A Good Thing Came Thence

A mosaic depicting Nazareth in the former

Chora Church (now the Kariye Mosque)

in Istanbul, Turkey.

This gospel is both shorter and simpler than average. Accordingly, if I get the chance to, I’m hoping to translate this week’s epistle as well (II Corinthians 12.7-10, a fascinating passage)—no promises!

Mark 6.1-6, RSV-CE

He went away from there and came to his own country;a and his disciples followed him. And on the sabbath he began to teach in the synagogue; and many who heard him were astonished, saying, “Where did this man get all this? What is the wisdom given to him? What mighty works are wrought by his hands! Is not this the carpenter,b the son of Mary and brotherc of James and Josesd and Judas and Simon, and are not his sisters here with us?” And they took offense at him.e And Jesus said to them, “A prophet is not without honor, except in his own country, and among his own kin, and in his own house.” And he could do no mighty work there, except that he laid his hands upon a few sick people and healed them. And he marveled because of their unbelief.

And he went about amongf the villages teaching.

Mark 6.1-6, my translation

And he left there and went to his hometown,a and his students follow him. And on the sabbath he began to teach in the synagogue; and many listening were shocked, saying: “Where did this man get these things, and who taught him wisdom, and these kinds of powers that come through his hands? Isn’t this the artisan,b the son of Mary and brotherc of Jacob and Joed and Judah and Simon? And aren’t his sisters here among us?” And they stumbled on his account.e But Jesus told them that “No prophet is dishonored, except in his hometown and among his relatives and in his household.” And there he could not do no work of power, except that putting his hands on a few sickly people he healed them; and he was amazed by their unbelief.

And he made a circuit off the villages, teaching.

Nazareth today

Textual Notes

a. country/hometown: Strictly speaking, the literal translation here is “fatherland.” However, that word is generally quite elevated in English, and it also normally indicates a country as a whole, rather than somewhere local and particular (the slang sense of “crib” actually isn’t far off here). I therefore opted for a more idiomatic rendering.

b. carpenter/artisan: “Carpenter” is a normal meaning of the Greek word here, τέκτων [tektōn]. However, it is also applied more broadly, so I decided on a broader term; “craftsman” would have been another option.

I even toyed momentarily with “mason,” before

deciding that that might be a li’l too spicy.

Photo by Rwendland, used under

a CC BY-SA 4.0 license (source).

c. brother: Oh boy. Another text that prompts discussion of the Perpetual Virginity of Mary. My favorite.

The reason I’m making the in-writing equivalent of a grimace is, this is one of those subjects that provokes an avalanche of bad and/or bad-faith arguments, from partisans of both perspectives, and the worst part is, this text neither helps nor hurts either of them. On the Catholic side,* I’ve read apologists arguing that, because ἀδελφός [adelfos] hyper-literally means “of the same womb,” it therefore means only that someone called your ἀδελφός has to have a female ancestor in common, which … wow; I don’t know what you smoke to make that a plausible interpretation, but I’m just saying, it’s selfish not to share.

I’ve also occasionally come across the claim that ancient Greek didn’t have a word for “cousin” and used ἀδελφός instead. This is not true: ἀνεψιός [anepsios] is the ancient Greek word for “cousin.” But this may just be a garbled recollection of the claim that Aramaic has no distinct term for “cousin,” and/or that the translators of the Septuagint habitually used ἀδελφός to refer to cousins in translating the Tanakh. As far as I can tell (I am not up on my Semitic languages!), these two claims are true—not that they prove that these weren’t Jesus’ literal (half-)brothers.

The Marriage of the Virgin (1435)

by Michelino da Besozzo.

Meanwhile, on the Protestant* side, not only are we to ignore the casual or metaphorical use of “brother” known in both Greek and English, we’re apparently also meant to forget about the existence of step-siblings. Divorce was, of course, rarer back then, but spousal death was a lot more common (from all causes, but especially in childbirth), meaning there would have been plenty of step-family to go around. The second-century Protoevangelium of James—one of the “infancy gospels,” works that purport to tell the story of the Nativity in greater detail (and often throw in further backstory about the Mother of God, just for funsies)—actually states positively that the “brothers of Jesus” were stepbrothers, children of St. Joseph by a previous marriage, which remains the standard view among the Eastern Orthodox. Of course, the Protoevangelium of James is not inspired Scripture. But frankly, if we’re weighing who’s likelier to be correct, and the choices are

- pious author who lived in the same culture and spoke the same language within a couple centuries of the events he’s writing about, or

- equally pious author who lived another eighteen centuries later, thousands of miles away, and had none of the cultural or linguistic advantages of the first guy,

I would put my money on the first guy. And that’s before asking whether the Christians of the second guy’s culture and time period had a strangely widespread and markedly unbiblical unfriendliness toward celibacy.

In sum, this text is no proof for either view, and everybody is being annoying about nothing. Stop it.

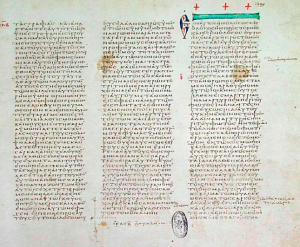

A leaf from Codex Vaticanus, one of the

earliest and most important uncial

manuscripts of the Gospels, showing the

end of Luke and the beginning of John.

d. Joses/Joe: In using “Joe,” I may have crossed the thin line separating “colloquial” from “casual”; I simply couldn’t figure out how else to convey the relationship between Ἰωσῆς [Iōsēs] and Ἰωσὴφ [Iōsēf]: the former is apparently an adaptation of the latter. The name Ἰωσὴφ is indeclinable** in Greek; Ἰωσῆς (with the stem Ἰωσῆτ- [Iōsēt-]†) is an alternate form that does decline normally. (I’m a little surprised an adaption like Ἰωσῆψ [Iōsēps] wasn’t used, which would have allowed the stem to be Ἰωσῆφ- quite neatly; maybe it looked too similar to Ἰωσὴφ to conveniently distinguish the two. Or, who knows, maybe people just thought Ἰωσῆψ sounded stupid.)

e. took offense at him/stumbled on his account: Here we have a verb, σκανδαλίζω [skandalizō], that is neither difficult inherently nor wholly unfamiliar to our day and age, but which—thanks to its relationship to derived terms in English, some of which have theological weight—is an unbelievable pain in the neck to translate. (There are a few of these; believe it or not, the word “priest” is another.) Let’s get into it.

In ancient Greek, a σκάνδαλον [skandalon] is a snare or tripwire; by extension, it can refer to traps in a general way, or anything people are prone to trip on, like ill-placed rocks on a footpath. The term thus comes to mean “cause of stumbling,” “cause of an offense,” or “cause of transgression,” perhaps due to (or just with reinforcement from) the fact that both the Torah and the teaching of Jesus are treated and described as “ways.” It is for this reason that scandalum in Latin and “scandal” in English assume the meaning that they’re given in Catholic moral theology:

Scandal is an attitude or behavior which leads another to do evil. The person who gives scandal becomes his neighbor’s tempter. … They are guilty of scandal who establish laws or social structures leading to the decline of morals and the corruption of religious practice … This is also true of business leaders who make rules encouraging fraud, teachers who provoke their children to anger, or manipulators of public opinion … [or] anyone who uses the power at his disposal in such a way that it leads others to do wrong[.] —Catechism of the Catholic Church §§2284, 2286-2287

So far, so straightforward. Like I said, “cause of an offense” isn’t that complex an idea: there are such things as offenses against right conduct, and those acts, like all acts, have causes. What’s the issue?

Byzantine ikon of the blasting of the fig tree.

Well, that word “offense” is kind of the issue, because it’s got two related but very different senses. “An offense” is a transgression of some kind; this is what I’m going to call the objective sense of the term. It’s different from feeling angry or indignant about something, i.e. “taking offense” or “being offended”—which I’ll call the subjective sense. The objective sense is referring to a deed done by someone, in the world of social interactions. Subjective-sense offense, however, is a response, within a person: it may show up in that same world of social interactions, e.g. as a judgmental look on someone’s face, but it is not the same kind of thing as an objective-sense offense. “Transgression” is a really useful word here, because it’s a synonym only for the objective sense; you can’t say that a group of religious people who saw a lewd public display were “transgressed by it,” only that they were “offended by it.”

The distinction is important. Self-righteous types will tend to take everything that they find offensive (subjective sense), and make it out to be the sin of scandal (objective sense), on the grounds that, look, there is “offense.” This is a form of equivocation that slips under most people’s radar, and it facilitates all kinds of artificial standards of conduct. The only reason I ever caught it is that I’ve had to spend years dealing with bad-faith arguments about how using LGBT terms “gives scandal”—even though the supposedly problematic meanings of the terms in question are being imposed by the very people who claim to be thus scandalized.

Can I just say, I didn’t even expect Wikipedia

to have an image for the phrase “pearl-

clutching,” but I love both that it does and

the actual image they used?

Of course, St. Paul did instruct us that, all else being equal, those with healthier consciences should show deference to scrupulous, hypersensitive types: “One believeth that he may eat all things: another, who is weak, eateth herbs … But if thy brother be grieved with thy meat, now walkest thou not charitably” (Romans 14.2, 15). But take note of how he describes the two types. His “strong” are the less anxiety-ridden, the less timid, the less judgmental. I’d argue that Paul is implicitly in favor of strengthening consciences, and—even though this deference rightly extends to permanent vegetarianism, if that’s what it takes to be truly loving— that nevertheless, the weak are both invited to become strong, and are also in the meantime equally under orders not to judge the strong: “Let not him which eateth not judge him that eateth: for God hath received him. Who art thou that judgest another man’s servant? to his own master he standeth or falleth” (Romans 14.3-4).

It’s hard to keep from thinking of the parable of the talents. “I knew thee, that thou art a hard man”; as if that were any way to thank one’s Savior! For that matter, if we were content to define sin or scandal entirely in terms of “whether people are offended by it,” we’ve not only set up a standard of conduct that’s impossible to satisfy and constantly changing, but one that Jesus himself flagrantly refuses to observe, as this exact text exhibits.

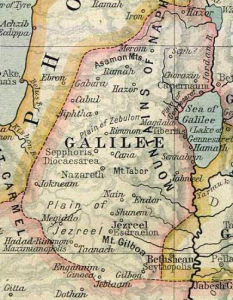

Map of the Galilee ca. 50 CE, by William

Shepherd, first published in 1911.‡

f. went about among/made a circuit of: Here again I made an idiomatic choice, though I’d argue that my idiomatic choice is more literal than the RSV’s. My use of “circuit” here represents the word κύκλῳ [küklō], literally “in a circle” (and yes, this is the same word we get “cycle” from). As we’ve touched on a couple of times, the name of the Galilee (גָּלִיל [galiyl]) literally means “cylinder” or “wheel,” so it’s possible that this is indicating not simply a vague walkabout but a planned “tour” of the whole region.

Footnotes

*Lest I be misunderstood, the doctrine that the Mother of God was perpetually virgin—i.e., not only before but after she bore Jesus—is by no means exclusively Catholic, nor do all Protestants reject it. This doctrine has been the majority view among Christians since the early days of the Church; it remains the official belief of the Assyrian, Catholic, Miaphysite, and Orthodox traditions, and is still a familiar view among Anglicans, Lutherans, and even some branches of Calvinism. (To my knowledge, St. Jerome’s belief that St. Joseph was also perpetually virgin is not common outside of Catholicism, and, while certainly licit, it does not enjoy dogmatic status within the Catholic Church.)

**Declension is the changing of a noun’s endings to suit its function in the sentence, employed in inflected languages (a few other parts of speech may also be declined depending on the language, e.g. pronouns—pronouns in English actually retain more declension than nouns themselves do). Occasionally, however, words occur with an irregular form that appears the same in all cases, and are thus indeclinable. These are often loanwords, foreign names, and the like, though not always.

†The name is normally transcribed “Joses,” as it appears here in the RSV. However, on the principle that the stem of a word rather than its nominative case should really be the English form (a rule observed in names like “Mark” [from Marc-us] and “Mary” [from Mari-a]), we would expect “Joset” or “Joseth.” These names of course don’t exist (though “Joses” isn’t exactly breaking any baby name popularity records itself), so “Joe”—which sort of functions as an independent name, if only in the sense that it can be short for other names as well as “Joseph”—seemed like the best compromise I was likely to find.

‡Notably, Nazareth (near the center) appears as if it’s being depicted as rather larger than usual. I’m not clear whether this is an error on Shepherd’s part, or Nazareth experienced a population surge shortly after the life of Jesus (though I’ve certainly never heard that that was the case), or the larger circles are being used to indicate New Testament towns and the smaller ones are for those from the Old Testament.