Series Table of Contents:

Introduction (what sacred/liturgical time is and why we have it)

The Canonical Hours (the Catholic “clock”)

The Former Holy Week (pagan antecedents of the week)

The Seventh Day (the Judaic week and the Sabbath)

The Revelation of the Octave (the Catholic week)

To Everything There Is a Season (Easter computus; fourfold interpretation of Scripture)

The Waxing of the Sun (the literal/meteorological year; the yearly allegory of the life of Christ)

The Waning of the Sun (the spiritual life through the lens of the year)

⇒ A Time to Get, and a Time to Keep (liturgical seasons in the Anglican Use)

The Five Seasons

To every thing there is a season, and a time to every purpose under the heaven:

A time to be born, and a time to die; a time to plant, and a time to pluck up that which is planted;

A time to kill, and a time to heal; a time to break down, and a time to build up;

A time to weep, and a time to laugh; a time to mourn, and a time to dance;

A time to cast away stones, and a time to gather stones together; a time to embrace, and a time to refrain from embracing;

A time to get, and a time to lose; a time to keep, and a time to cast away;

A time to rend, and a time to sew; a time to keep silence, and a time to speak;

A time to love, and a time to hate; a time of war, and a time of peace.

—Ecclesiastes 3:1-8

A portrait of King Edgar (r. 959-975) hailing

Christ enthroned, from the charter of the

abbey of New Minster, located in Winchester

(a quasi-capital under the House of Wessex).

Way back when I started this series—and thought I would have it done in three posts!—I said that, though there are three basic cycles in the Church’s year, it has five basic seasons. About three posts ago, I identified them as i) Advent, ii) Epiphanytide, iii) Lent, iv) Eastertide, and v) Trinitytide.1 Why these five?

Most other seasons are either ancillary to these five or subdivisions of them, and typically in fairly clear ways: e.g., the difference between Lent in the narrowest sense and Passiontide is clearly not crucial. We’ll be turning to these subdivisions in a bit.

The real question is, why Epiphanytide? The presumptive alternative would be to make Christmastide a sixth principal season, or for it to replace Epiphanytide. Isn’t Jesus’ birth obviously more important than the things that happened after it, since he had to be born for them to happen? Further, Christmas is about just one mystery, the Nativity. Epiphany and its season cover several: the visit of the Magi, Christ’s Baptism, and the miracle at Cana (the first miracle of his earthly ministry) are the most prominent. This might make the former festival sound like a better basis for measuring time from, as being more focused, or more stable.

However, odd though this may seem to us, Epiphany is an older solemnity than Christmas. This is more natural than it sounds. Epiphany’s polyvalence encompasses Christmas thematically; the reverse is not the case.

Fresco of the baptism of Jesus (c. 1305)

by Giotto di Bondone, located in the

Scrovegni Chapel in Padua, Italy.

For the overarching theme of the season is suggested by its name: it is about revelation, God’s self-disclosure to mankind—a common thread running through the Nativity, the visit of the Magi, Christ’s baptism, and his first miracle alike. This is probably why the recently-instituted Sunday of the Word of God, which honors sacred Scripture, was placed during this season. The Incarnation, which of course Christmas celebrates, is the supreme instance and heart of revelation (which is partly why, according to one strand of Christian speculative theology, the Incarnation would have taken place even if humanity had never fallen). Obviously, Jesus’ preaching and teaching was both revelatory and preparatory to his self-sacrifice on Calvary. Since Epiphanytide’s themes befit it both to continue the themes of Christmas and to anticipate those of Lent, it forms a natural bridge between the two which Christmastide in itself does not, or not so strongly.

There is also a practical reason Epiphanytide is better suited to be one of the principal seasons than the Christmas season is. Christmastide in the strict sense lasts only until Candlemas, keeping pace with the forty days the Mother of God was ritually unclean.2 This means that, unless Septuagesima Sunday falls on or before 3 February—which it does slightly less than half the time—there is a gap between the end of Christmastide and the beginning of the great Paschal cycle. We’re currently in exactly that gap this year, and won’t be leaving it until the 16th of this month. This gap is covered only by Epiphanytide. (This is a discrepancy between the calendar of the Anglican Use and that of the majority of the Roman Rite. In the latter, though the solemnity is of course preserved, the season of the Epiphany is folded into the broader category of “Ordinary Time,” which I’ve already bemoaned in footnote 5 of this post.)

Part of Horæ Serenæ (1894) by Edward Poynter.

The Horai, or Hours, were Græco-Roman

goddesses typically held to govern either

the seasons or the hours of the day.

So! What do the five seasons look like in detail?

Sumer ond Winter, Lenctentid ond Hærfest*

Feower tida synd getealde on anum geare … Ver is lenctentid … Æstas is sumer … Autumnus is hærfest … Hiems is winter.

Four tides are told in a year … Ver is lengthentide [i.e., spring] … Æstas is summer … Autumnus is harvest [i.e., autumn] … Hiems is winter.3, 4

—Ælfric of Eynsham (c. 955-c.1010), translating St. Bede‘s De Temporum Ratione (“The Reckoning of Time”)5

The specifically Anglican Use structure of the year is presented in The Big Chart, below—and here, at last, the subdivisions of seasons are given, both official and unofficial (the latter are in italics). Here are some guidelines for reading The Big Chart.

- The three overarching, interlocking cycles are underlined, colored (in sky blue, red, and gold), and center-aligned rather than left-aligned.

- Both major seasons and season-defining solemnities6 are shown without indentation; seasonal subdivisions and ancillary seasons, on the other hand, are indented. The more indented it is, the more it depends fr its meaning on the items above and/or below it—usually both.

- Major seasons are in bold and marked with a ✠ (what’s called a cross pattée) the first time they appear. (Subsequent times are ignored, since these only denote unofficial subdivisions of the season.)

- Season-defining solemnities are in capitals.

- Other “cardinal”7 observances (most of which demarcate unofficial subdivisions) are in small capitals; other seasonally-thematic observances are in small standard type.

- As on the calendar page of this blog, observances currently unique to the Anglican Use are in royal blue. (This applies only to actual practices, however. Terminology unique to the Anglican Use abounds, and is unlabeled, because labeling it would be tedious and probably confusing.)

*If you’re wondering why I rearranged the list of seasons from my source here, hum the first four measures of “Great Is Thy Faithfulness” and it’ll make sense.

The Big Chart

The Incarnational Cycle

An illuminated capital depicting the Nativity,

from a 14th-c. missal created in East Anglia,

now housed in the National Library of Wales.

…FEAST OF ST. ANDREW (30 Nov.)

✠ Advent

…The Advent Ember week

…CHRISTMAS (25 Dec.)

……Christmastide: Twelvetide

……Feast of St. John the Beloved Apostle (27 Dec.)

……Solemnity of the Mother of God (1 Jan.)

EPIPHANY (6 Jan.)

…Christmastide: second part

✠ Epiphanytide: first part

…Sunday of the Word of God

…Feast of the Conversion of St. Paul (25 Jan.)

…CANDLEMAS (2 Feb.)

Epiphanytide: second part

…Solemnity of the Chair of Peter (22 Feb.)

Notes: Advent’s ethos is one of vigilant hope; it is classed as a penitential season (which is why its standard color is purple), but its penances are more along the lines of St. Paul’s “I beat my body and make it my slave” than the Lord’s “The Bridegroom will be taken away from them, and then they will fast”—the spare-ness of training, not of mourning. We may note that its first Sunday is in fact always that on or nearest to 30 November, which is the Feast of St. Andrew; this is highly appropriate, since in the Bible, St. Andrew only ever appears (save in lists of the Twelve) leading people to Jesus. In the Ordinariate, the first week of Advent (formerly the third) is designated as an Ember week: provided they don’t land on a feast or solemnity, fasting and abstinence from meat are considered fitting on the Wednesday, Friday, and Saturday of this week, though the only obligatory observance is abstinence from meat that Friday.

The ethos of Epiphanytide, as explained above, is one of revelatory illumination, and its liturgical color is the white of light. Twelvetide (a.k.a. the famous twelve days of Christmas) are its preparatory period; they are well-suited to recalling the patristic tradition, recorded in the letters of St. Ignatius of Antioch, that the virginity of the Mother of God, her conception of the Lord, and his birth, were all supernaturally concealed from the devil—it seems as if he learned of Christ’s birth when Herod the Great did … In any case, this idea of secrecy, or in Scriptural language mystery, thus rightly initiates us into Epiphanytide proper, which also features the Sunday of the Word of God, the Feast of the Conversion of St. Paul, and Candlemas.

The Redemptive Cycle

Relief of the Crucifixion from Canterbury

Cathedral. Photo by Jonathan Cardy; used

under a CC BY-SA 3.0 license (source).

……Shrovetide

…ASH WEDNESDAY

✠ Lent

…The Lenten Ember week

…Passiontide

……Holy Week

………Fig Monday

………Temple Tuesday

………Spy Wednesday

The Triduum

…MAUNDY THURSDAY

…GOOD FRIDAY

…HOLY SATURDAY

✠ Eastertide

…THE OCTAVE OF EASTER

EASTER SUNDAY

…Ascension Thursday

……The Pre-Pentecost Novena

PENTECOST

…Whitsuntide

A 19th-c. Russian ikon of Pentecost.

Notes: This, throughout, is the part of the Church’s year that is moveable; it is also the supreme period of the liturgical year, centering upon Easter, the new Passover that commemorates our escape from bondage to sin and the beginning of our journey to paradise.

The first half is penitential, and this time, mournful; again we turn to purple for our color, echoing the purple robe of the Passion. From Shrovetide, through Lent proper, to Passiontide, and finally into Holy Week itself, the ascesis of the Church’s ritual becomes more pronounced: the Alleluia is laid aside in Shrovetide, the Gloria is silenced in Lent, and the images are veiled in Passiontide. Holy Week is the climax, and the Triduum, the zenith of that climax—conceptually, it is a single liturgy spread over three days, just as the Gospel of John often speaks of the Passion, Resurrection, and Ascension as if they were a single act: “the Exaltation,” as we might say. (Think of the text from John 3, “even so must the Son of Man be lifted up”. Does he mean on the cross? from the tomb? from the face of the earth? All three answers are correct and necessary.)

The second half, however, is all glory. The abridged parts of the liturgy (which momentarily reappeared on Maundy Thursday, but were quickly hushed under Gethsemane’s shroud) return—the whole first week is one continuous Sunday, ritually speaking. The dominant liturgical color is white; however, gold, which can be used in place of any other color, is specially appropriate in this season, and at its close, Pentecost brings a week of red vestments, which at this juncture are less the red of blood than that of fire. Note, too, that Ascension (on the original structure) falls on a Thursday, like Maundy Thursday and Corpus Christi: The words spoken before the Ascension thus align with the two great celebrations of the Blessed Sacrament—”Lo, I am with you always.”

The Trinitarian Cycle

Adoración del Nombre de Dios [“Adoration of

the Name of God”] (1772) by Francisco José

de Goya y Lucientes.

TRINITY SUNDAY

✠ Trinitytide: post-Pentecostal solemnities

…Corpus Christi

…Sacred Heart of Jesus

…Nativity of St. John the Baptist (24 Jun.)

…SOLEMNITY OF SS. PETER AND PAUL (29 Jun.)

Trintytide: second part

…Feast of St. Thomas the Apostle (3 Jul.)

…Feast of St. Mary Magdalene (22 Jul.)

…Feast of St. James the Greater (25 Jul.)

…ASSUMPTION OF THE MOTHER OF GOD (15 Aug.)

Trinitytide: St. Michael’s Lent

…The September Ember week

…Feast of the Triumph of the Cross (14 Sep.)

…MICHAELMAS (29 Sep.)

Trinitytide: Hallowtide

…Feast of St. Luke (18 Oct.)

…ALLHALLOWMAS (1 Nov.)

…ALL SOULS (2 Nov.)

Trinitytide: Doomtide

…CHRIST THE KING

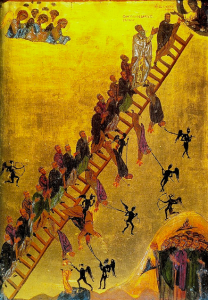

The Ladder of Divine Ascent,

an ikon from the Monastery of St. Catherine

on Mount Sinai.

Notes: The dominant liturgical color of Trinitytide changes from white to green, which in the East is the color used for Pentecost; both there and here, the liturgical significance of green is that it is the color of life, and the life of grace is life in the Trinity.

This long season’s five unofficial divisions may draw our notice. The first embraces the mysteries of the Trinity, the Lord’s Body and Blood (i.e., both the Sacrament and the Incarnation), and the redemptive love of Christ—in other words, the three fundamental roots of all Christian doctrine. This first division then concludes with the birth of St. John the Baptist and the martyrdoms of SS. Peter and Paul, who were the Lord’s herald and the Two Witnesses of the Apocalypse.

The Secrets have been delivered to us, supremely in Epiphanytide and in Pentecost with its three trailing solemnities. As the first part of Trinitytide transitions into the second, we are given our exemplars of what to do with the Secrets. These exemplars continue to emerge: St. Thomas, who journeyed to India; the Magdalene, who was the Apostles’ apostle; St. James bar-Zebedee, the first of the Twelve to be gathered to heaven. This second phase concludes with the gathering to heaven of the greatest of all saints and the most intimate witness of the Incarnation, the Mother of God.

Madonna on a Crescent Moon in Hortus Conclusus

(c. 1450), artist unknown.

Here, as at Candlemas, our orientation shifts. With or without her own death (and there is controversy about that, at least in the West), the dormition of the Mother of God invites the contemplation of death, both in the individual sense and in the sense of eschatology. The third part of Trinitytide is therefore fittingly designated for “St. Michael’s Lent,” a preparation recalling that we made for the Lord’s Pasch, but now looking forward to the feast that honors the bodiless powers who watch over the Church. Our thoughts may turn from there to meditation upon the Church, the Pentecostal body through which the Lord operates on earth. That the Feast of St. Luke, the conciliatory Gentile proselyte who alone recorded Pentecost and who accompanied St. Paul, is likely a coincidence; but (as Chesterton put it) it is a coincidence that really coincides. To progress from here to the Solemnity of All Saints, including those we do not know, is simplicity itself (especially in light of texts like Acts 17:26-28).

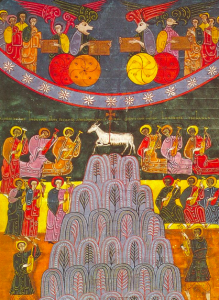

And now we come to the fifth division of Trinitytide and the very last part of the year, when autumn is pressing into winter and thoughts of endings are most upon us. From All Saints we go to All Souls, the only other day of the year when the vestments are black, remembering our dead; the few weeks of November run out, and we conclude with a reminder of the promised Parousia, that is, “presence” or “arrival”—or indeed, “advent.”

The adoration of the Lamb by the elect on

Mount Zion, an illumination from Beatus

of Liébana’s Commentary on

the Apocalypse (c. 776).

And with that, my series on the liturgical year is well and truly done. Ash Wednesday isn’t for another month, so hopefully this means I’ll be able to get the Gospel passage for it translated by then!

(Excessively Long) Footnotes

1In light of this post, since the Sun and Moon govern time in general, we could perhaps align these five seasons with the other five classical planets. Following the same order we use for the days of the week, we get:

Advent = Mars | Epiphanytide = Mercury | Lent = Jupiter | Eastertide = Venus | Trinitytide = Saturn.

The thematic correspondences here fascinate me. Assigning Mars to vigilance, Mercury to enlightenment, Jupiter to kingliness, Venus to new life, and Saturn to eternity are all natural interpretations of the planets according to the Medieval model of astronomy, and all extremely well-suited to the liturgical seasons they are pinned to. At least, this is so if our idea of “kingliness” is the kind expressed in The Horse and His Boy, an idea which few Medieval monarchs practiced but nearly all Medieval people would warmly have approved of, or pretended they did: “For this is what it means to be a king: to be first in every desperate attack and last in every desperate retreat, and when there’s hunger in the land … to wear finer clothes and laugh louder over a scantier meal than any man in your land.”

2This sometimes gives people the impression that the Torah was negative about childbirth out of misogyny, or something of that sort; I believe this is a huge misunderstanding. Ritual impurity could be a punishment in the Mosaic Covenant. However, many laws about ritual purity are obviously pragmatic: e.g., human and animal corpses were unclean, meaning you (normally) weren’t supposed to touch them—broadly good advice. Additionally, being unclean meant release from, even restriction from, certain religious duties. In an age before modern medicine, something as messy and sometimes dangerous as childbirth does seem to invite the label “unclean” in an everyday sense, with or without religious strictures; and I dare say a mother who has just given birth could use a break from the full rigor of observing the Torah! I’m therefore inclined to interpret the forty days’ impurity (or, for those who gave birth to girls, eighty days) as a kindness, not an insult.

3I translated this so as to accent linguistic continuity. A rendering that instead went with the natural way a modern English speaker would convey this information would probably say enumerate, time, and spring, not “tell,” “tide,” and “lengthentide.” The word “tell” has mostly lost the idea of counting, a meaning it still conveyed when we coined the phrase “to tell time.” Speaking of which, that phrase might once have taken the form “to tell tide,” but the meaning of “tide” is now much restricted and somewhat altered to the specifically marine phenomenon. For the seasonal names, see the next footnote.

4About these four seasonal names:

i) The thing that gets longer during “lengthentide,” or spring, is the sunlit half of the day. The term lencten (shorn of the –tid suffix) is still used in English for religious purposes, but its pronunciation and spelling have been simplified to “Lent.”

ii) Sumer (or sumor) appears to go all the way back to a Proto-Indo-European word: *semh2-, meaning “summer” or “year.” (The asterisk at the beginning of that word indicates that it’s a reconstruction, not something recorded in writing, while h2 represents one of the three laryngeal sounds PIE is usually reconstructed as having. H2 may have been a sound like the ch in “Bach,” but made further back in the throat, like the Arabic q or French r. However, there are issues with laryngeal theory; not all linguists agree that PIE had them, or how exactly they sounded.)

iii) Hærfest is still nearly-straightforward English. However, because that f falls in the middle of a word, we shifted its pronunciation and eventually its spelling to v—which is also how we wound up with things like knives, clothes, and staves as the (original) plurals of knife, cloth, and staff.

iv) Finally, the ancestry of winter is not entirely certain, but it is thought to descend from Proto-Germanic *wintruz. This may ultimately come from PIE *wódr̥ “water.”

5Ælfric of Eynsham was a Benedictine abbot and preacher, part of the second generation of the English Benedictine Reform. This was a late tenth-century movement in the English Church, led by St. Dunstan (among others), who was Archbishop of Canterbury from 960 to 988. (This is why some Anglican and English Catholic liturgical books are named “St. Dunstan’s” such-and-such.) My source for the Old English is this selection from an article published online by Cambridge University Press.

6If you are wondering what the difference is between a “solemnity” and a “feast,” and so forth, here’s the short version. There are four basic ranks days can have in the Roman calendar:

I. Solemnities, which override everything except Easter and a few related paschal observances (“the paschal pals,” as we don’t call them); if these can’t be celebrated on their normal dates, they’re often moved to the next available date rather than skipped.

II. Feasts, which tend to override everything but solemnities and some Sundays (these are more prone to be just skipped instead of moved when they conflict with something else).

III. Saints’ memorials, which override ferias (but pretty much always skipped if they clash with anything else).

IV. Ferias (ordinary weekdays).

The real system is more complex than this. For example, there are a handful of “greater ferias,” which aren’t celebratory and are thus not solemn in the proper sense (solemnities are occasions of joy), but are ranked with solemnities for other reasons—Ash Wednesday is an example. However, this stuff is determined in advance, by officials in the hierarchy; you only really need to understand how it all interlocks if you’re designing an Ordo calendar for an upcoming year, or something like that. And if you are doing that, well, I’m flattered and confused that a member of the hierarchy is reading my blog!

7To be clear, “cardinal” observance is not an official designation in the Church’s ritual. I have borrowed it from a former pastor at my parish, who used cardinal in its etymological sense, from the Latin cardo “hinge”; feasts (or greater ferias) that are cardinal in this sense mark transitions from one thematic period of the year to the next. Candlemas is an excellent example: It concludes Christmastide, but the prophecy of St. Simeon, centering as it does on the Passion and the anguish of the Mother of God, turns our gaze from the Nativity toward the Crucifixion.