Prolegomenon

As discussed in my last, this is the next-to-last reading from the Gospel of Mark this year, and falls during the teaching in the Temple that took place in Holy Week. Let’s jump in!

Mark 12.38-44, RSV-CE

Russian ikon of St. Mark (16th c.)

And in his teaching he said, “Beware of the scribes,a who like to go about in long robes, and to have salutationsb in the market places and the best seatsc in the synagoguesd and the places of honorc at feasts, who devour widows’ houses and for a pretense make long prayers. They will receive the greater condemnation.”

And he sat down opposite the treasury, and watched the multitude putting moneye into the treasury. Many rich people put in large sums. And a poor widow came, and put in two copper coins, which make a penny.e And he called his disciples to him, and said to them, “Truly, I say to you, this poor widow has put in more than all those who are contributing to the treasury. For they all contributed out of their abundance; but she out of her poverty has put in everything she had, her whole living.”f

Mark 12.38-44, my translation

And in his teaching, he said: “Look out for those scribesa who desire to dress in gowns, handshakesb in the markets, the first rowc in assemblies,d and the first seatc at dinners—they eat up the households of widows and as a pretext pray long prayers; these will receive a greater verdict.”

Also, while seated across from the treasury, he saw how the crowd threw copperse into the treasury; many rich people gave much; and one beggar-widow came and threw in two farthings (which are a halfpennye). And having called his students together, he said to them, “Amen, I tell you that that widow, the beggar, threw in more than everyone who threw coppers into the treasury; for they all threw theirs in from what they had extra, but she threw hers in from her shortfall—her whole life.”f

Textual Notes

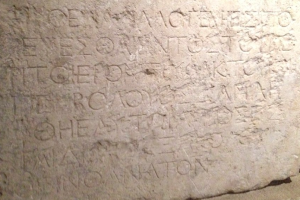

A stone bearing the Temple Warning (dating

probably to the first cent. BC or first CE1).

Photo by oncenawhile, used under a CC

BY-SA 3.0 license (source).

a. Beware of the scribes/Look out for those scribes: A hyper-literal translation of the Greek here would be “Beware from the scribes the ones desiring,” followed by the list of things these shady scribes like so much—all of which amount to public recognition of various kinds. (Their “long robes” or “gowns,” by the way, are their στολαῖς [stolais], the term from which we get stole.) In itself, this information is trivial, but it touches on a big difficulty in New Testament studies.

Now, I say what follows below reluctantly. I don’t like to believe a person or group is ignorant or foolish; I like throwing accusations of malice around even less, since sincere ignorance is at least an innocent problem. Unfortunately, most people would rather be thought of as smart bad people than stupid neutral ones (or stupid good ones, even). This can make it quite tricky to extend people the benefit of the doubt without also unnecessarily offending them.2

This case is a little simpler than usual, albeit in a way I don’t relish. I am not nearly so experienced a translator as the scholars who produced the RSV-CE: that makes it harder to believe this is a matter of mere ignorance. Moreover, the apparent fault I’m about to attribute to them—and I do make a point of the word “apparent”—is one that I believe every Christian should approach with delicacy. It is a fault of which Christians as a body have been exceedingly guilty throughout history, and one that makes us ridiculous as well as wicked. And, well, I gotta quit stalling at some point, so let’s discuss it.

Hey look, I can keep stalling just long enough

to offer you this kitten picture before we get

into it

I think the RSV’s rendering here shows an anti-Semitic bias: in other words, that it exhibits anti-Semitism not present in the text itself.3 To be clear, I’m not trying to get into the vexed question of whether the New Testament is anti-Semitic in general; that’s far too important and sensitive a subject to make it a secondary note in a blog post. Here, I’m discussing only this part of this Gospel.

I argue that, while an anti-Semitic reading of the English translation is natural, that reading is not in truth what the Greek text conveys. Let’s break that down into its two constituent parts—a) what the English suggests, and b) whether that’s there in the Greek—and handle them one at a time.

a) The way the RSV-CE presents Jesus’ words here makes it sound like the message is: Watch out for the scribes, and here is why they are bad. Here’s the problem with that. The scribes and the Pharisees are very closely related, both in the New Testament and in the popular Christian perception of the New Testament; and it is the Pharisees who are the ancestors of all rabbinic Judaism. They were also, as I never tire of reminding my readers, the theological “party” to which Jesus himself belonged. Those associations make a general, indiscriminate attack on the scribes seem a lot like a bigoted message against practicing Jews as such.

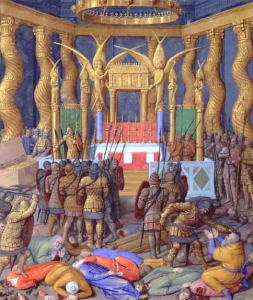

Pompey in the Temple of Jerusalem (15th c.),

by Jean Fouquet4

b) However, I don’t think the “Watch out for the scribes” version is the best translation in the first place. The syntax5 suggests that this is what’s called an attributive phrase—i.e., that the message is closer to Watch out for bad scribes (or the bad ones among the scribes), and here is what those look like. This makes more sense anyway, given the preceding context we got last week, in which a scribe’s nearness to the kingdom of heaven is highlighted. This changes the tenor of the text, from a warning about the scribes, as such, to a warning about (so to speak) bad eggs among the scribes. Besides that being a much more natural assumption to make about “scholars in general,” it is also one that can be cross-applied to similar classes and groups of leaders.

b. salutations/handshakes: Since the kiss is no longer a normal greeting in our society (and has in fact been restricted almost entirely to immediate family members and lovers—which historically speaking is extremely strange, but anyway), ἀσπασμοὺς [aspasmous] or “kisses” doesn’t have an ideal translation. On the basis of its role in our culture, I reluctantly went with “handshake.” “Embrace” might have been better—or maybe just biting the bullet and using “kiss” and just explaining it in the notes, since here I am doing that anyway.

Woodcut of kissing the feet of the Pope, from

Lucas Cranach the Elder’s Passionary of

Christ and Antichrist (ca. 1520-1550).

c. the best seats … and the places of honor/the first row … and the first seat: The “firsts” in my translation are parts of two compound words, πρωτοκαθεδρίας [prōtokathedrias] and πρωτοκλισίας [prōtoklisias]; both were “first” in the sense of prestige, not necessarily in the sense of being the first person to actually sit down.

d. synagogues/assemblies: The term synagogue comes from Greek (here συναγωγαῖς [sünagōgais]), meaning “gathering together” or “assembly,” and thus by extension a place at which assemblies were regularly held. The modern Hebrew term for “assembly” is כְּנֶסֶת [k’néséth], and thus a beth knesset is a synagogue in the modern sense. (I’m not sure how the English usage of the Greek-derived synagogue came to mean only Jewish congregations.)

Remains of a first-century synagogue at Gamla,

located in what are now the Golan Heights.

Photo by Hanay, used under a CC BY-SA 3.0

license (source).

However, some Sephardic and Romaniote6 Jews instead refer to synagogues with the word kal, which descends from the Classical Hebrew קָהָל [qâhâl]. This term referred to an Israelite assembly, such as petitioned Samuel to choose them a king; the Hebrew name of Ecclesiastes, קֹהֶלֶת [Qóhéléth], often translated “The Preacher,” is related. Its most convenient equivalent in Ancient Greek was arguably ἐκκλησία [ekklēsia], meaning “[those] called forth” or “summoned.” You may recognize as the root of many languages’ words for “church”: the Albanian kishë, French église, Irish eaglais, Italian chiesa, Spanish iglesia, Welsh eglwys, and more besides,7 not to mention the English surnames Eccles and Eccleston. And speaking of Ecclesiastes, Ἐκκλησιαστής [Ekklēsiastēs] is a Greek translation of קֹהֶלֶת, which stuck when the book was carried over from Greek into Latin.

e. money … copper coins … penny/coppers … farthings … halfpenny: The actual terms here are χαλκὸν [chalkon], λεπτὰ [lepta], and κοδράντης [kodrantēs]. Now, translating classical monies (based more or less on the classical drachma) into modern terms is kind of inevitably a pain in the neck. It’s not that there are no words you can use to do it; there are. (The drachma, to grossly oversimplify, was a day-laborer’s wage, which, based on the current minimum wage in the US, pins its worth at something between $50 and $60.) But the ways of translating the meanings of these coins in the text, as opposed to in a note, are all unsatisfying on multiple levels.

A drachma; the obverse shows the head of

Bacchus, the reverse a bunch of grapes. Photo

by the Classical Numismatic Group, Inc.,

used under a CC BY -SA 3.0 license (source).

Option 1: Convert everything into modern currency. In theory, this gives the reader the idea of how much “purchasing power” we’re dealing with. This runs into the issue of inflation as soon as your translation is more than three or four years old. However, my main problem with this really is that it would feel ridiculous. I can’t listen to “‘Show me the coin used for the tax,’ so they brought him a dollar” with a straight face, especially not when they go on to proclaim that Cæsar’s “image and inscription” are on it (butt out, Sacagawea, apparently this is Tiberius’s now).

It also renders the units of currency unrecognizable. The reason that matters is, sometimes the values or proportions of numbers, e.g. when used in parables, are symbolic. “Master, look: you left me with $136,140 dollars, and I have added another $136,140 dollars to them” being met with “Well done, good and faithful servant; have rule over five cities” does not make the obvious lesson that “five talents, and I have added five talents” does.

Option 2: Use the original currency names and units. This is certainly the most literal way of doing it (and here, as so often, I call into question my own real use of the “as literal as possible” rubric!). The problem with this is, no one nowadays knows what the hell a κοδράντης is, nor what to make of the fact that they’d have one if they could only put their hands on two λεπτὰ. It’s better than option 1, but it still isn’t very communicative.

Option 3: Keep the units, but render the currency into something more familiar. Like many English-language translators before me, I’ve settled on “vaguely old-timey Anglo money terminology,” which can suggest value without being absolute about it. There are still a lot of problems with this (it doesn’t give a very clear or specific notion of value; it feeds the slightly silly picture Americans tend to have of the Roman Empire speaking with a British accent, etc.), so that it isn’t much better than the question-mark option 2 leaves in the reader’s mind; however, I think its slight better-ness is worth having.

A lump of elemental copper. Photo by

Jonathan Zander, used under

a CC BY-SA 3.0 license (source).

For those who love pedantic details, though, here’s the skinny. The word χαλκὸν (with the dictionary form χαλκός [chalkos], if you need to look it up) literally means “copper” in Greek, and, as with pennies in Anglo-American culture, thus became a name for “small change.”

The second, λεπτὰ (dictionary form λεπτόν [lepton]), can be rendered “thin” or “small.” The lepton had already been the practical equivalent of the American penny for centuries: i.e., it was both the smallest denomination available, and one one-hundredth of the drachma.

Finally we have the κοδράντης, or, to give it its Latin name, the quadrans—and you can probably guess where the King James got the idea to equate this with a farthing, i.e. one-fourth of a penny. The quadrans was a bronze or brass coin so small, it didn’t even depict the emperor; four quadrantēs made one as, a coin typically struck in bronze or, later, copper; and an as was a tenth of a dēnārius, the Roman equivalent of the drachma.

Valentine of Milan Mourning Her Husband, the

Duke of Orléans (1802), by Fleury-François

Richard. (Valentine of Milan, a.k.a. Valentina

Visconti: 1389-1408.)

f. her poverty … whole living/her shortfall—her whole life: As in Luke, Jesus concludes his time in the Temple during Holy Week by focusing not on the piety of some eminent scholar of the Torah, but that of a penniless widow. The leading pastor at my last Protestant church pointed out once in a sermon on this passage that this widow could have used those lepta to buy food (not much, maybe, but a little)—and that therefore, by tithing them, she was choosing to give a fast to God as well.

I find that what takes me to pieces reading this text is the word ὑστερήσεως [hüsterēseōs]. It is ultimately derived from an adjective, ὕστερος [hüsteros], that means “latter, after, behind” (and often, by extension, “too late”). At first, I rendered “her shortfall” as “what she had for tomorrow”; when I reread the passage, I couldn’t recall what details moved me to do that, and double-checking my Greek dictionaries was unenlightening, so I decided to change it in the interest of accuracy, but that phrase does capture the concreteness of this woman’s plight, and, equally, of her decision to give away what little she had.

Footnotes

1I can’t know for sure, of course, but at a guess, I think I am one of the, mmm, eleven people who sincerely prefers “Common Era” to “anno Domini” on the pedantic grounds that the date doesn’t accurately record Christ’s birth.

2If your reaction to this is “… So?”, meaning either Why be so stringent about giving people the benefit of the doubt? or Why not just offend people and be okay with that?, these are not just personal tics; I consider them duties of charity. They may sound eccentric, but really, they’re just applications of the Golden Rule (which, if you actually think about it for a few minutes, is a terrifying standard of conduct). I don’t think any of us enjoy people assuming the worst about us; and, while plenty of us take pleasure in being offended, it’s a complex and (if we’re honest with ourselves) somewhat sick pleasure.

3This refers to a historical episode from two or three generations before Christ: in 63 BC, Pompey the Great (a Roman statesman and general who was Julius Cæsar’s principal rival) was invited to mediate a succession dispute in the Hasmonean kingdom of Judea. The situation deteriorated further; eventually Pompey besieged Jerusalem, took the city, and not only entered the Temple but went all the way into the Holy of Holies, defiling it. (The very next day, he ordered it to be ritually cleansed and that its services resume—which we may be sure the Jews would have done in any case.)

4Specifically, in this case, the placement of the definite article.

5Sephardic Jews are those whose religious culture was formed in Medieval al-Andalus, Portugal, and Spain; they are the second-largest single Jewish ethnicity, after Ashkenazic (Central European) Jews. Romaniotes are a small community of Greek-speaking Jews who have lived in Greece since before the New Testament was written. They got the name “Romaniote” because they lived in the Byzantine Empire, which referred to itself as the Roman Empire (later, Rhomania), and its inhabitants not as “Byzantines” but Romans. (Most of the Romaniotes were exterminated in the Holocaust; of the survivors, a majority emigrated either to Israel or the United States, but a few remain, principally in Athens and northern Greece.)

6The English word “church,” however, is not among them: it is a much-mutated form of another word, κυριακόν [küriakon], which means roughly “thing that belongs to the lord,” referring to the literal building. In late Ancient or early Byzantine Greek (around the 200-500 CE range), the most common pronunciation of κυριακόν became something like kir-ee-ah-kun; as an Arian form of the Christian faith began spreading among the Goths as early as the fourth century, κυριακόν became something like *kirikā. This in turn became the Anglo-Saxon ᚳᛁᚱᛁᚳᛖ [ċiriċe] (or ᚳᚣᚱᛁᚳᛖ [ċyriċe]), which slowly evolved into the modern “church.” Terms like the Croatian cȓkva, Finnish kirkko, German Kirche, Scots kirk, and Swedish kyrka are related.