Divide and eat the lingering hours,

Consume that nourishment of light;

Drink the nectar of evening flowers,

And water from the wells of night.

—Epigraph, Wells of Night

Series Table of Contents:

⇒ Introduction (what sacred/liturgical time is and why we have it)

The Canonical Hours (the Catholic “clock”)

The Former Holy Week (pagan antecedents of the week)

The Seventh Day (the Judaic week and the Sabbath)

The Revelation of the Octave (the Catholic week)

To Everything There Is a Season (Easter computus; fourfold interpretation of Scripture)

The Waxing of the Sun (the literal/meteorological year; the yearly allegory of the life of Christ)

The Waning of the Sun (the spiritual life through the lens of the year)

A Time to Get, and a Time to Keep (liturgical seasons in the Anglican Use)

Weary Se’n-nights Nine Times Nine

Since I revamped the blog last autumn, I’ve more or less followed the liturgical year in my content. However, I haven’t touched much on Christianity’s relationship to time. Here, near the beginning of liturgical year 2025, I’d like to take a little while to do so.

Originally, I had envisioned this post just as a review of the liturgical seasons (of which, depending on how you count them, there are anywhere from three to about sixteen). But, to put the seasons in context, I started writing about calendars more generally. It’s a short step from researching calendars to researching clocks; before you know it, you’re up to your eyes in John A. T. Robinson’s Redating the New Testament to track down his passing reference to a document that’s not even in the New Testament, and trying to decide if it’s worth it to explain the precession of the equinoxes.

A depiction of the sun and moon, who have just

about had it had it up to here with my bull by

now, in the Nuremberg Chronicle (1493).

Point is, I actually bit off a lot more than I could chew with the casual thought “what if explain calendar” (intercalaries: not even once). So, this’ll be the first post in a series!

Entering Sacred Time

Disclaimer: Expressions like “sacred time” can put a person’s hackles up if they’ve heard such names as Joseph Campbell or Mircea Eliade cited with an air of reverence once too often. However. To any of my readers for whom that’s true, I’d like cordially to invite you to get over it. Yes, a lot of anthropologists have handled their own subject with the aplomb, humility, and intellectual modesty of Dr. Jordan B. Peterson’s wardrobe; the same thing is true of every other academic field; reality bites, you’re welcome.

Most cultures set certain things aside as sacred; indeed, the concept of sacredness is so universal that it is hard to articulate (the old “ask a fish to describe water” problem). The best, or at least the simplest, way to convey the idea of sanctity might be to say that it has two subjectively-perceived qualities, usually very strongly: otherness, and importance. The latter quality has some wiggle room: Things that are trivial do not feel sacred, or, if they do, their triviality immediately takes on a paradoxical quality. It feels strange or funny for something sacred to also be in any sense unimportant.

A woodcut depicting Moses removing his sandals

before the burning bush theophany, from a

16th c. edition of the 14th. c. work Speculum

Humanæ Salvationis.

But the “center of gravity” for sacredness as an idea lies more in its aura of otherness. Being unknown or incomprehensible can be an element of this otherness (and the greater the sanctity, the likelier we are to encounter this “cloud of unknowing”), but it is not only an intellectual quality. It carries with it a sense of not “playing by our rules,” both in the practical sense of not being able to predict the behavior of the sacred or enforce human standards of behavior upon it, and also in a more mysterious sense almost of not having rights in its presence, of being “out of one’s depth” or “outranked” in a moral or ontological sense as well as the mental sense.

In particular, the sphere of “the religious”—a term which smarter and better-educated people than me have tried and failed to define—is apt to designate certain places as holy: the shrines, temple precincts, sacred grottoes, and forbidden mountains of religions the world over. In those places, when they can be visited at all, the rules of behavior are usually different from what they are outside, usually either on the grounds that the pertinent deity requires these differences, or (more boringly) in order to evoke and foster an atmosphere of sacredness.

Sacred time is to the rest of time what sacred places are to the rest of space. Following a precedent established by the Hebrew calendar, the Christian liturgical calendar attempts the sanctification of all time—not in the sense of doing away with the distinctions between sacred and profane, but, as with the discussion of “trivial sanctities” above, by awakening a paradoxical sense of universal otherness, as it were.

In the late 1930s, Charles Williams, one of the less-famous Inkling-adjacent authors, wrote a commendable, strange, useless, brilliant account of Christian history, titled The Descent of the Dove. It opens like this:

The beginning of Christendom is, strictly, at a point out of time. A metaphysical trigonometry finds it among the spiritual Secrets, at the meeting of two heavenward lines, one drawn from Bethany along the Ascent of Messias, the other from Jerusalem against the Descent of the Paraclete.1 That measurement, the measurement of eternity in operation, of the bright cloud and the rushing wind, is, in effect, theology.

The history of Christendom is the history of an operation. It is an operation of the Holy Ghost towards Christ, under the conditions of our humanity … The visible beginning of the Church is at Pentecost, but that is only a result of its actual beginning—and ending—in heaven. … They had not the language; they had not the ideas; they had to discover everything. They had only one fact, and that was that it had happened. … “It is!” they said, but then they had to go on saying “It is!” Time existed, and time itself had, as it were, to be converted, to be rededicated towards the thing out of time. … How, and how far, do we pass out of time? The apostates are only those who abandon the problem; the saints are only those who solve it.2

Expositions of the Mystery

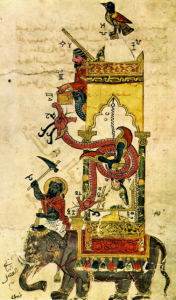

A depiction of an elephant clock (apparently

a type of water-clock!) in Ismail al-Jazari’s

Book of Knowledge of Ingenious Mechanical

Devices, first published in 1206.

Practically speaking, Christianity (like mankind, its mother) tracks time on multiple levels, governed primarily by means of the sun and moon. This is their ostensible purpose, Scripturally:

And God said, “Let there be lights in the firmament of the heaven to divide the day from the night; and let them be for signs, and for seasons, and for days, and years: and let them be for lights in the firmament of the heaven to give light upon the earth”: and it was so. And God made two great lights; the greater light to rule the day, and the lesser light to rule the night: he made the stars also. And God set them in the firmament of the heaven to give light upon the earth, And to rule over the day and over the night, and to divide the light from the darkness: and God saw that it was good. —Genesis 1:14-18

The Christian schema makes use of three temporal cycles. Two, the day and the year, are solar; the third, the week, may originally have been lunar (approximating the transition from one of the moon’s “cardinal” phases3 to the next), though it has long since been detached from any actual changes in the moon.

Clock face from the Marienkirche in Lübeck, Germany.

You may notice that the month is conspicuously absent from the liturgical analysis here. Its origins are certainly lunar—you can even see the name as a slightly worn-down version of “mooneth.”4 The month did and does play a role in the Hebrew calendar; however, months are of minimal importance to Christian practice. Their place has been more or less handed over to seasons. But, since no liturgical season except Easter has an exactly set number of days, and (as far as I’ve been able to discern) there is no underlying structure that all liturgical seasons share with each other, it isn’t really possible to speak of months being “reworked” into seasons or anything along those lines.

To recap, these are the kinds of sacred time we’ll be looking at:

- The day is measured mostly from sunrise to sunrise.5 The Christian day is subdivided into around seven canonical hours, a topic we’ll come back to momentarily.

- The week consists in seven full days, usually reckoned from Sunday as the first. Days can be classified in a few different ways, but we’ll analyze this at greater length in a later post.

- The other solar cycle is the year: one year is the amount of time it takes the Earth to complete one orbit around the sun.6 The civil year used by most cultures is divided twelve or thirteen months, while the Catholic year is divided into about five principal liturgical seasons, plus a large host of secondary and ancillary quasi-seasons.

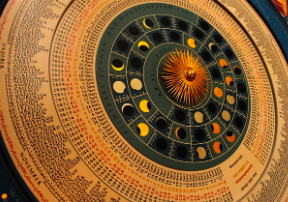

A 16th-cent. Tibetan mandala of the Kālacakra

or “wheel of time.” This is not particularly like

the Catholic ritual year in any way; it is,

however, very pretty.

Through the canonical hours, the Christian week, and the liturgical year, the Church proposes to make time the vehicle of eternity. The strength of this idea is suggested by C. S. Lewis, speaking through the mouth of Screwtape in his eighth letter to Wormwood:

Has no one ever told you about the law of Undulation? Humans are amphibians—half spirit and half animal. (The Enemy’s determination to produce such a revolting hybrid was one of the things that determined Our Father to withdraw his support from Him.) As spirits they belong to the eternal world, but as animals they inhabit time. This means that while their spirit can be directed to an eternal object, their bodies, passions, and imaginations are in continual change, for to be in time means to change. Their nearest approach to constancy, therefore, is undulation—the repeated return to a level from which they repeatedly fall back … If you had watched your patient carefully you would have seen this undulation in every department of his life—his interest in his work, his affection for his friends, his physical appetites, all go up and down. … The dryness and dullness through which your patient is now going … are merely a natural phenomenon which will do us no good unless you make a good use of it.

Coming up next: a deep(er) dive into the canonical hours that structure the sacred day.

Footnotes

1“Paraclete” is a title of the Holy Ghost; it transliterates the Greek term most Bibles render “comforter,” “advocate,” or “helper.”

2Descent pp. 1, 3, 15 (italics in the fifth sentence of the second paragraph are original).

3I.e., the new, quarter, and full moons. The crescent and gibbous phases technically cover the whole period between these cardinal phases,

4To be clear, this isn’t really an ancestral form of the word “month.” The Middle English (and modern Scots) form was moneth, from Anglo-Saxon ᛗᚩᚾᚪᚦ [mōnath]—its final -th is not the third-person singular verb ending we see on doth or worketh, but a now-obsolete ending for making verbal nouns (one that also appears in words like growth, stealth, or, though differently pronounced, weight). However, its ultimate Proto-Indo-European root seems to be a derivative of a verb (one meaning “to measure”), and it felt only just to get the name of the Moon in there, so I adjudged the pseudo-antique form was justified for illustrative purposes.

5That is, in practice. In principle, the Biblical day begins at sunset, which is why vigil Masses are a thing. However, the principle is inconsistently applied—for example, in Catholic prayer books, Sundays and solemnities normally feature a First and Second Vespers/Evening Prayer/Evensong, one for the evening preceding the holy day and one for the evening following.

6That’s how we describe it now. Obviously this was not known before heliocentrism, but they were still able to measure the length of a year to a high degree of accuracy, by a quite different means. If you watch where on the horizon the sun rises from in most of the northern hemisphere, you’ll notice that the sun gradually creeps southward over July through November, reaching its furthest-south “point of origin” on the winter solstice. After that, it reverses, rising from horizon-points further and further north until the summer solstice, and then heads south again. The reason the sun “moves” like this is because of the tilt of the Earth’s axis, which in turn makes sense. I imagine.