June, which, when it does not fall on a Sunday as it does this year, is the memorial of the first martyrs of the Church of Rome.

These might indicate that this is—in some specialized sense—a season devoted to faith, and particularly faith in the face of death. St. James the Greater, in addition to being one of the saints present at the Transfiguration (which was a prophecy of the Passion), was the first of the Twelve to be martyred. St. Thomas’ doubt of the initial Resurrection, as reported by St. Mary Magdalene, is well known, but what is less known is the tradition that he was also late to say goodbye to the Virgin at her death, and that it was for his sake that the apostles opened her tomb—to find, once again, that the body they had expected was gone.

Ivory plaque depicting the Dormition of the

Virgin, late 10th-early 11th cent. Photo by

Wikimedia contributor Clio20, used under a

CC BY-SA 3.0 license (source).

What other meanings may be at work in this stretch of the calendar, I can’t say. I’ll keep thinking.

*If there are any conventional nicknames for the first and second parts of Trinitytide, I don’t know them.

**The tradition of assigning the start of the four seasons to the solstices and equinoxes (approximately 21 Dec., 20 Mar., 21 Jun., and 22 Sep.), while defensible, is somewhat modern. Many ancient cultures observed the cross-quarters instead, these being the midpoint dates between a solstice and an equinox: roughly, these are 1 Nov., 2 Feb., 1 May, and 1 Aug. (and no, it is not a coincidence that Halloween and Groundhog Day mark out the “old-style” winter). This accordingly made the solstices and equinoxes the midpoints of each season—hence the tradition that Jesus was born “in the bleak midwinter,” which doesn’t make sense at all on our calendar.