The Fifth Sunday after Epiphany

(Or, This Year, the Fifth Sunday in Ordinary Time)

First page of Matthew from the Lindisfarne

Gospels (ca. 715), probably created by

St. Eadfrith, Bishop of Lindisfarne.

I gotta say, it feels good to be getting back to my main translation business here. It so happens I’m doing so right before the beginning of Shrovetide—see my just-ended series on liturgical time for details about that—and our Gospel text is perfect for the occasion. What’s more, this is one of my favorite stories from the Gospels. (It certainly gives the lie to people who claim that the Gospels, or Jesus in particular, aren’t funny: frankly, this miracle is one of the best practical jokes you could ask for.)

It’s also a slightly unusual story. After the first couple chapters, there isn’t a ton of material unique to Luke, but this episode is; I suspect it of being “answered” by the Fourth Evangelist in John 21:1-14, or rather I suspect Jesus of having pulled the same prank twice, because how could you not when an opportunity like this arose (no pun intended)? What’s odder is that, though this story centers on Peter, it isn’t reflected in Mark. This might align with a trend we see in the Gospel of Mark: Namely, stuff that makes Peter seem cool or important, like walking (however briefly) on water or being called the rock on which Jesus will build his Church, is generally omitted altogether or at least downplayed.

CORRECTION: When this post went up, I mistakenly identified yesterday as the first Sunday in Shrovetide (a.k.a. Septuagesima Sunday). It’s not! I goofed.

A Rock on Which Fish Stumble

Before we properly start, a few words about fishing in the Galilee1 back in Ye Olden Days are in order.

Fish.

The kind of fishing being described in this text is not the kind where you sail out to somewhere comfy, secure a rod with a lure, open a book, and wake up suddenly with a sunburn and a salmon dinner—and not just because there aren’t any salmon in the Sea of Galilee. Rods and hooks for one-man fishing existed, but this was a fishing industry, one conducted with gigantic trawling nets designed to capture whole schools of fish at once. The job meant a lot of working at night, mainly because although fish are stupid, they aren’t that stupid: If they see an obstacle, they swim around it like they have every other day of their lives, without needing to know it’s a net first. The solution is to fish at night, when they, like humans, can’t see well (and visibility is far worse underwater). Fishing could be back-breaking work, too; or rather, “finger-breaking” captures it better. Those large trawling nets might be twenty feet high or more, and hundreds of feet long—and making new ones or mending and cleaning old ones would all have been done entirely by hand, remember: no industrial machinery.

Also, while an image search for “Sea of Galilee” will probably turn up tranquil, scenic pictures for the most part, it was actually a rather dangerous place. We can begin with the local topography. Immediately to its north are the mountain ranges of Lebanon and Syria, whose highest peaks exceed nine thousand feet above sea level. The Sea of Galilee, on the other hand, is in a depression that forms the northern end of the unusually deep Jordan Rift Valley, over six hundred feet below sea level.

Now plug the climate into things. In the Mediterranean, air at or below sea level tends to be warm. Conversely, air that has been raised nine thousand feet tends to cool, even at these latitudes; cold air is heavy, so it then sinks, and tends to be looking for somewhere to drop the water vapor it’s carrying, which is even heavier. Accordingly, the slopes that run from the mountains to the Sea of Galilee act kind of like a funnel: Heavy, violent storms can develop there with practically no warning, capsizing or even destroying ships via gigantic waves or, if you were really unlucky, waterspouts. It’s no coincidence Psalm 107 was written well before the miraculous stilling of the storm. In short, comparing a Galilean fishing business to “Deadliest Catch” may be wide of the mark, but it’s not that wide of the mark.

A photo of the Sinai Peninsula and the Holy

Land, taken by satellite Gemini 11 in 1966.

The Wadi Arabah, an extension of the Jordan

Rift Valley,2 is traceable from the Dead Sea.

In our time period, i.e. the late-early/early-mid first century CE, a man from the village of K’far-Nachum named Symeonb bar-Jonah was the, or at least a, manager of a κοινωνία [koinōnia] in this Galilean fishing industry. The word κοινωνία could mean a “company” in the sense fellowship or brotherhood, but also in the sense thing you’re employed by. His coworkers included his brother Andreas, as well as another pair of brothers, Jacob and John, plus their father Zebadiah.

Despite its fickle weather, the Sea of Galilee was well-suited to the fishing business, being thoroughly stocked with edible fish. (Incidentally, “Lake Gennesaret” or “Lake Tiberias” are technically more correct, since this is fresh water, but “Sea of Galilee” is the commoner name.) These include:

- The African sharptooth catfish, a rather creepy species. I mean that literally—it’s able to traverse shallow mud to escape isolated pools. It is also, like a number of edible fish, nocturnal (another reason to fish at night instead of during the day).

- The Kinneret3 bream, or Kinneret bleak, a silver-colored fish only a few inches long. Fish of this type might be used as a garnish, a bit like anchovies today; the “two fish” the little boy in John 6 had with him may have been Kinneret breams.

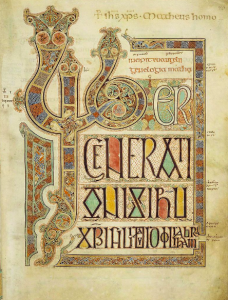

- Multiple varieties of tilapia (which is apparently a tribe, a rank above genus but below family and subfamily … taxonomy is complicated), such as

- the mango tilapia, also called the Galilean tilapia (a useless designation, since these are all tilapia from the Galilee). This is also called “St. Peter’s fish“; it’s a big honker of a thing that easily exceeds a foot in length. I assume it’s called the mango tilapia thanks to the, uh, bluish tint its scales and/or fins sometimes have. Obviously, it is not to be confused with

- the blue tilapia, which looks to be more of a flat silvery-grey, and whose scientific name (Oreochromis aureus) means “golden Oreochromis.“4 Needless to say, these are both different from

- the redbelly tilapia, a bright yellow fish that is also known as “St. Peter’s fish,” and I swear, someone here is punking me, they have to be.

I kid you not, this one is a picture of the

“mango tilapia.” MAKE IT MAKE SENSE.

Luke 5:1-11, RSV-CE

While the people pressed upon him [Jesus] to hear the word of God, he was standing by the lake of Gennesaret. And he saw two boats by the lake; but the fishermena had gone out of them and were washing their nets. Getting into one of the boats, which was Simon’s,b he asked him to put out a little from the land. And he sat down and taught the people from the boat.c And when he had ceased speaking, he said to Simon, “Put out into the deep and let down your nets for a catch.” And Simon answered, “Master,d we toiled all night and took nothing! But at your word I will let down the nets.” And when they had done this, they enclosed a great shoal of fish; and as their nets were breaking, they beckoned to their partners in the other boate to come and help them. And they came and filled both the boats, so that they began to sink. But when Simon Peterf saw it, he fell down at Jesus’ knees, saying, “Depart from me, for I am a sinful man,g O Lord.”h For he was astonished,i and all that were with him, at the catch of fish which they had taken; and so also were James and John, sons of Zebedee, who were partners with Simon. And Jesus said to Simon, “Do not be afraid; henceforth you will be catching men.”j And when they had brought their boats to land, they left everythingk and followed him.

Luke 5:1-11, my translation

It so happened that the crowd pressed up on him [Jesus] to hear the word of God—he was standing beside Lake Gennesaret, and saw two boats standing by the lake, for their trawler-mena had disembarked and were cleaning their nets. He got into one of the boats, which was Symeon’s,b and asked him to go back from the land a little; then, sitting down, he taught the crowds from the boat.c

The Calling of the Apostles Peter and Andrew

(1311), by Duccio di Buoninsegna.

As he finished talking, he said to Symeon: “Go back to the deep water and release the nets for your catch.” And Symeon replied: “Chief,d we wore ourselves out the whole night and took nothing; yet, as you say, I will release the nets.” And when they had done this, they captured a great multitude of fish—it was breaking the nets. So they signaled to their partners in the other boate to come pull them up together; and they came, and both boats were so full, they began to be submerged.

Looking at this, Symeon Rockyf fell onto his knees, telling Jesus, “Go away from me, because I am a man who is sinful,g sir”;h for awe encircled himi and all who were with him due to the catch of fish which they took, and the same went for Jacob and John the sons of Zebadiah, who were in Symeon’s company. And Jesus said to Symeon: “Don’t be afraid; from now on, you are going to be catching live people.”j

So, getting out of the boats onto the land and letting go of everything,k they followed him.

Textual Notes

a. fishermen/trawler-men (ἁλιεῖς): I opted for this word instead of “fishermen” to get away from the mental picture of the guy by himself with a fishing rod. The noun ἁλιεύς [halieus], of which ἁλιεῖς [halieis] is the plural, literally means “salter,” shorthand for someone with business on saltwater.

b. Simon/Symeon: The form Symeon does occur in the New Testament (not only as the name of the quite separate person in Luke 2:25-35, but as St. Peter’s self-appellation in II Peter 1:1), but Simon is far commoner in all contexts. I’ve opted for Symeon instead, on the ground that it may be closer to what St. Peter really called himself (it has a marginally closer correspondence to the Hebrew original שִׁמְעוֹן [Shimṛawn]5; it turns the Hebrew vowel-ish sequence, עו, into a vowel sequence, eo, instead of fusing it like Greek does into a simple o). The name is related to Samuel (meaning “God hath heard”); Shimṛawn/Symeon/Simon instead means “he listens” or “he heeds.”

St. Peter as depicted in The Nuremberg

Chronicle (1493), a late Medieval

encylopedia.

c. to put out … from the boat/to go back … from the boat (ἀπὸ τῆς γῆς ἐπαναγαγεῖν ὀλίγον, καθίσας δὲ ἐκ τοῦ πλοίου ἐδίδασκεν τοὺς ὄχλους): As discussed, the Sea of Galilee is remarkably far below sea level—more than six hundred feet—and in a bowl-like depression. This means that, besides not getting mobbed by his audience, Jesus may have been availing himself of a “natural amphitheater” effect created by the landscape.

d. Master/Chief (Ἐπιστάτα): This is exactly as respectfully-disrespectful as it sounds. That is, the word in itself is not insulting; the total sentence, however, especially as spoken by a responsible person working a difficult job who is probably finally done and would like to go home now, has a distinct “Whatever you say, champ” vibe to it.

e. they beckoned to their partners in the other boat/they signaled to their partners in the other boat (κατένευσαν τοῖς μετόχοις ἐν τῷ ἑτέρῳ πλοίῳ): It seems evident from vv. 9-10 that at least two or three of St. Peter’s other crew were there in the boat with Peter and Jesus at this time; however, the ambiguity of the “they” here leaves open the possibility that Jesus himself was helping haul the catch aboard too.

Jesus Appears on the Shore of Lake Tiberias

(ca. 1890-1900?), by James Tissot.

f. Peter/Rocky (Πέτρος): I am not the first to point out that “Rocky” is a pretty exact equivalent of the Greek Πέτρος [Petros] and the Aramaic כֵּיפָא [Kêyphâ’]. It is interesting to note that, while he’s been in the narrative since the middle of the previous chapter (he has already healed Symeon’s mother-in-law, for instance), it is at this moment—when he falls to his knees before Jesus—that Luke first calls him Πέτρος.

g. a sinful man/a man who is sinful (ἀνὴρ ἁμαρτωλός): This phrase struck me as a bit odd (which is why I went for a translation that would come off slightly clunky). Calling oneself “sinful” is normal enough of course, and even meaning it is not unknown. What caught my eye was ἀνὴρ [anēr]. This is not a “generically masculine” term that would also cover groups of mixed gender in the plural, like ἄνθρωπος [anthrōpos] (“person”) is; it is a “denotatively masculine” term, meaning “man”—or “husband.” Furthermore, the adjective ἁμαρτωλός [hamartōlos], “sinful,” seems to have played a part in the same silly economy of euphemism that, in the twentieth century, caused words like “immorality” to take on a mainly sexual significance.

Christ in the Storm on the Sea of Galilee

(1695), by Ludolf Backhuizen.

Just to be clear, I know of no tradition and am not myself suggesting that St. Peter cheated on his wife before he met Jesus. (And just to stay clear, while I am not eager to make ill-founded accusations against the heroes of my faith, it would make very little difference to that faith if he had, for much the same reasons I’ve always been baffled by people arguing the tradition of the Magdalene being a former prostitute is a “smear campaign.”6) But you don’t have to full-on violate your marriage to have things on your conscience that just make you feel dirty in the presence of the holy. My mind went irresistibly to the lyrics of probably my favorite mewithoutYou song, “Messes of Men”:

They caught me makin’ eyes

at the other boatmen’s wives

and heard me laughing louder

at the jokes made by their daughters. …

With tarnish on my brass,

with mildew on my glass,

I’d never want someone so crass

as to want someone like me.

But a few leagues off from shore,

I bit a flashing lure

and I assure you, it was not what I expected it to be. …

“I do not exist,”

we faithfully insist,

while watching sink the heavy ship

with everything we knew.

Recitation of the Confiteor at a Tridentine-

rite liturgy. Photo by James Bradley,

used under a CC BY 2.0 license (source).

h. O Lord/sir (κύριε): I have, finally, boarded the “there is no single translation of κύριος [kürios] that will always satisfy—sometimes it just has to inconsistently be ‘sir’ and that’s it” train. To my knowledge, this disadvantage is native only to Modern English; even Spanish, a language that has a lot of surprisingly parallel idioms to those of English, can cover the the very different connotations of “lord,” “sir,” and “Mr.” under the efficient term señor. It may even be peculiar to Modern American English. Before the Revolutionary War, we used the title “lord” a lot more freely, making it far more normal as a polite form of address. Now, “lord” is used here almost exclusively as a divine title, and as a result, “O Lord” comes across (as Simon doubtless did not intend, at this time) almost as a confession of Christ’s deity.

Note also how “sir” comes at the end of the sentence. It feels as if Peter has abruptly, wincingly remembered his initial response, complete with Ἐπιστάτα, and specially wants to make it clear that he apologizes for that.

Russian Orthodox ikon of St. Peter (written7

ca. 1500), now housed in the National

Museum of Sweden. Photo by Erlend Bjørtvedt,

used under a CC BY-SA 3.0 license (source).

i. For he was astonished/for awe encircled him (θάμβος γὰρ περιέσχεν αὐτὸν): I love the verb in this verse, περιέχω [periechō]: For one thing, its mere sound is quite lovely; for another, like many Greek verbs, it is a verb with a “prepositional” prefix (it’s adverbial really, but who’s counting8) that I find vivid. The word περί [peri] means “around,” “near,” “about” (in both senses) and “concerning.” The word έχω [echō] is a fairly common verb that normally means “to have,” and therefore got entangled with lots of other ideas, helping-verb style. Alternate translations would have been “surround,” “encompass,” “envelop,” perhaps “fall upon” or “settle on.”

j. you will be catching men/you are going to be catching live people (ἀνθρώπους ἔσῃ ζωγρῶν): This text, funnily enough, has ἀνθρώπους, a form of ἄνθρωπος from note f above. It also has a detail that’s hard to convey concisely in English, but in my opinion alters the atmosphere quite a bit. Jesus’ reply about “catching live men” uses a participle derived from the verb ζωγρέω [zōgreō]. The thing that’s neat about this word is, one of its two components, the older verb ἀγρέω [agreō], is a normal verb of the “hunt/catch/seize” family. Ζωγρέω was made by prefixing the adjective ζωός [zōos], meaning “living, alive.” It thus means something like “to take alive,” “to capture [instead of killing],” or “to catch and release”; and by extension, it came to mean “to revive.”

k. they left everything/letting go of everything (ἀφέντες πάντα): The verb here (technically a participle)—the RSV’s “left,” my “letting go of”—always fascinates me. It comes from ἀφίημι [afiēmi], a compound word that means “to throw out, cast out, or send away,” and it appears all over the Greek New Testament. It’s term we usually see translated as “to forgive”; in other contexts, it can mean: “to abandon or desert”; “to ignore, let pass, excuse, or turn a blind eye to”; “to set free”; “to divorce”; “to send, emit, or dispatch”; “to allow or permit”; and “to give up, turn over, hand over, or surrender.” There aren’t a lot of English words that can convincingly be marshaled as descriptors of multiple dimensions of most of the actions of Jesus, Judas, Peter, and Pilate leading up to the Crucifixion, are there?

Footnotes

1These naming variations have come up before, but (1) it’s been a minute, and (2) you may or may not have read the posts in which they came up. Here’s a run-down, most of which will be relevant in the paragraph that starts “In our time period.”

⋅ the Galilee: Galilee (the original Hebrew name was הַגָּלִיל [ha-Gâlîl] or “the Wheel”; this was likely due to the vaguely circular shape of the northern highlands within the Holy Land)

⋅ Symeon bar-Jonah: Simon son of Jonah (Symeon is the Greek form of the Hebrew original, שִׁמְעוֹן [Shimṛawn])5

⋅ K’far-Nachum: Capernaum (literally “town of Nahum,” i.e. the prophet)

⋅ Andreas: Andrew (a Greek name adopted by some Jews, probably for its meaning, “manly” or “courageous”)

⋅ Jacob: James (we got James out of Hebrew’s original Yaqov via Greek’s Iakobos becoming Latin’s Iacomus)

⋅ Zebediah: Zebedee

2To speak more precisely, both the Wadi Arabah and the Jordan Rift Valley are segments of the same underlying geological feature: the Dead Sea Transform, a tectonic joint where the African and Arabian plates abut each other (Israel, Lebanon, the Syrian coast, and the West Bank are on the African plate, while Jordan and the rest of Syria are on the Arabian plate). The African and Arabian plates are moving in the same direction, but at different rates—unlike e.g. the San Andreas fault, where the Pacific and North American plates move in contrary directions. As a result, earthquakes are infrequent in the Levant—the last one was in the eleventh century!—yet catastrophic in proportion to their rarity. (The Dead Sea Transform is, indirectly, connected to the East African Rift, which may be the beginning of a new oceanic basin, though it sounds like we probably won’t know for sure for at least another five million years.)

3Kinneret and Chinnereth may be variations on the name Gennesaret. “Kinneret” is the oldest of the three names, and may be derived from כִּנֶּרֶת [kinereth], i.e. “harp” or “lyre,” referring to the shape of the lake. Changing a k sound into either a hissing ch sound (as in “Chanukkah,” not “cheese”) or a softened g sound (“give,” not “gentle”) are both forms of lenition, a fairly common sound change cross-linguistically; I don’t know how to account for the inserted –sa– in “Gennesaret” on that theory, though. Alternatively, “Gennesaret” may originate with the name of a plain and town on the lake’s northwestern shores, גִּנּוֹסַר [Ginnawsar]. I was unable to find further details on that name.

4I couldn’t find anything about the meaning of the genus name Oreochromis (but found innumerable helpful explanations that “That means tilapia!”). I assume, but cannot prove, that it does not mean “Oreo-colored.”

5My preferred Hebrew transliteration system, unusually, uses ṛ to transliterate the letter ע, named ayin (or, by this system, ṛayin). It is often transliterated as a ‘—right-facing, to distinguish it from the ‘ used for א, aleph—but it is also often ignored. The sound of ayin had apparently been lost from Hebrew by the time of Christ. Linguists helpfully inform us that it was a “voiced pharyngeal fricative”; we of course all know this phrase as the most popular name for the family dog, but it also means a sound—probably something like the German or French uvular r though even more guttural, back at the epiglottis instead of the uvula. (Alternately, it may have been more like the “blurred” or “buzzing” gh-sound the Modern Greek γ and modern Spanish g represent.) However, even in many fonts that have at least a modicum of serifs—this one, for example—no distinction is made between the two versions of ‘. (Personal, very irked, opinion: This is a bad choice, one that affects multiple languages—Hebrew’s one example, Hawaiian’s another. You designed letters that have serifs, guys; just give us punctuation that has serifs too. This shouldn’t be hard. And frankly, you need to get over Arial anyway. She has a partner; his name is Being Ugly. Get a job, stay away from her.) Ṛ is, first of all, easier to see; it also gives some idea of how the letter may have been pronounced in Classical Hebrew. That said, Modern Hebrew only uses ע for etymological reasons and as a mater lectionis. If reading aloud, it’s best to treat ṛ as a silent letter.

6Admittedly, I have a far lower opinion of adultery than I do of prostitution; but this is beside the point.

7In the Eastern tradition, ikons are properly “written” and not “painted.” In Greek, these verbs are not distinguished, or weren’t in the Koiné period (I’m not familiar with Modern Greek); this is why the verb γράφω [grafō], meaning both “to draw” and “to write,” is related to both graphs and grammar. However, once the distinction appears, as it does in English, Orthodox are quite clear and firm about which verb applies to the ikon. This is because, while any piece of art can be beautiful and can even have a religious subject, in the East, ikons sensu stricto are understood as part of the vehicle of divine revelation. This is why details in an ikon that would likely go unnoticed in the West can provoke strong reactions in the East; features like the placement and gesture of the figures carry theological significance, as part of a visual language.

8Me. It’s me. I am the one who is counting, and will one day compel Anglophone grammarians, by violence if necessary, to Just Be Normal about prepositions (e.g., by admitting that they can also be adverbs).