Series Table of Contents:

Introduction (what sacred/liturgical time is and why we have it)

The Canonical Hours (the Catholic “clock”)

The Former Holy Week (pagan antecedents of the week)

⇒ The Seventh Day (the Judaic week and the Sabbath)

The Revelation of the Octave (the Catholic week)

To Everything There Is a Season (Easter computus; fourfold interpretation of Scripture)

The Waxing of the Sun (the literal/meteorological year; the yearly allegory of the life of Christ)

The Waning of the Sun (the spiritual life through the lens of the year)

A Time to Get, and a Time to Keep (liturgical seasons in the Anglican Use)

The Primordial Week

So! To review: We have introduced sacred time as a concept; we’ve discussed the canonical hours; and we’ve done some background on the seven-day week.

You may have noticed, it was mostly non-Biblical background. One of the small ironies here is how little the background will directly impinge on the foreground. The myth of the Dying and Rising God seems to have been enacted in real life among the one Mediterranean nation, the Jews, who were not familiar with the myth. Likewise, the maxim Thy will be done on earth as it is in heaven seems to have been explicitly enunciated among that one nation, who—though keeping the seven-day rhythm it involved was among their gravest religious duties—had only the vaguest idea of the astral symbolism the week is pregnant with, and whose mathematical and astronomical knowledge seems to have been oddly poor,1 despite being surrounded by peoples who were advanced in exactly those areas of study.

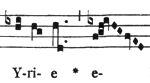

An orrery, a model of the solar system—this

models the inner solar system only, with

Mars offscreen. Photo by Kaptain Kobold,

used under a CC BY-SA 2.0 license (source).

Anyway. We get an account of the seven days of the week right at the beginning of the Bible. The Sabbath has, of course, been locked decisively to Saturday, the day of the slowest-moving of the classical planets; this may hint that there was, at some point in Israelite history, a conscious link between the days of the week and the classical planets. Let’s review the modern week through the creation pattern we find in Genesis 1.

Sunday | the Sun | Gen. 1:3-5

And God said, “Let there be light”: and there was light. And God saw the light, that it was good: and God divided the light from the darkness. And God called the light “Day,” and the darkness he called “Night.” And the evening and the morning were the first day.

Monday | the Moon | Gen. 1:6-8

And God said, “Let there be a firmament in the midst of the waters, and let it divide the waters from the waters.” And God made the firmament, and divided the waters which were under the firmament from the waters which were above the firmament: and it was so. And God called the firmament “Heaven.” And the evening and the morning were the second day.

Tuesday | Mars | Gen. 1:9-13

And God said, “Let the waters under the heaven be gathered together unto one place, and let the dry land appear”: and it was so. And God called the dry land “Earth”; and the gathering together of the waters called he “Seas”: and God saw that it was good.

And God said, “Let the earth bring forth grass, the herb yielding seed, and the fruit tree yielding fruit after his kind, whose seed is in itself, upon the earth”: and it was so. And the earth brought forth grass, and herb yielding seed after his kind, and the tree yielding fruit, whose seed was in itself, after his kind: and God saw that it was good. And the evening and the morning were the third day.

An image of the six days of creation derived

from a work by St. Hildegard of Bingen

(12th c.); it seems to accord with Augustine’s

view that “light” means angels.2

Wednesday | Mercury | Gen. 1:14-19

And God said, “Let there be lights in the firmament of the heaven to divide the day from the night; and let them be for signs, and for seasons, and for days, and years: and let them be for lights in the firmament of the heaven to give light upon the earth”: and it was so. And God made two great lights; the greater light to rule the day, and the lesser light to rule the night: he made the stars also. And God set them in the firmament of the heaven to give light upon the earth, and to rule over the day and over the night, and to divide the light from the darkness: and God saw that it was good. And the evening and the morning were the fourth day.

Thursday | Jupiter | Gen. 1:20-23

And God said, “Let the waters bring forth abundantly the moving creature that hath life, and fowl that may fly above the earth in the open firmament of heaven.” And God created great whales, and every living creature that moveth, which the waters brought forth abundantly, after their kind, and every winged fowl after his kind: and God saw that it was good. And God blessed them, saying, “Be fruitful, and multiply, and fill the waters in the seas, and let fowl multiply in the earth.” And the evening and the morning were the fifth day.

Friday | Venus | Gen. 1:24-28, 31

And God said, “Let the earth bring forth the living creature after his kind, cattle, and creeping thing, and beast of the earth after his kind”: and it was so. And God made the beast of the earth after his kind, and cattle after their kind, and every creeping thing that creepeth upon the earth after his kind: and God saw that it was good.

And God said, “Let us make man in our image, after our likeness: and let them have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over the cattle, and over all the earth, and over every creeping thing that creepeth upon the earth.” So God created man in his own image, in the image of God created he him; male and female created he them. And God blessed them, and God said unto them, “Be fruitful, and multiply, and replenish the earth, and subdue it: and have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over every living thing that moveth upon the earth.” … And God saw everything that he had made, and behold, it was very good. And the evening and the morning were the sixth day.

Obviously Friday is the greatest of these six. There are also a handful of intriguing correspondences here—the association of Sunday with light as such, of Monday with water (remember that the Moon governs the tides), or of Mercury, a planet often linked with intellectual deities, with the mathematically intricate work of calculating the calendar.

A few other elements stand out on closer analysis. To start, there is the elaborate structure exhibited in the two sets of three days: on the first three, “realms” are created (day and night, skies and seas, dry lands and vegetation), and on the fourth through sixth, these realms are “peopled” (stellar bodies, birds and fish, animals and mankind). Or again, within each set of three days, we have a threefold pattern of increasing divergence: days one and four feature singular acts of creation; days two and five each feature a more two-sided one; and days three and six both feature two distinct creative acts on a single day.

An 18th-c. diagram of the apparent motion of

the Sun, Mercury, and Venus as seen from

the Earth. By James Ferguson, based on a

design by Giovanni Cassini.

There are also a few puzzling elements here, which I’m not sure what to do with. For example, when God starts, he names the things he makes, but he suddenly desists as of Wednesday—the interruption is conspicuous, as it forces the writer to circumlocute about “the greater and lesser lights” rather than use the names of the sun and moon. Perhaps (like several orations in the prophets) this is a subtle jab at idolatry, meant to make the point that the stars are not only God’s servants, but man’s too, and therefore man’s to name, like the animals. Or note that, alone in the cycle, Monday does not feature the signal phrase “God saw that it was good” before the day concludes.

In any case, all of this builds over Genesis 1, from the earth being “without form and void” to the opening verses of the next chapter and the narrative’s great culmination:

The Sabbath

Saturday | Saturn | Gen. 2:1-3

Thus the heavens and the earth were finished, and all the host of them. And on the seventh day God ended his work which he had made; and he rested on the seventh day from all his work which he had made. And God blessed the seventh day, and sanctified it: because that in it he had rested from all his work which God created and made.

This departs dramatically from every day we’ve read thus far. Nothing is created, nor named, nor even pronounced “good” (though the day is blessed). And what else is missing?

Time itself. No evening falls; no morning dawns. The Sabbath opens onto eternity.

An illustration of God resting on the seventh

day, from a late 17th-c. Russian Bible.

The observance of the Sabbath is treated with literally deadly seriousness in the Hebrew Bible. Immediately after designating his chosen artisans for the Tabernacle, God then tells Moses:

Verily my sabbaths ye shall keep: for it is a sign between me and you throughout your generations; that ye may know that I am the LORD that doth sanctify you. Ye shall keep the sabbath therefore; for it is holy unto you: every one that defileth it shall surely be put to death: for whosoever doeth any work therein, that soul shall be cut off from among his people. Six days may work be done; but in the seventh is the sabbath of rest, holy to the LORD: whosoever doeth any work in the sabbath day, he shall surely be put to death.

—Exodus 31:13-15

Even circumcision—which is also the sign of a covenant—is not imposed with such gravity. Genesis 17 tells us that “the uncircumcised man child whose flesh of his foreskin is not circumcised, that soul shall be cut off from his people.” That “cutting off,” or כָּרֵת [kâreth], does not mean execution; at least, probably not: interpretations vary. It does seem to mean permanent, complete ostracism, including but not limited to exile. It likely even entails rejection from burial in a Jewish graveyard, if the analogy between “cut off from his people” and the stock death euphemism “gathered to his fathers” is deliberate.

But to violate the Sabbath—this was death. It’s a penalty we see carried out in Numbers 15, before the entirety of the Torah has even been revealed.

The Creation (ca. 1900), by James Tissot.

We may, naturally enough, feel uncomfortable with that kind of severity over something as harmless as picking up some sticks. At any rate, I sure do. Partly because of that discomfort, I’m not entirely sure where to put Numbers 15 on the historicity scale: the scale has one end labeled “fictional object lesson, included to make a theological point,” while the other says “straightforward, factually correct description of a thing that happened, included because it happened.”3 But wherever on that scale that text from Numbers does properly belong, it does definitely make this point: The Sabbath is to be taken seriously. And when you stop to think, it does kind of track we’d have to be commanded to do this. We will be coming back to this idea, with a vengeance, so file it away in your mind while we proceed.

(Do Not) Work It

In order to keep this commandment, however, the Israelites needed an idea of what counted as “work.” Gathering firewood evidently did. What about using firewood you gathered yesterday to cook dinner? Or was cooking dinner even allowed? And if not—I mean … is eating “work”? Is fasting? When the Pharisees got on the disciples’ cases for plucking ears of wheat on the Sabbath because that’s “the work of a reaper” (the story can be found in Matthew 12, Mark 2, and Luke 6), was there a level on which they were just right?

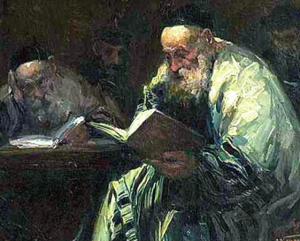

Talmudysci [Talmudists] (ca. 1930-1940?),

by Adolf Behrman.

The only thing we’re told about God before being told that we are made in his image, is that he is a God who makes things. Based on the idea of work as creation, then, rabbinic tradition identifies no fewer than thirty-nine מְלָאכוֹת [m’lâ’khôth], or categories of work prohibited on the Sabbath. These were part of the Oral Torah, the interpretation and application that (in the mainstream Judaic view) was given to Moses alongside the Written Torah, completing it—understanding and explaining what is meant by “work” is kind of a perfect example of why such a thing would be necessary, since language, economies, and technologies change all the time. We don’t have to get into the weeds, but let’s look the m’lakhoth over at least.

-

- carding (i.e., combing wool or similar fibers)

- constructing

- cooking

- curing (or “salting“)

- cutting (i.e., for construction—this isn’t about cutting a bite of food or anything)

- demolishing

- dyeing

- erasing

- extinguishing (no, this doesn’t mean Jewish firefighters can’t put out fires on Saturdays: anything that saves a life is not only permitted but required on the Sabbath)

- flaying

- gathering (e.g., picking a batch of grapes)

- grinding (duh)

- igniting

- joining (or “sewing,” but this covers things like using adhesives)

- killing (i.e., animals; the Fifth Commandment4 also applies Sunday to Friday)

- kneading (more exactly something like “mixing,” as dough is not its only application)

- laundering

- looping (more exactly “making two loops”—has to do with loom-weaving)

- perfecting (or “completing”; see footnote 5)

- planting

- plowing

- reaping

- scoring (i.e., scoring an object before cutting it)

- shearing

- sifting

- smoothing (or “sanding”)

- sorting

- spinning (i.e., thread; do the office chair thing to your heart’s content)

- tearing

- threshing

- transporting

- trapping

- tying

- unraveling

- untying

- warping (no, not the Star Trek kind6—also has to do with loom-weaving)

- weaving (with or without a loom)

- winnowing

- and of course, writing

The point here is how extensive, and thus how psychologically and practically potent, the symbolism of Sabbath ritual was and is. It’s not just “a break”; the Sabbath interrupts your life.

A Digression on the Oral Torah

But by now, and perhaps especially with the mention of the Oral Torah, many Christian readers will have begun mumbling “hedge about the Law,” alluding to the trope in Christian circles—especially evangelical ones—that the Jews of Jesus’ day were too legalistic, and rejected him in favor of man-made traditions. The very phrase “hedge about the Law” is taken from Judaic descriptions of halakhah, i.e. interpretation and application of the Torah, but it is used in these circles almost as a shorthand for being legalistic.

Now, in mere fairness, I have to admit I uncritically accepted this way of speaking and thinking for many years; my hands aren’t lily-white here. But I must also point out that these tropes are unjust, very ignorant, and a breeding ground for anti-Semitic sentiment.7 I do believe there is good reason to think Jesus was reacting against the rigorism of Beyt Shammai, an increasingly popular school among the Pharisees in the first century. His own theology and halakhah seem to align on the whole with the older, more generous outlook of Beyt Hillel (with a very few exceptions). But what he absolutely isn’t doing is throwing out the concept of the Oral Torah, which is the “hedge about the Law”8; its purpose was precisely to guide people away from mere “letter of the law” applications! The “extensions” of the commandments that Jesus sets forth in the Sermon on the Mount are examples of just the kind of thing the Oral Torah exists to do—closing off loopholes, restoring the practical purpose of the command, refixing and refocusing our attention. If anything, Jesus’ castigations of formalism and artificial traditions are recalling the Oral Torah to its purpose, not invalidating it.

A dull, annoying, technical conversation about the Written and Oral Torah is in order here; however, I would prefer not to. (Also, I’ve written about the subject once or twice before.) For our purposes, I’ll simply point out two things:

- Any question can be asked in bad faith; and

- In itself, “What does ‘work’ in the command Do no work mean?” is an obviously reasonable thing to ask.

So, yes, the list of m’lakhoth may be a little dizzying—even short passages from the Mishnah are often like that to the unprepared (I speak as one of the unprepared). But it isn’t in any way impious or unreasonable.

The Lord’s Prayer (ca. 1890) by James Tissot.

I also find it striking that, when the Pharisees challenge Jesus for letting his disciples “thresh” on the Sabbath, his riposte is not You made that version of the commandment up (as it is in one or two other places). He goes instead with a far more provocative three-pronged answer:

- “David broke the Torah,” implying so it’s fine if my disciples do too.

- “Priests break the Sabbath every week for the Temple’s sake, and something greater than the Temple is here”—a buck-wild thing to say among practicing first-century Jews. (Curiously enough, this is also an argument unique to Matthew’s account.)

- Weirdest of all, “The Son of Man is Lord of the Sabbath.” Which, just, what?

None of these rebuttals address themselves to what, on “hedge bad” premises, is the central problem with the Pharisees’ stance: the falsehood of the Oral Torah. Because think it out: if the Oral Torah and the claims made for it were all or mostly false, then its very existence would be a colossal violation of the commandment “Thou shalt not take the Name of the Lord thy God in vain.” Yet on the contrary, all of Jesus’ replies implicitly accept the Pharisees’ premises, and then claim an exemption from them (not unlike another set of verses that in their way are equally shocking9).

Outroduction to the Midtroduction

14th-c. miniature of the Havdalah, the ritual

which concludes the Sabbath,

from the Barcelona Haggadah.

Okay. That was a lot; let’s not summarize it, because I again would prefer not to. What I do want to do is close on two things. The first is a reminder of the Biblical meaning of the Sabbath—not the laws, the meaning, which those laws were designed to protect: The Sabbath is a window onto eternity.

The second is an analogy, one I’m planning to return to as we go from the Judaic week to the Christian. It’s a weird one, but try it for me.

The tempo of the Biblical week is like a tune written for strings, with two strange qualities. First, it’s in 7/8 time,10 though in every measure, the strings section only plays on the first six beats; the seventh is always a rest. And second, you notice—because, if you learned nothing else from that one aunt who was into musicals to a degree that was honestly sort of uncomfortable, you learned your solfège—that the tune rises up from do like most tunes, and resolves back to it like most tunes, but it’s always back down to do—never up to the same note in the next octave.

No, wait, make that three things. This tune isn’t only for strings. Faintly, as if from a distance, you catch the drone of a pipe organ: a literal drone, i.e. always on the same note (do, as it happens), which was why you missed it at first. Meanwhile the violinists, violists, cellists, and bassists are progressing from chord to chord—chords that, you begin to realize, are always either built on the organ’s note or else resolve to it.

Next time, we will go to the next octave. Happy New Year, everybody.

Footnotes

1E.g., in the estimations given for the measurements of the bronze laver in II Chronicles 4:2, we see the Biblical figure for π is 3. Obviously this is a round number; still, the ancient Israelites were in contact with peoples whose mathematics were far more sophisticated than this (for example, the Phoenicians, engineering and navigational geniuses—it is probably no coincidence that when Solomon wanted a temple built, he got a Phoenician to do it for him). The conventional Egyptian value for π appears to have been 256/81 (≈3.16), while the Babylonians often used the handier 25/8 (3.125).

2St. Augustine believed that the “light” created on the first day was metaphorical and referred to the creation of the angels, and that those angels who fell did so more or less immediately. The separation of “Day” from “Night” was, in his view, the division of the holy angels from the corrupt.

3I know of no reason the Torah couldn’t contain both straightforward history and fabrications; however, two words of caution are in order. First, when I say “fabrications,” I’m talking in the same sense that Jesus’ parable of the sower is “fabricated”: it’s fiction, not lies; there’s a difference in intent between those two categories. And second, in my opinion, this becomes little more than a way to try and weasel out of intellectual embarrassment when it’s invoked chiefly or solely to explain miracles. That’s not what it’s for. Literary and stylistic criteria, not the presence of supernatural or inexplicable events, set fabricated object lessons apart from more grounded narrative.

4Thou shalt not kill comes fifth in the form of the Decalogue used by Catholics and Lutherans. Most Protestants treat Thou shalt have no other gods before me and Thou shalt not make unto thee any graven image as commandments one and two, and count Thou shalt not covet thy neighbor’s wife and Thou shalt not covet any thing that is thy neighbor’s as the single Tenth Commandment; following St. Augustine, Catholics and Lutherans combine the former pair and divide the latter.

5“Putting on the finishing touch” is the core idea here. For this reason, it covers not only literally finishing something, but also things like tuning instruments (bringing them back to a “perfected” state).

6However, while I’m not sure—since I’m not only not a rabbi, but also haven’t mastered the far more intricate subject of Star Trek lore—I think using the warp drive would also violate the Sabbath. It sounds as though activating the warp drive, which relied on a reaction between matter and antimatter filtered through dilithium crystals, would be close enough to qualify as the proscribed action of “kneading.”

7The main reason I don’t simply say “It’s anti-Semitic” and have done with it is that, to a lot of people, terms like that are statements not only of effect but of intent. (This is very common on the political Right and in the Center. It’s also truer on the Left than we like to admit, I think.) It might be better if we could excise intent from the word’s connotations; I tend to think it would, though I’m not sure. But either way, intent is among the word’s connotations for the time being, and some concessions must be made to the facts of language as we find them, even if we have great reasons for wishing they were different. (There is also a subordinate, sillier reason. In my own experience, this implicitly anti-Semitic rhetoric tends to be weaponized by evangelicals, not against the Jewish people—for a change, and thank God—but against Catholics. I can’t even be mad about this; it’s too funny to me.)

8To borrow a bit from a YouTuber I like: I feel as though anybody who’s learned even the same modest amount about Judaism as me, read that sentence and said to themselves, maybe out loud, “… Really? Is that how we’re doing it?” And I am sorry, but: Yes, this is how we’re doing it. Look at this long-ass post. I am placing a hedge around this post. I am telling it Thus far and no further, and here shall thy proud point be stayed. I am challenging it to race an ostrich. It’s gotta end somewhere.

9Matthew 23 contains the notorious seven woes against the scribes and Pharisees. The first three verses of the chapter, however, feature Jesus enjoining all disciples to nevertheless obey their halachic rulings, on the grounds that they “sit in Moses’ seat”.

10If you’re not used to dealing with time signatures: aside from 3, any odd number being at the top there is going to have an extremely weird, staggering sound to it. Composers rarely write in these time signatures, no matter how outside-the-mainstream their background and genre may be; like, “What do you mean it’s in 7/8?” is a question Antonio Vivaldi and Sir Mix-a-Lot would be equally capable of posing. There are examples of these rare tempos, like “Take Five,” which is well known for being in 5/4—but they’re rare for a reason! For an example of a real-life song that is (mostly) in 7/8, I suggest “The Rhythm Method” by Flobots.