The Olivet Discourse

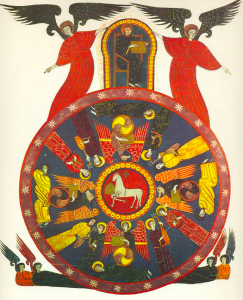

Vision of the Lamb among the cherubim

(Revelation 5) from Beatus of Liébana‘s

commentary on the Apocalypse

The Olivet Discourse is associated more with the Gospel of Matthew than that of Mark, or Luke’s for that matter. Matthew’s version, to which four apocalyptic parables are appended (those of the servant who does not expect his master’s return, the wise and foolish bridesmaids, the talents, and the sheep and the goats), is by far the longest. This address is called the Olivet Discourse for two reasons:

- It is described as being given on Mount Olivet, or the Mount of Olives, a ridge to the east of Jerusalem. Curiously, it was apparently given in private to the bar-Zebedee and bar-Jonah brothers alone (i.e. James, John, Peter, and Andrew); why the other eight were not present, or perhaps not invited, isn’t made clear.

- It is the fifth of the Five Discourses contained in the Gospel of Matthew.1 Though they may represent teachings that Jesus delivered as the text represents, it’s also possible that they are more along the lines of “themed compendia,” stitched together from teachings given at various times throughout his ministry; that there are five (each of which is concluded with the distinctive phrase “when Jesus had ended these sayings”) is widely accepted to be a nod to the Five Books of Moses2—part of Matthew’s broader depiction of Jesus as the new Moses.

On the whole, and setting aside the parables Matthew contains, the two versions of the Olivet Discourse are far more similar than different. Mark leaves out a handful of details. (The direct parallel to this past Sunday’s reading from Mark is Matthew 24:29-36.) A couple were small “wrinkles” or descriptive elaborations: Matthew tells us that “the sign of the Son of Man will appear in heaven, and all the tribes of the earth will mourn” before the appearance of the Son of Man himself “coming on the clouds,” and also adds that the angels who go to gather up the elect will be sent “with a loud trumpet,” whereas Mark omits both details.

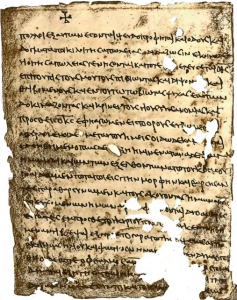

The beginning of a fragment of the Apocalypse

of Peter, one of a few works which were

considered for inclusion in the New Testament

but ultimately rejected by the Church.3

However, I’m rather struck by one difference. The Matthean parallel to Mark 13:24 is Matthew 24:29; and the latter verse begins with the adverb εὐθέως [eutheōs], “immediately,” a derivative of εὐθύς [euthüs], “direct” or “straight.” Now, if the author of Mark has a favorite word, it’s εὐθύς: he uses it thirteen times just in the first two chapters of his Gospel. I therefore find it quite odd that Matthew would have a form of this word in a place where Mark doesn’t have it (or even have a synonym), when the two are otherwise so close to each other verbally, sometimes verbatim. I don’t know what this implies, if it implies anything at all; but, something to file away—or, to use a more Biblical idiom, a thing to treasure up and ponder in one’s heart.

Mark 13:24-32, RSV-CE

“But in those days, after that tribulation,a the sun will be darkened, and the moon will not give its light, and the stars will be falling from heaven,b and the powers in the heavensc will be shaken. And then they will see the Son of man coming in clouds with great power and glory. And then he will send out the angels,d and gather his electe from the four winds, from the ends of the earth to the ends of heaven.

“From the fig treef learn its lessong: as soon as its branch becomes tender and puts forth its leaves, you know that summer is near. So also, when you see these things taking place, you know that he is near, at the very gates. Truly, I say to you, this generationh will not pass away before all these things take place. Heaven and earth will pass away, but my words will not pass away.

“But of that day or that hour no one knows, not even the angels in heaven, nor the Son, but only the Father.”i

Mark 13:24-32, my translation

Central panel from The Last Judgment

(c. 1482), a triptych by Hieronymus Bosch.

“But in those days, after that distress,a the sun will be darkened, and the moon will not give her splendor, and the stars will be falling out of heaven,b and the powers that are in the heavensc will be shaken. Then also they will see the Son of Man coming among clouds with much power and glory; and then he will commission the messengersd and gather up those selectede from the four winds, from the end of the earth to the end of heaven.

“From the fig,f learn this analogyg: at whatever time its shoots become soft and put forth leaves, you know that summer is near; in the same way you will also know, whenever you see these things, that he is near—at the doors. Amen, I tell you that this generationh will not pass on, not until all these things occur. Heaven and the earth will pass on; my words will not pass on.

“Yet no one knows about that day or hour, neither the messengers in heaven nor the Son, except the Father.”i

Textual Notes

a. tribulation/distress: A hyper-literal translation of this word would be “pressure.”

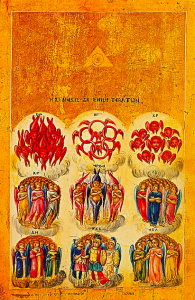

An Eastern ikon of the nine orders of angelic

beings, arranged beneath the Godhead

represented as a triangle.

b. will be falling from heaven/will be falling out of heaven: This is rather an odd way to phrase it. Put into the same word order as the Greek, it does hyper-literally say, not “[they] from the heaven will-fall,” using a normal future-tense verb, but “[they] will-be from the heaven falling” (ἔσονται ἐκ τοῦ οὐρανοῦ πίπτοντες [esontai ek tou ouranou piptontes]), with the participle. This doesn’t necessarily strike our ears as that strange, because a lot of English tenses habitually use participles. If you get a call in the middle of dinner and need to explain why you can’t talk at the moment, you don’t use the simple present, “I eat”; you replace it with a being verb plus a present participle and say: “I am eating.” This is not the normal way to speak or write in Greek (or most languages4). This might indicate, then, that what’s being depicted here is a period rather than an event—a period characterized by “stars falling from heaven” being commonplace.

c. the powers in the heavens/the powers that are in the heavens: This phrase, like “the prince of the power of the air” (Ephesians 2:2), seems to mean fallen angelic beings. It is possible that Jesus means specifically what we mean by “the Powers”—i.e., the sixth of the nine choirs, generally held to have influence over the development of history—but this is not necessarily the case; Judeo-Christian5 angelological terminology does not appear to have been at all settled at this time.

d. angels/messengers: Neither Greek nor Hebrew had a special word for these beings. English has one simply because Latin borrowed the Greek word for “messenger” when it means these beings; thus, ἄγγελος [angelos] became angelus, and we borrowed the Latin word. (This does mean that it is technically an interpretation, rather than a translation, every time we find the word “angel” in our Bibles; however, for contextual reasons, this puts the reader in danger of misreading an ambiguous passage less often than you might think.)

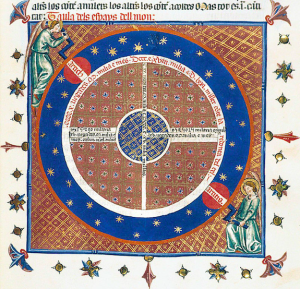

14th-cent. depiction of angels turning the

celestial spheres, possibly by a Catalan

illuminator.

e. he will send out the angels, and gather his elect/he will commission the messengers and gather up those selected: There are a few minor nuances here that get lost in translation; for instance, the verb the RSV renders as “send,” I decided to make “commission,” because it is the same verb from which we get the noun “apostle” (i.e. emissary). The “messengers” here, given what they are commissioned to do, are fairly clearly angels—this is a good example of why confusing ordinary earthly messengers with angelic beings is not actually that common.

Also, fun aside about the word for “elect” or “selected,” which is ἐκλεκτοὺς [eklektous]. This does mean “chosen,” or, hyper-literally, something like “counted out”; it is also the root of the word eclectic. “Eclecticism” was originally a term in ancient philosophy, denoting systems that blended elements from multiple schools of thought. Cicero was an eclectic philosopher in this technical sense, combining ideas from the Aristotelian, middle Platonist, and Stoic schools of thought. Similarly, Neoplatonism (formulated in the third century by Plotinus and his disciple Porphyry) was an eclectic version of Platonism, synthesizing Aristotelian, Pythagorean, Stoic, and possibly Judaic elements. Christian Neoplatonism was obviously eclectic as well.

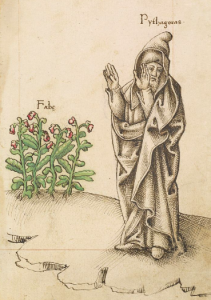

An early 16th-cent. French drawing of

Pythagoras and some fava bean plants

(notoriously, Pythagoras and his followers

refused to eat beans of any kind).

But returning to our text: As with many apocalyptic prophecies, it’s kind of difficult to say for certain what this passage means. It sounds like angels will be sent around, literally plucking humans off the face of the earth like a kid picking the chocolate chips out of a loaf of banana chocolate chip bread. And who knows, maybe that is how it’ll work! Judging from certain passages in Revelation, and a few cryptic tidbits elsewhere in the New Testament, angelic intelligences do have some kind of active engagement in the affairs of the earth at large, and especially the Church. I find myself unable to say more than that.

f. From the fig tree/From the fig: It’s possible, though not certain, that this is an allusion to two chapters earlier, where Mark records the blasting of the fig tree. Mark places the most emphasis on the story (and is the only one to take note of the fact that Peter was the one to point out that the fig had withered): it is absent from John; Luke hints at the idea in a parable; Matthew includes a shorter and less detailed version of the event. Only Mark records that the cursing and the withering took place on two consecutive days—just as only he records that the triumphal entry and the cleansing of the Temple took place on two different days. Perhaps, if the day of the triumphal entry was a sabbath, either the stalls in the Temple were not operational (the likelier reason, I think) or it might be that Jesus would not practice even such moderated violence as was involved in cleansing the Temple on the sabbath.

Clockwise: barley, dates, grapes, figs,

pomegranates, olives, and wheat. Author

not named; used under a CC BY-SA 4.0

license (source).

Fig trees, like vineyards and plots of wheat, were sometimes symbols of the Jewish people in the prophets. All these crops were among the sacred “seven species”: barley, dates, figs, grapes, olives, pomegranates, and wheat. According to the Torah,6 these crops characterized the land of Israel and were in some sense part of the promise. The first-fruit offerings on Passover and Pentecost were of barley and wheat respectively, and most rabbis in Jesus’ day seemed to be of the opinion that first-fruit offerings in general could only be licitly given from the seven species. Dates and barley do not play major symbolic roles in Scripture (that I know of), save for the mention in John 6 that the bread which fed the five thousand was barley bread, as we have touched on before. However, thanks to its oil, the olive was important for lamps and soaps as well as food; the pomegranate featured in the imagery of the Temple (e.g., the lower fringe of the high priest’s garments was lined with alternating bells and woven pomegranates, the latter in blue, purple, and scarlet); and of course the grape was used to make wine, which was essential to both sacrifices and feasts.

g. lesson/analogy: It was kind of tempting to translate this word “metaphor,” but I think that would be too much of a stretch! However, παραβολή [parabolē] is, obviously, where we get the word “parable.”7

h. generation: This one is slightly tricky to explain. The Greek word γενεά [genea] does mean “generation,” but it means it a bit more literally than the English does: i.e., it simply denotes “that which is or has been generated.” In English, we’ve imported a temporal aspect, which the Greek word doesn’t necessarily possess. An ethnic group, for example, is a γενεά, just as much as a cohort8 is a γενεά. We don’t have a word in English (or not that I know of) that fits this range of meanings very exactly, so how to render it is a toughie; “generation” is no worse than anything else, and has the advantage of being etymologically sound.

A depiction of the Trinity in the Llanbeblig

Hours (a late 14th-cent. book of hours, now

housed in the National Library of Wales

i. no one knows … nor the Son, but only the Father/no one knows … nor the Son, except the Father: When I first posted this piece, I erroneously stated that only Mark includes “nor the Son” here, but that isn’t true—Matthew also has the phrase (that is, in some manuscripts—it is missing from the Greek of the Textus Receptus, which is why the King James omits “nor the Son” from its Matthew 24:36).

As for the actual intellectual problem of the Son not knowing things the Father knows! For once, I don’t think I accept C. S. Lewis’s solution exactly, which he sets forth in his essay “The World’s Last Night” (in the collection of the same name, or in transcript and audio forms here); Lewis strikes me as too comfortable with the idea of Jesus not only being ignorant, but in fact erring—and those are two different things—on what is, surely, a “matter of faith and morals.” All the same, I think his solution does improve the picture most of us have of Jesus, so I’ll quote a selection from it anyway.

From “The World’s Last Night”

The very name apocalyptic assigns our Lord’s predictions of the Second Coming to a class. There are other specimens of it … and to most modern tastes the genre appears tedious and unedifying. Hence there arises a feeling that our Lord’s predictions, being much the same sort of thing, are discredited. … [But] if we once accept the doctrine of the incarnation, we must surely be very cautious in suggesting that any circumstance in the culture of first-century Palestine was a hampering or distorting influence upon His teaching. Do we suppose that the scene of God’s earthly life was selected at random, that some other scene would have served better?

Saint Joseph Seeks a Lodging in Bethlehem

(ca. 18509), James Tissot

But there is worse to come. Say what you like, we shall be told. The apocalyptic beliefs of the first Christians have been proved to be false. It is clear from the New Testament that they all expected the second coming in their own lifetime, and, worse still, they had a reason … Their master had told them so. He shared, and indeed created, their delusion. He said, in so many words, ‘This generation shall not pass till all these things be done.’ And he was wrong. He clearly knew no more about the end of the world than anyone else. It is certainly the most embarrassing verse in the Bible. Yet how teasing, also, that within fourteen words of it should come the statement, ‘But of that day and that hour knoweth no man, no, not the angels which are in heaven, neither the Son, but the Father.’ The one exhibition of error and the one confession of ignorance grow side by side.

… The facts then are these, that Jesus professed Himself in some sense ignorant, and within a moment showed that He really was so. To believe in the Incarnation, to believe that He is God, makes it hard to understand how He could be ignorant, but also makes it certain that if He said He could be ignorant, then ignorant He could really be. For a God who can be ignorant is less baffling than a God who falsely professes ignorance.

The answer of theologians is that the God-Man was omniscient as God and ignorant as man. This, no doubt, is true, though it cannot be imagined. Nor, indeed, can the unconsciousness of Christ in sleep be imagined … But the physical sciences, no less than theology, propose for our belief much that cannot be imagined. A generation which has accepted the curvature of space need not boggle at the impossibility of imagining the consciousness of incarnate God.

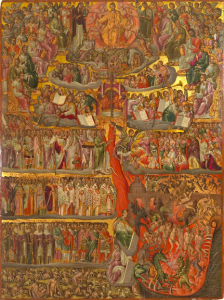

Ikon of the Last Judgment, written ca.

1580-1608 by Georgios Klontzas.

… [I]f limitation, and therefore ignorance, was thus taken up, we ought to expect that the ignorance should, at some time, be actually displayed. It would be difficult and, to me, repellent, to suppose that Jesus never asked a genuine question, that is, a question to which He did not know the answer. That would make of His humanity something so unlike ours as scarcely to deserve the name. I find it easier to believe that when He said, ‘Who touched Me?’ (Luke 8:45), He really wanted to know.

Footnotes

1The other four are the Sermon on the Mount (chs. 5-7), the Mission Discourse (ch. 10), the Parable Discourse (ch. 13), and the Ecclesiastical Discourse (ch. 18).

2The Torah was thought of by the Jews as a single book (and still is), but the fivefold division of it had already been introduced, for a rather amusing reason: the size of a papyrus roll, which was then the prevalent writing material. You could only fit about a fifth of the Torah onto a standard-length papyrus roll (with some variation depending on how large your handwriting was, perhaps), so to keep sets of Torah scrolls from being too inconsistent with each other, standard cutoff points were introduced, and the portions given names: The Beginning, The Departure, Matters for the Levites, Censuses, and The Second Statement of the Law (or in Greek, Genesis, Exodos, Leuitikos, Arithmoi, and Deuteronomion—and for some reason, in English, we decided to translate just the fourth of these titles and leave the rest).

3There are not many of these “New Testament apocrypha,” as they are sometimes called—i.e., there are not many that were seriously considered for inclusion in the Bible; there are a decent number of Christian documents dating to this period (such as the epistles of St. Ignatius of Antioch), which are often, a little misleadingly, grouped together with the NT apocrypha. Other books that were considered by some early Christians to be Scripture include the Didache, the Epistle of Barnabas, the Shepherd of Hermas, and I and II Clement (the former is a letter, the latter part of a homily). Of these, the Didache is the most ancient, and may in fact date back to the period when some of the Apostles were still alive.

4In fact, this way of forming tenses, especially the naturally-common present tense, is so unusual that one theory about the development of English is that this is a trait borrowed/inherited from the Celtic languages that were spoken in Britain before the Anglo-Saxon conquest (because Celtic languages are among at very few that feature this same participial present tense).

5It doesn’t happen nearly as often as most people who like using the term wish to think, but there are contexts, like this one, where “Judeo-Christian” is the best word!

6On some interpretations, the honey with which the “land flowing with milk and honey” flowed was actually date honey, a syrup made by boiling dates.

7And “parabola.” If you were wondering.

8This word has been popularized alongside some fairly silly exaggerations of their importance, but honestly, it’s a good word.

9That is, the painting was executed around 1850. St. Joseph visited Bethlehem seeking lodgings years, if not weeks, before 1850 had even begun.