This post has received minor edits—chiefly, the correction of the reference for the translated Gospel—as of 12 Nov. 2024.

Or: The Antepenult

I had not hitherto known that the song “The Final Countdown” was literally by Europe. Now, we both do. And, as of the end of this sentence, we will also both know that Europe is the name of a Swedish glam metal band (I assume this is where the continent got the name). This has nothing to do with the Gospel text we’re considering, and I did not have to bring it up, but still chose to do so.

Europe, photographed from above (I assume

this is also the band)1

Anyway, we are on our third-from-last text from Mark this year! This is why this is “the antepenult,” a term which in Greek grammar denotes the third-from-last syllable. The last syllable is the ultima; the one before it is the penult (the element pen- here is the same as in the word “penumbra”—it comes from the Latin pæne, “almost”). Therefore, the one before the penult is logically the ante-penult, as it is before (ante) the almost- (pen-) last (ultima[te]) syllable. The point is, you’re now armed with the meaning of “antepenult,” and you are welcome.

But to speak of less weighty things. In this post and the next, we are in Mark 12. (I thought at first of combining this Gospel passage with the next, but it turned out I had a lot to say about passages, even after trimming.) I am, alas, late with this post, which is on the Gospel reading from the third; I hope to get the post on tomorrow’s text out as soon as possible The very last reading from Mark, taken from chapter 13, will be read at Mass on the seventeenth. (The Gospel reading for the last Sunday of the liturgical year will come from John.)

But we are now in Mark 12. This passage falls during Holy Week, and contains some of the juicy banter the Synoptics record between Jesus and the Temple establishment. This was all primarily if not entirely on Monday and Tuesday, according to the chronology Mark furnishes us with.2

The Shema

The beginning of the Shema from a small scroll

designed for use in tefillin or a mezuzah. The

exaggerated letter at the upper left is the last

letter of echad, “one.”

The first segment of this passage (paralleled in Matthew 22, and partly also in Luke 10) relates the famous “greatest commandment.” At all our Masses in the Anglican Use, immediately before the Kyrie, the celebrant recites this prayer:

Hear what our Lord Jesus Christ saith: Thou shalt love the Lord thy God with all thy heart, and with all thy soul, and with all thy mind. This is the first and greatest commandment. And the second is like unto it: Thou shalt love thy neighbor as thyself. On these two commandments hang all the law and the prophets.

This is closer to the version of Jesus’ reply found in Matthew. Mark, interestingly, opens not with the commandment proper, but with the Shema (pronounced shem-ah). This prayer, which forms the basic “creed” of Judaism, is derived from Deuteronomy 6:4. The text is below, with an attempt at a character-to-character transliteration, varying slightly from my usual method. (Remember, this requires reading from right to left; I’ve also written the vowels out, Roman style, instead of trying to somehow imitate the vowel pointing.)

שְׁמַע יִשְׂרָאֵל יְהוָה אֱלֹהֵינוּ יְהוָה אֶחָֽד

ðâḥê’ —- uwnyeholê’ —- le’ârśiy ȝāmš

In left-to-right form, this is Sh’māȝ Yiš’râ’ēl, [TETRAGRAMMATON] ‘Elóhēynû, [TETRAGRAMMATON] ‘éḥâdh], which means,

“Hear, O Israel, the LORD our God, the LORD is one.”

(As is often the case going from Hebrew into English, there are alternative translations that lay the emphases slightly differently, e.g. “the LORD our God is the only LORD.”) Note that the very first imperative of the text, the command to hear, is in a sense a mitzvah3 unto itself. The Targum Onkelos, the authoritative Aramaic translation of the Torah (produced in the second century), apparently rendered the verb שְׁמַע as “accept.” On one level, then, this passage contains three commandments, even though they are one in substance.

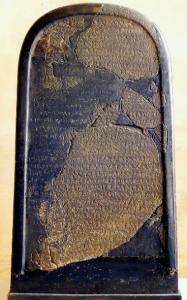

Remains of the Mesha Stele, a 9th-cent. BC

inscription with the oldest known instance of

the Tetragrammaton. Photo by Mbzt—CC BY

3.0 license (source).

Mark 12:28-37, RSV-CE

And one of the scribes came up and heard them disputing with one another, and seeing that he answered them well, asked him, “Which commandment is the first of all?” Jesus answered, “The first is, ‘Hear, O Israel: The Lord our God, the Lord is one; and you shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your mind, and with all your strength.’a The second is this, ‘You shall love your neighbor as yourself.’ There is no other commandment greater than these.” And the scribe said to him, “You are right, Teacher; you have truly said that he is one, and there is no other but he; and to love him with all the heart, and with all the understanding,b and with all the strength, and to love one’s neighbor as oneself, is much more than all whole burnt offeringsc and sacrifices.” And when Jesus saw that he answered wisely, he said to him, “You are not far from the kingdom of God.” And after that no one dared to ask him any question.

And as Jesus taught in the temple, he said,d “How can the scribes say that the Christ is the son of David? David himself, inspired by the Holy Spirit, declared,

The Lord said to my Lord,e

Sit at my right hand,

till I put thy enemies under thy feet.

David himself calls him Lord; so how is he his son?” And the great throng heard him gladly.

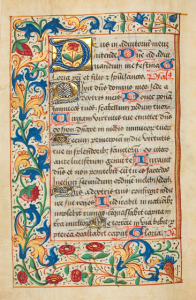

Page from the 14th- or 15th-cent. Psałterz

Florianski (“St. Florian’s Psalter”),

illuminator unknown.

Mark 12.28-37, my translation

And one of the scribes came up, who had heard them debating and seen that he replied well to them; he asked him, “Which is the first charge of all?” Jesus replied: “The first is: Hear, Israel, the Lord our God is one lord, and you will love the Lord your God with your whole heart and soul, your whole thought and strength. The second is: You will love your neighbor as yourself. Greater than these, there is no other charge.”a

And the scribe said to him, “Well said, teacher—of a truth you say that he is one and no other is greater than he; and to love him with one’s whole heart and intelligenceb and strength and to love one’s neighbor as oneself, it is more than all burnt offeringsc and sacrifices.” And Jesus, seeing that he replied thoughtfully, said to him: “You are not far from the kingship of God.” And nobody dared no more to question him.

And Jesus said in replyd while teaching in the Temple: “How do the scribes say that the Anointed is a son of David? David himself says in the Holy Spirit, The Lord said to my Lorde: ‘Sit at my right hand until I may place your enemies underneath your feet.’ David himself calls this person ‘Lord,’ so how is he his son?” And a great crowd listened to him delightedly.

Textual Notes

a. Jesus answered, “The first … greater than these”/Jesus replied: “The first … no other charge”: Jesus was not the first rabbi to be asked this question, nor the first to offer this type of answer. There’s a famous story about Hillel the Elder, an eminent rabbi who died while Jesus was a child4; he was once challenged by a scornful unbeliever, who said he would convert only if Hillel would teach him the whole Torah while he, the unbeliever, was standing on one foot. The rabbi accepted the challenge. When the unbeliever had assumed the requisite posture, Hillel said to him: “What is hateful to you, do not do to your neighbor. That is the whole Law; the rest is commentary—go and study.”

Talmudysci [“Talmud Readers”] (c. 1920-1940),

by Adolf Behrman

Now, many Christians may see immense significance in the fact that Hillel’s answer leaves out the explicitly God-centric commandment Jesus quotes. Alternatively or in addition, they may be grave and filled with many clicks of the tongue over how, unlike Jesus who uses the Golden Rule, Hillel uses the Silver.5 However, I doubt these differences mean much. Of the two major rabbinic schools that existed in Jesus’ day, Beyt Hillel and Beyt Shammai,6 Jesus—to the extent that he belongs to either—is mainly aligned with Beyt Hillel; part of the reason he so often clashes with fellow Pharisees may be that Beyt Shammai was in the ascendant at this time (and so it remained until around the year 70). This makes it, not impossible, but unlikely that this was intended as a critique of Beyt Hillel.

There is another reason too. The divisions we draw within the Torah—ceremonial versus moral versus civil precepts, or more broadly between its “horizontal” (man-to-man) and “vertical” (man-to-God) aspects—are valid as far as they go. However, they weren’t necessarily how ancient people thought about the Torah. St. James tells us that “whosoever shall keep the whole law, and yet offend in one point, he is guilty of all.” And of course St. Paul says:

He that loveth another hath fulfilled the law. For this, “Thou shalt not commit adultery,” “Thou shalt not kill,” “Thou shalt not steal,” “Thou shalt not bear false witness,” “Thou shalt not covet”; and if there be any other commandment, it is briefly comprehended in this saying, namely, “Thou shalt love thy neighbor as thyself.” Love worketh no ill to his neighbor: therefore love is the fulfilling of the law. —Romans 13.8b-10

All “second table,” love-of-neighbor stuff, with nary a word about the Lord thy God. What then? Is Paul then a purveyor of the anthropocentric woke social gospel? May it never be. But if we may thus show mercy to Paul, “then that same prayer doth teach us all to render / the deeds of mercy” to Hillel the Elder also, surely—or do we build again that which we have destroyed, and so prove ourselves transgressors?

b. understanding/intelligence: The word used here, συνέσεως [süneseōs], originates from the verb συνίημι [süniēmi], which has the primary meaning “to put together.” It soon took on the same metaphorical meaning as the English phrase, and could also mean things like “to perceive, hear, observe.”

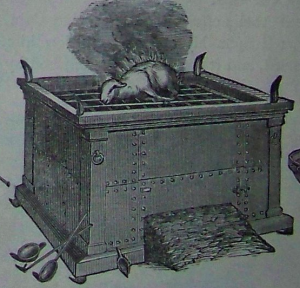

c. whole burnt offerings/burnt offerings: This refers to those offerings that were entirely burnt to ash. The Hebrew term is קָרְבַּן עוֹלָה [qâr’bān ȝôlâh], which means something like “ascending sacrifice,” the—metaphorical!7—idea being that the aroma of the offering “ascended to God’s nose” and placated his wrath, the same way the wicked are described as being a “stench” or “smoke” to him.8, 9

An artist’s rendering of the Altar of Burnt

Offering in the Court of the Priests,

immediately outside the Holy Place (from

the Holman Bible of 1890).

This distinction is drawn because most sacrifices were not wholly burnt. It was more normal, in all ancient religious practice—pagan as well as Judaic—to burn a relatively small portion of the sacrificial animal, primarily the fat, and cook the rest. The meat would then be split at least two ways, between the offerer and the priest. (Among Gentiles,10 meat left over after the offerer and priest had had their share—and there usually would be such extra meat, since common offerings included large animals like oxen and pigs—would be sold to the local public. This is how the whole “eating meat sacrificed to idols” issue emerged for the ancient Church.)

d. he said/Jesus said in reply: When I was a boy, I was a little irked that Jesus seems almost incapable of merely saying things in the Gospels, but must always “reply and say” or “answer and say.” To some extent, this is just a difference in habits between speakers of Ancient Greek and Modern English. However, if I’m not mistaken, this sort of reduplication (a device known as pleonasm) is more common in the documents of the New Testament than it would be in an average selection of Ancient Greek texts. If indeed I am not mistaken about that, it’s possible that this reflects the form in which these early rabbinic battles of wits took place. To this day, Judaic discourse is known for relying extensively on rhetorical and riddling questions, and for highly esteeming those who can find their way out of a seemingly hopeless intellectual trap by finding the reply that was, as it were poetically, unimpeachable—which might well be a counter-question, as in Mark 11:30. (This is why, in the episode early in Luke when Jesus is lost in Jerusalem and eventually found “talking shop” in the Temple, even though it says that he was “hearing them and asking questions,” the things that amazed the scholars then present were “his understanding and answers.”)

An early 16th-cent. illumination of Psalm 110

e. Lord: This is not an unusual word, in either the New Testament or the Septuagint; on the contrary, κύριος [kürios] or “lord” is very common, partly because this word was usually used in place of the Tetragrammaton whenever it appeared in the Tanakh. This is borrowed from the Hebrew and Aramaic custom of replacing the Tetragrammaton with Adonai, “my lord” (Elohim “God” and ha-Shem “the Name” were, and are, also used as substitutes). Several cultures have naming taboos of similar kinds, typically applying to divinities, rulers, or the dead.11

Psalm 110, which Jesus is quoting here, exhibits one of the effects such substitutions can have—for of course if the elected substitute occurs “naturally,” so to speak, in close proximity to an occasion on which it is being inserted, one must either duplicate the word or choose a different substitute word for this instance. The echo-like sound of “The LORD said to my Lord” is quite noticeable; and this is not its sole or greatest oddity.

Psalm 110 is widely agreed to be among the oldest in the Psalter. It contains one of the Bible’s vanishingly few allusions to Melchizedek, in verse 4. Traditional Judaic commentary makes it a hymn of, or about, Abraham coming to the aid of Lot (see Genesis 14.14-20); maybe this “priesthood in the order of Melchizedek” is reflected in Abraham’s intercession for Sodom in ch. 18 (the fact his appeal was ultimately refused doesn’t mean it wasn’t intercessory).

Melchizedek (1681) by Michael Willmann.

Photographed by Fallaner, used under

a CC BY-SA 4.0 license (source).

The traditional Christian interpretation, on the other hand, is Trinitarian; the LORD and Lord are understood to be the Father and the Son respectively. Psalm 110 is one of the most-quoted psalms in ancient Christian texts, and reciting it is specially associated with several festal observances: monastics who follow the Rule of St. Benedict recite Psalm 110 every Sunday, and the Book of Common Prayer (one of the principal sources for the Anglican Use liturgy) assigns it as one of the psalms recited at Evensong on Christmas, besides recurring monthly like every other psalm.

Footnotes

1Oh, fine, kill the joke: this is actually the (justly famous) Hereford Mappa Mundi or “world chart,” created around the year 1300 and preserved in Hereford Cathedral in the west of England. Like many Medieval maps, it takes the form of a “T-O” map, dividing the round world (enclosed in an O) into the three unequal continents of Africa, Asia, and Europe (distinguished from each other by an internal T, with east rather than north at the top). The thing in the middle that looks kind of like an upside-down soccer cleat is the Mediterranean Sea; the British Isles are squeezed in at the lower left part of the circle.

2Mark’s account of Holy Week begins with chapter 11 of his Gospel, with Maundy Thursday beginning at 14:12. If we understand the Triumphal Entry (11:1-11) as having taken place on Palm Sunday, then the curse of the fig tree and the cleansing of the Temple (11:12-19) took place on Monday, the latter followed by a certain amount of teaching. The following morning, Tuesday, the fig tree is found to be withered (11:20-26), and the bulk of the confrontations with the Pharisees and clergy take place (11:27-12:44), concluding with the Olivet Discourse (ch. 13).

3The word mitzvah is a direct borrowing of the Hebrew מִצְוָה [mits’wâh], “commandment,” used of the 613 specific commandments contained in the Torah. (The plural is mitzvot, accented on the second syllable.)

4Hillel the Elder died in the year 10 CE or thereabouts. It is unprovable—I can’t even really say that there’s evidence for it, only that it is strictly possible; nonetheless, I am tickled by the possibility that Hillel the Elder may have been one of the scholars in the Temple among whom SS. Mary and Joseph found Jesus when he had been lost in Jerusalem.

5If you haven’t run into this distinction before, the Golden Rule is Do unto others as you would have them do unto you, while the Silver Rule is the negative form—Do not do to others what you would not have them do unto you.

6We’ve touched on these before now, but as a refresher: a beyt or beth (בֵּית in Hebrew—literally “house”) was a rabbinic school. Loosely speaking, Beyt Hillel and Beyt Shammai were the generous and rigorist schools of interpreting the Torah in the first century.

7That is, all Jews and Christians are historically known to have believed this was a metaphor since well before the first century CE. Whether the ancient Israelites already thought this in the pre-Exilic period, I don’t know, although my guess based on the Book of Psalms would be that they did. However, I think it’s also perfectly possible that—to borrow a leaf from C. S. Lewis (I know, so unlike me)—the pre-Exilic Israelites did not think it was metaphorical not because they thought it was literal, but because they did not think about the question at all.

8There are many Hebrew idioms that get translated into English literally about zero percent of the time. This conception of how sacrifices work may, however, be related to one such idiom: in many of the Bible verses that tell us God is “slow to anger” or some similar phrase (e.g. Psalm 103:8), what the text literally says is that God is “long of nose”!

9Formerly, the term used for these sacrifices in English—and which you may still find, primarily in older literature—was “holocaust” (from a Greek phrase meaning “wholly burnt”). I imagine no explanation is needed for why using that term is now widely regarded as, to say the least, distasteful in discussions of sacrifices to the God of Israel.

10I’m not sure whether the same was true of Jewish practice while the Temple stood. I would assume not, since, unlike the pagan priesthoods of Rome or Greece (which I gather were often elected positions), the Jewish priesthood consisted in the whole tribe of Levi, and there would always be plenty more Levites to distribute sacrificial meat to. However, this is only a guess on my part.

11In Japan, for example, deceased emperors receive posthumous names: the monarch who presided over the country during World War II is now known in Japan as the Shōwa Emperor, and never referred to by the name he bore in life.