Series Table of Contents:

Introduction (what sacred/liturgical time is and why we have it)

The Canonical Hours (the Catholic “clock”)

⇒ The Former Holy Week (pagan antecedents of the week)

The Seventh Day (the Judaic week and the Sabbath)

The Revelation of the Octave (the Catholic week)

To Everything There Is a Season (Easter computus; fourfold interpretation of Scripture)

The Waxing of the Sun (the literal/meteorological year; the yearly allegory of the life of Christ)

The Waning of the Sun (the spiritual life through the lens of the year)

A Time to Get, and a Time to Keep (liturgical seasons in the Anglican Use)

“Or a Table to Play Scrabble On,”

So! We have discussed the liturgical hours and what they’re for. The next step up in time is from hours of the day to days of the week. I’m going to start by laying out some background that’s primarily mythological, before moving on to a more properly theological analysis in my next. That background will take us to some weird places—though fitting, in a way, since we’re about to celebrate a holiday famously made known by a star—so strap in.

Alchemical symbols of the planets,

presented in Basil Valentine’s

The Last Will and Testament of 1670.

Most cultures have had sort of a week from time immemorial—a cycle of around five to ten days that, in some way, defined patterns of work. A handy example is the Roman nundinæ or “ninedays,” so named, of course, because they were eight days long; they dictated market days in the environs of the city. Our own seven-day week originates in Judaic ritual, laid down in the Torah. This may in turn have been derived from a seven-day week observed by the ancient Babylonians,1 probably for astrological reasons.

Without telescopes, the human eye can detect seven celestial bodies that visibly move relative to the backdrop of “fixed” stars. (The “fixed” stars actually do move, which is why Polaris has not always been and will not always be the north star,2 but they only visibly move relative to one another on a scale of many centuries.) These seven bodies are therefore known as the seven classical planets—”classical” because they are from classical antiquity, and “planets” from the Greek πλανήτης [planētēs], “wanderer.” These seven exceptional celestial bodies are probably the origin of the idea that seven is a sacred number, held by the Babylonians and Akkadians as well as the Israelites. The Babylonians associated the classical planets with seven of their gods: Shamash, a just and omniscient solar deity; Sin, a benignant lunar and pastoral god; Nergal, a sinister god of death and disease; Nebo, a god of literacy and commerce; Merodach or Marduk, the patron deity of Babylon (who also gave us one of the funniest names in the Bible, that of the king Evil-Merodach); Ishtar, a fertility goddess who also ruled war; and Ninip, an agricultural deity.

The seal of Ḥašḥamer (c. 2100 BCE). The seated

figure is likely King Ur-Nammu of Ur; the bene-

volent Sin (symbolized by the crescent) watches

the protectress Lamma bring Ḥašḥamer to him.

The Greeks interpreted these as equivalents of gods from their own pantheon. These weren’t as uniform as they’re sometimes implied to be—on the island of Samos, for instance, Hera (rather than Poseidon) was the goddess of ships. But they generally opted for a consistent set of seven: Ἥλιος [Hēlios], Σελήνη [Selēnē], Ἄρης [Arēs], Ἑρμῆς [Hermēs], Ζεύς [Zeus], Ἀφροδίτη [Afroditē], and Κρόνος [Kronos]. The Romans in turn identified these deities with their own Sōl, Lūna,3 Mars, Mercurius, Iupiter (who was also called Iovis), Venus, and Saturnus. Their equivalences in modern astronomy are probably clear enough.

The Romance names for the days of the week still largely reflect these deities. Sunday and Saturday tend to throw the pattern off, as their names normally come from words or phrases meaning “the Lord’s day” and “sabbath”; but for the other five, look at the Spanish lunes, martes, miércoles, jueves, and viernes—or think, as one does, of the Friulian language with its lunis, martars, miercus, joibe, and vinars.

Asgard Called, Didn’t Say What It Was About

Returning to the classical planets—the Sun, the Moon, Mars, Mercury, Jupiter, Venus, and Saturn. Kind of an odd order to name them in, isn’t it? Well, yes. However, it’s less odd than it looks, for two reasons.

i. You’ve been listing the classical planets like this pretty much your whole life. The reason you haven’t realized it before is that you’re used to doing it in Anglo-Saxon, and also to sticking “day” on the end of each planet’s name:

Anglo-Saxon — Modern English

ᛋᚢᚾᚾᛖ [Sunne] — Sun-

ᛗᚩᚾᚪ [Mōna] — Mon-

ᛏᛇᚹ [Tīw] — Tues-

ᚹᚩᛞᛖᚾ [Wōden] — Wednes-

ᚦᚢᚾᚩᚱ [Þunor4] —Thurs-

ᚠᚱᛇᚷ [Frīg] — Fri-

ᛋᚫᛏᛖᚱᚾ [Sætern] — Satur-5

Hang on, though—the Sun, the Moon, and Saturn, fine; but in what way is “Tiw” the name of “Mars”? By the same process the Romans used to equate the Greek pantheon with their own, a process known accordingly as interpretatio græca. The reasons behind it aren’t always clear, but the Romans did have a standard who’s-who of which deities in Germania lined up with which Roman ones, and the Saxons and Angles were Germanic peoples. The Romans’ Sol was their Sunne, Luna was Mona, Mars was Tiw, Mercury was Woden, Jupiter was Thunor, and Venus was Frig; Saturn seems to have had no Germanic equivalent (perhaps because he was an agricultural deity, and the various nations of Germania were more inclined to hunting than to tilling, according to the Romans at least). Because so little of Anglo-Saxon paganism was preserved after the conversion of England to Christianity, these deities are now more familiar to us under their Scandinavian names: Tyr, Odin, Thor, and Frigg.

Ptolemy Ptoday

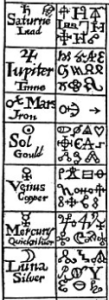

ii. The other reason is the now-obsolete astronomical model used in the ancient world: the geocentric system, also called “Ptolemaic” after Claudius Ptolemy, a second-century geocentrist astronomer who produced the Almagest, one of the most rigorously accurate pre-Galilean books ever written on astronomy. (I.e., it was accurate in terms of predicting what you would see in the sky; admittedly, he was mistaken about why you would see it. After all, he was relying on the best science available to him, like a chump, instead of intuiting what you and I would be taught in school many hundreds of years later.) Take a look at the woodcut below, which is divided into twelve unequal rectangular panels:

The bottom two panels depict the earth itself6—which, to correct a common error, was viewed by the ancients and medievals not so much as the center, but as the bottom of the universe, indicating its unimportance. The upper three panels lie at and beyond the edge of the material cosmos, and need not detain us. The seven panels in the middle house the classical planets: From the lowest up, we have the Moon, Mercury, Venus, the Sun, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn.

Now, imagine you’re an ancient Babylonian, designing a seven-day week to honor each of the classical planets in turn. The Sun and Moon are the two brightest, biggest things in the sky, so it kind of makes sense to put those two first. If you do that, though, how do you want to arrange the other five planets? Because if you just list the rest in ascending or descending order, there isn’t a consistent pattern in your week. You are a Babylonian (i.e. an incredible math dork); you’ll be bothered by knowing that. You could list them in descending order of brightness, maybe? Which puts Jupiter next—no, sorry, Venus. No, it is Jupiter … wait, can you even tell, when Venus is always so close to sunset and sunrise? Again, you’re bothered by this (vid. sup., “dork”). But then you hit on an idea.

There are—as you, a geocentrist, suppose—two planets between the Moon and Sun, and three between the Sun and the edge of the cosmos. You’ve started in the middle, and then jumped down to the bottom: what if you kept doing that? You’d get sort of a braided list:

The Sun…….Mars……Jupiter……Saturn

The Moon…Mercury……Venus

Sunday…..Tuesday….Thursday…Saturday

Monday….Wednesday….Friday

Okay, that is kinda cool. But also, like … just why?

Emulation of the Absolute

The solar system (do not machine wash)

Joseph Campbell authored The Hero With a Thousand Faces, the book by which the idea of the monomyth or “hero’s journey” was introduced to literature and cinema. Now, Campbell was a twentieth-century academic with an interest in anthropology: in other words, a great deal of what he wrote was overconfident drivel. But there’s also a pretty good fraction of it that wasn’t, or that remains a credible interpretation of real evidence. There is a passage in his Primitive Mythology that suggests the feeling which probably animated the astral cult that originally gave rise to the week:

The whole city, not simply the temple area, was now conceived as an imitation on earth of the cosmic order, a sociological “middle cosmos,” or mesocosm, established by priestcraft between the macrocosm of the universe and the microcosm of the individual … The king was the center, as a human representative of the power made celestially manifest either in the sun or in the moon …; the walled city was organized architecturally in the design of a quartered circle …, centered around the pivotal sanctum of the palace or ziggurat (as the ceramic designs around the cross, rosette, or swastika); and there was a mathematically structured calendar …

Three hundred and sixty degrees, then as now, represented the circumference of a circle—the cycle of the horizon—while three hundred and sixty days, plus five, marked the measurement of the circle of the year, the cycle of time. The five intercalated days that bring the total to three hundred and sixty-five were taken to represent a sacred opening through which spiritual energy flowed into the round of the temporal universe from the pleroma of eternity … Comparably, the ziggurat, the pivotal point in the center of the sacred circle of space, where the earthly and heavenly powers joined, was also characterized by the number five; for the four sides of the tower … came together at the summit, the fifth point, and it was there that the energy of heaven met the earth.

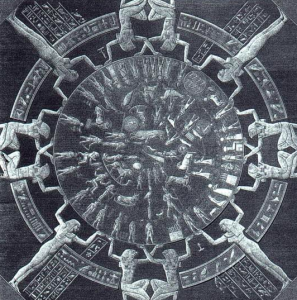

A 19th-c. engraving of the Dendera Zodiac,

a ceiling decoration from the well-preserved

temple of Hathor in Dendera, near the center

of Egypt (by its modern borders).

… And if we now try to convey in a sentence the sense and meaning of all the myths and rituals that have sprung from this conception of a universal order, we may say … “Thy will be done on earth, as it is in heaven.” … Life on earth is to mirror, as nearly perfectly as is possible in human bodies, the almost hidden—yet now discovered—order of the pageant of the spheres.

Or, to give it the form it takes in Dante:

Like to a wheel whose circling nothing jars,

My will and my desire were revolved

By the love that moves the sun and the other stars.

—Paradiso XXXIII.143-145

The Secret of the Menorah

Now, whether all this is, historically, where the Jews got the seven-day week is hard to know for certain. Still, it’s intriguing that the sabbath corresponds to Saturday, the day named in honor of the most slow-moving of the classical planets—especially since the Hebrew names for the days of the week are just ordinal numbers: yom rishon or “first day” for Sunday, yom sheni or “second day” for Monday, etc., so that the weekday names probably wouldn’t have prompted the Jews to independently come up with a link between the seventh day and rest.

Moreover, the Hebrew Bible emphasizes that the sun, moon, and stars are at most mere angelic attendants to the Lord of Hosts, “for all the gods of the nations are idols, but the LORD made the heavens.” I’m therefore struck that, in the Tabernacle and Temple, the Holy Place (still one step removed from the Holy of Holies) was lit by the מְנוֹרָה [m’nôrâh],7 a word which typically just means “light” or “lamp,” but is very carefully described to have been seven-branched. As if to say of this “pageant of the spheres,” already known to be the dreadful and majestic archetype of the nature of man, Even this is no more than the lamp which stands outside of My innermost mystery.

A reconstruction of the Menorah, created in

2007 by the Temple Institute of the modern

state of Israel.

Footnotes

1Israelite and Babylonian civilization were in contact and capable of mutual influence for many centuries before the Exile. Because of the placement of the Syrian and Arabian Deserts, Canaan is naturally open to overland exchange with the Nile Delta from the south and with both eastern Anatolia and northwestern Mesopotamia from the north. Though it had previously been the center of Hittite civilization, in the early Iron Age (roughly ca. 1200 to ca. 600 BCE, during which most of the events recounted in the Hebrew Bible took place), no single regional power usually controlled Anatolia; Egypt, Assyria, Babylon (briefly), and eventually Persia were the dominant nations in the Near East, with a short period of Israelite-Judahite flourishing some time around 1000-900 BCE, associated with the reigns of David and Solomon.

2This has to do with the precession of the equinoxes, which we don’t need to get into in detail, but amounts to the earth’s axis sort of wobbling about and therefore pointing (or nearly pointing) to different stars over the millennia. For instance, from the fourth to the second millennium BCE, a star in the constellation Draco, named Thuban or α Draconis, was the north star; around the year 3000, Errai (or γ Cephei) in the constellation Cepheus will become the north star for a couple thousand years.

3Whether Lūna was an independent goddess to the Romans is not clear. Juno and Diana were both lunar deities, and given the peculiar importance of Juno (she and Jupiter and Minerva formed the “Capitoline triad,” anciently the three most august gods of Rome), it is possible that Lūna was more along the lines of an alternate name or epithet for Juno.

4The letter Þ (þ in lowercase) is named thorn, and was invented as part of the runic alphabets used throughout northern Europe in Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages. It fell out of use among English-speakers during the Renaissance, when the printing press became popular: the device was invented in regions where German was spoken, which had long since lost the th sound þ represents, and Latin (the international language) didn’t have the letter or sound either. The th sound is relatively rare cross-linguistically in general, in fact, so not many people wanted to add a key to the printing press that’d hardly get used. Accordingly, the standard form of the printing press was one without a þ, and English speakers learned to use the digraph “th” in its place.

5I can confirm or deny that I listed these in this way merely because I think Anglo-Saxon runes look cool, but I choose not to. (I cannot, however, explain why the display settings of either WordPress or Patheos go wonky when presented with ᚫ—a rune whose name is spelled æsc and pronounced “ash,” and which made the a sound of “cat”—so that it will display it but won’t line it up properly with the other runes.)

6The wobbly zig-zag shapes in the second panel from the bottom are flames. You’ll remember that the earth, in classical physics, was made up of four elements: earth, water, air, and fire. Flames and heat rise, as people already observed at the time. Hence, fire was considered the lightest of these elements, and a sphere of pure (and therefore invisible) elemental fire was assumed to exist somewhere between the earth and the moon, or perhaps right at the moon. Beyond the moon lay “the heavens” proper, which—because (as was thought at the time) they did not change, as things in the terrestrial domain do—were assumed to be made of a different element, not present on earth. This fifth element was called æther, from the Greek αἰθήρ [aithēr], “sky, heaven” or “pure air.” This, incidentally, is why the adjective “ethereal” means what it does.

7Strictly speaking, the term Menorah is properly applied only to this lost piece of the Temple’s furniture, or of course to depictions of it. What are often casually called “Chanukkah menorahs” are more appropriately referred to as chanukkiahs (or chanukkioth, to give it its Hebrew-form plural); these are distinguished by their nine, rather than seven, branches—eight for the eight candles of the holiday, and one for the “attendant” candle, offset in height from the rest, that is used to light them.