The Last Gospel

Happy post-Thanksgiving, everyone! In the spirit of the holiday, I’d like to share the “General Thanksgiving” used in the Ordinariates (which of course derives from the Book of Common Prayer of the Anglican Communion).

A male turkey in Marin County, CA. Photo by

Frank Schulenberg, used under a CC BY-SA

4.0 license (source).

Now, I feel that the flowing cadences of the Prayer-book style of English can kind of lull the mind and make the meanings of the prayers … well, not hard to understand, exactly—more easy to miss. Therefore, to help highlight its meaning a little, I’ve printed this prayer in a slightly unusual format. It’s not a full-blown sentence diagram or anything, just (I hope!) a visual aid.

Below, various phrases are indented to different amounts. Phrases indented the same amount all depend on whichever line above them is one step less indented. For example: the sixth and seventh lines (“for our creation …” and “but above all …”) are both elaborations based on the fifth line (“We praise thee”), and so are the ninth and tenth lines (“for the means …” and “and for the hope …”); however, the eighth line (“in the redemption …”) is a further explanation of the seventh, so it gets an extra step of indentation.

Almighty God, Father of all mercies,

we thine unworthy servants

do give thee most humble and hearty thanks

for all thy goodness and loving-kindness to us, and to all men.

We praise thee

for our creation, preservation, and all the blessings of this life;

but above all, for thine inestimable love

in the redemption of the world by our Lord Jesus Christ,

for the means of grace,

and for the hope of glory.

And we beseech thee,

give us that due sense of all thy mercies,

that our hearts may be unfeignedly thankful,

and that we show forth thy praise, not only with our lips, but in our lives;

by giving up ourselves to thy service,

and by walking before thee in holiness and righteousness all our days;

through Jesus Christ our Lord, to whom with thee and the Holy Ghost

be all honor and glory, world without end. Amen.

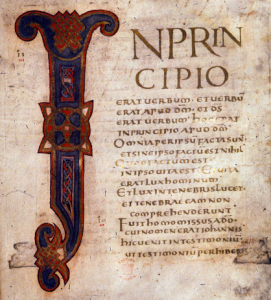

Now then! “The Last Gospel” is a name for (most of) the prologue of the Gospel of John.1

The first page of John in the Athelstan

Gospels, created in the late 9th or early 10th

century and given to Athelstan, generally

held the first King of England (r. 924-939).

That’s not what we’re talking about here.

Christ the King

We’re talking about the text designated for the Solemnity of Christ the King, which is ipso facto always the final Sunday Gospel of the liturgical year, and was therefore observed this past Sunday.

This solemnity is of very recent origin; it was instituted by Pope Pius XI in 1925, through the encyclical Quas Primas. Between 1917 and 1925, four monarchies (the imperial houses of Austria, Germany, Russia, and Turkey) had fallen; moreover, three large countries had become Communist and thus officially atheistic (Mexico, Mongolia, and of course Russia itself). The use of outdated royalist symbolism for this solemnity, in what was, even then, an increasingly nationalistic and anti-monarchist world, was doubtless pointed on His Holiness’ part. It isn’t that he was interested in wedding the Church to expired political causes. Quite the contrary: Pius XI was the pontiff who finally negotiated a compromise with the Kingdom of Italy on the status of the papacy, thus establishing Vatican City as a sovereign state; the year after Quas Primas, he outright condemned the French royalist movement Action Française, which was what we’d call “culturally Catholic” (though led by an agnostic). But he did not trust democracy or desire it for its own sake, any more than he trusted Communism.

Madonna on a Crescent Moon in Hortus Conclusus,

c. 1450, by an anonymous painter from Cologne.

Hortus conclusus means “enclosed garden”; the

phrase occurs in the Vulgate in Song of Songs 4.12.

His Holiness was also avowedly hostile to nationalism and racism (tendencies which this Solemnity implicitly rebukes). He encouraged the ministry of St. Katharine Drexel to Black and Native Americans in the US, and it is also to him that we owe the following:

Mark well that in the Catholic Mass, Abraham is our Patriarch and forefather. Anti-Semitism is incompatible with the lofty thought which that fact expresses. It is a movement with which we Christians can have nothing to do. No, no I say to you it is impossible for a Christian to take part in anti-Semitism. It is inadmissible. Through Christ and in Christ we are the spiritual progeny of Abraham. Spiritually we are all Semites.

This comes from an address the pope gave to a group of pilgrims in Belgium in 1938 (the year after he issued the famous encyclical Mit Brennender Sorge, which condemned not only Hitler’s incessant violations of the rights he had guaranteed the Church, but Nazi racial ideology). It does not wipe away the history of Catholic anti-Semitism, no matter how much some Catholic apologists would like it to. What it does do is express a badly-needed course correction in the Church’s relationship to modern culture, by succinctly and clearly articulating exactly why Christian anti-Semitism—despite how plentiful it is and has been—was always, and remains, nonsensical to the point of shamefulness.

Now, let us turn to the Gospel for this solemnity. As usual, parts of the text not read at Mass but which I’ve translated anyway are printed in grey instead of black.

John 18:33a, 33b-37, RSV-CE

Christ Carrying the Cross (1580), by Domenikos

Theotokopoulos (a.k.a. El Greco)

Pilate entered the praetorium again and called Jesus, and said to him, “Are you the King of the Jews?” Jesus answered, “Do you say this of your own accord, or did others say it to you about me?” Pilate answered, “Am I a Jew? Your own nation and the chief priests have handed you over to me; what have you done?” Jesus answered, “My kingship is not of this world; if my kingship were of this world, my servants would fight, that I might not be handed over to the Jews; but my kingship is not from the world.” Pilate said to him, “So you are a king?” Jesus answered, “You say that I am a king. For this I was born, and for this I have come into the world, to bear witness to the truth. Every one who is of the truth hears my voice.”

John 18:33a, 33b-37, my translation

Then Pilate came back into the prætorium and called Jesus and said to him: “You are the king of the Jews?” Jesus responded, “Are you saying this on your own, or did others tell you about me?”

Pilate responded, “I am not a Jew, am I? Your nation and high priests have handed you over to me; what did you do?” Jesus responded: “My kingship is not from this world; if my kingship were from this world, my attendants would be striving, lest I be handed over to the Jews; but now my kingship is not from the here and now.”

So Pilate said to him, “Then, you are a king?” Jesus responded, “You say that I am a king. For this I have been begotten and for this I have come into the world, in order to testify to the truth; everyone who is from the truth hears my voice.”

Textual Notes

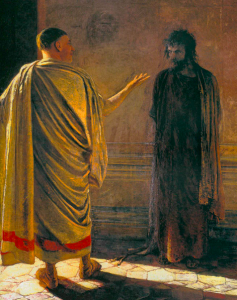

What Is Truth? (1890), Nikolai Ge

a. prætorium: A prætorium was, in origin, more or less the “HQ” of a Roman military camp. By the first century, the term was used a bit more loosely, as it is here: the province of Iudæa was not in the process of being conquered, but had peaceably changed hands decades before. (Its last native king—or more strictly, ethnarch2—had been Herod Archelaus, a son of Herod the Great, who like his father before him had been propped up by Roman power. In about 6 CE, the Romans deposed Archelaus for cruelty and incompetence and assumed direct rule of the region, placing it under a series of prefects, of whom Pilate was the fifth.)

b. servants/attendants: The Greek term here, ὑπηρέτης [hüpēretēs], is rather interesting. In first-century Greek, it is not firmly distinguished from other words for “servant,” though it was first coined to describe the rowers in a ship. However, it occurs in a good many other places in the Gospels and the book of Acts (eight other times in John, twice in each of the Synoptics, and four times in Acts, according to Mounce); and in these instances, ὑπηρέτης nearly always refers to guards of some kind, or to officials who commanded or oversaw guards. This could lead to a sort of sarcastic reading of Jesus’ remark—something approaching “If I’m a king, then where’s my bodyguard?”

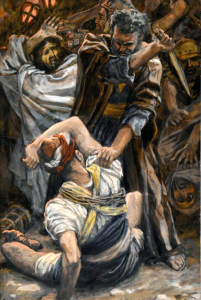

The Ear of Malchus (between 1886 and

1894), James Tissot

With or without that reading, it is also interesting to juxtapose this with an event that occurred only a couple dozen verses ago: in John 18:10-11, St. Peter pulls out his sword and very much does “strive, lest he be handed over to the Jews,” to the point of cutting off the ear of Malchus, one of the high priest’s slaves. (True, Jesus promptly heals Malchus,3 but still, that counts as striving.) Especially in light of the rebuke at Cæsarea Philippi,4 this can be read not merely as a statement of fact on Jesus’ part, but as an implicit definition or command—asserting that, insofar as anyone does try to prevent the Passion, they are, however unwittingly, working against God.

c. the Jews: Here, I am noting a problem only to almost immediately lay it down again unsolved. I don’t have adequate time right now to do justice to it; I’ve been working on a piece that I hope will begin to do justice to it for some months, but that piece is not yet done. However, I wouldn’t feel right passing over the matter in silence.

The New Testament has been accused of being an anti-Semitic collection of texts, particularly the Gospels and Acts. Whether that is a fair assessment or not, it’s absolutely true that anti-Semitism has been rationalized and promoted on New Testament pretexts, and still is. Accordingly, any discussion of this topic by Christians needs to be handled with extreme delicacy, for one practical reason and one reason of plain human decency.

Talmud Readers (c. 1920-1935?), Adolf Behrman

The practical reason is that it’s easy, by careless phrasing, to say things certain vile people will adopt into their anti-Semitic repertoire. None of us should want to give these people a BB pellet’s worth of additional ammo: their ideology is detestable, absurd, and blasphemous.

The human-decency reason is this. In the sociological sense, the principal source of anti-Semitism in history is Christians.5 No, I don’t mean the Christian faith is to blame (I’m actually planning to make a case that it’s not, in my aforementioned incomplete post). But it doesn’t need to be the fault of Christianity to be the fault of Christians. The phenomenon of trade, just as such, was not to blame for spreading the Black Death in the fourteenth century; rat fleas were. It’s nonetheless true that the Black Death spread along trade routes throughout Eurasia, particularly the Silk Road, because trading caravans are apt to carry rats and rats are apt to carry rat fleas—so that there’s absolutely a sense in which trade was a contributing cause of that pandemic. And the place where this analogy falls down only makes Christians looks worse, because unlike us, fourteenth-century silk traders could at least truthfully plead that their contribution to the mass death was unwitting and unwilling.

The upshot of this is, Christians need to deal with questions like “Is the New Testament anti-Semitic?” with a great deal of tact and humility; something we do not, as a rule, extend to our elder brethren particularly often. We extend them affection relatively easily nowadays. I dare say this would be more sufferable of us, if we had not cheerfully forgotten our own history while we were at it. But even if we hadn’t, displays of unasked affection are not always welcome, and it is really not the affection-giver’s place to decide how the recipient shall respond. It is our duty to bear in mind both the practical danger of incautious speech, and the fact that, speaking about the Church collectively, there is blood on our hands. Our individual innocence of that blood means something, but only so much.

Though justice be thy plea, consider this,

That in the course of justice none of us

Should see salvation.

—The Merchant of Venice, IV.1.cxcviii-cc

d. the world/the here and now: “The here and now” is my compromise-translation of ἐντεῦθεν [enteuthen]; really I should have picked one—”from here” or “from this age” would both have been defensible renderings. The term, and the text, are ambiguous, but I can’t produce a strictly linguistic justification for pulling in both meanings for my translation.

e. was born/have been begotten: “I was born” is a perfectly correct translation of γεγέννημαι [gegennēmai]. What that translation downplays, though, is the (indirect) relationship between this verse and John 1:18, which uses the related adjective μονογενής [monogenēs] in this way: “No one has ever seen God; God the μονογενής, who is at the Father’s side—he has disclosed him.” Though often translated “only,” a more literal rendering of μονογενής is “only-begotten.”

f. who is of the truth/who is from the truth: I could have sworn this same grammatical point came up in one of my recent posts, but then I couldn’t find it when I looked. Anyway, the Greek phrase here is ὁ ὢν ἐκ τῆς ἀληθείας [ho ōn ek tēs alētheias], and it’s rather unusual. Instead of using a normal verb in this clause, like ἐστί [esti] for “[he/she/it] is,” John’s author uses a participle, ὢν—”is existing” would be the flat-flooted version. Now, “who is existing from the truth” is an impossibly awkward phrase in English; no one would ever say that. But I wanted to convey some measure of the strangeness it has, and also to correct a bit for what the RSV’s version seems to me to suggest. To “be of the truth,” to me, suggests a kind of partisanship, a “siding with” the truth; what the text hints at is more like a metaphysical relationship. The phrasing “is from” seemed like the closest I could easily approach to these hints without making them more emphatic or explicit than the text really justifies.

Footnotes

1The full prologue is John 1:1-18; the selection used as “the Last Gospel” ends with verse 14.

2An ethnarch was the ruler of an ethnic group or ethnically homogeneous region (derived from the Greek ἔθνος [ethnos], “people, nation, tribe”). Ethnarchs were usually subordinate rather than fully autonomous rulers.

3All four evangelists relate the story of Malchus’ ear being cut off. Three of them—Matthew, Mark, and John—are traditionally considered to have been written by definite or possible eyewitnesses of the event (whether Mark was there is iffy, but in any case he’s supposed to have gotten his scoop from Peter). Only Luke, the one canonical evangelist who definitely wasn’t there, mentions that Jesus immediately healed Malchus. That fact can be taken a few different ways; there is no proof of my preferred way to interpret it, which is that the disciples who were there didn’t feel comfortable mentioning that this terrible thing one of them had done was immediately put right.

4I.e., the “Get thee behind me” spoken to Peter (see Matthew 16:23 and Mark 8:33).

5Anti-Semitism in the ancient world was not common: cultural snobbery there certainly was, but, apart from the persecution of the Seleucids that prompted the Maccabean Revolt, hatred of Judaism as a religion or of the Jews as a people was not normal. (Even during the Jewish Wars, Jews in other parts of the Roman Empire were not subjected to generalized persecution—that only started under the Christian emperors.) As for the modern world, it may possibly be true that a numerical majority of anti-Semites have been non-Christians by creed, fascistic or Communist as the case may be. And? Where are we meant to suppose those ideologies got their anti-Semitism, if not from the Christianized cultures of central Europe in which both arose?