The Hallowmas Gospel

This past Sunday, we heard blind Bartimæus healed by Jesus; on Friday, we hear in the second reading that “when he appears, we shall be like him, for we shall see him as he is“—our vision of Christ, our knowledge of him, is transformative. Now we come to the solemnity’s Gospel.

A little ironically, the second reading for this solemnity is as much or more keyed into the Gospel passage than the first was—ironically, because the first is from Revelation (a literal vision!). It is one of the most famous and preached-on passages in all the Gospels, the beginning of the Sermon on the Mount, a set of benedictions named after a Latin term for them: the Beatitudes. Grammatical variance between my rendering and the RSV’s is just about nil, but there are several vocabulary items I did pick out for examination.

The beginning of Matthew in the Book of Kells

A How-To Manual for Being a Christian

Vocabulary aside, I have some more general remarks to make about the Beatitudes. Most of them can be found after the textual notes, but I wanted to say a little bit about the Sermon on the Mount (Matthew 5-7) up front here.

The Sermon on the Mount was taken by Christians of the first several centuries as our ethical handbook. There’s plenty more in the New Testament—the Sermon on the Mount wasn’t touted as if it superseded other material—but Matthew was rather a favorite among the Gospels, and the Sermon on the Mount comes early on in it. Moreover, it touches on a lot of the recurring themes of Jesus’ preaching, such as non-retaliation, kindness not only to strangers but even to enemies, and putting heart-level obedience before ritual conformity; at the same time, it introduces us to some of the key marks of Jesus’ style, including prominent use of parables and paradoxes, and a conspicuous lack of reference to other rabbis.

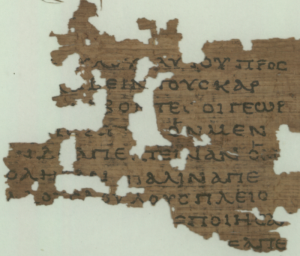

Papyrus 104, a fragment of a copy of the

Gospel of Matthew dating to the mid-second

century; it is about two by three inches in

size, and has parts of Matt. 21:34-37.

It seemed to me as though, ten to twenty years ago, the Sermon on the Mount was receiving a new attention from American Christians. The wars our country had become involved in during the Bush administration (to speak of nothing else) appeared to be prompting serious reflection about the link between evangelical faith and Republican politics, at least in the minds of some. This was happening at around the same time that a revived interest in the history of the Church seemed to be taking hold. Even solid evangelicals were reading about—and even directly reading the works of!—people like St. Benedict, St. Francis, and St. Thomas à Kempis; topics like the nature (and number!) of the sacraments or the propriety of praying for the dead, while not fashionable exactly, were at least discussable.

Maybe the idea that that was a general reality was my own wishful thinking, and it really wasn’t like that outside the circles I knew or was in touch with. Or maybe the current the current climate is, at least in part, a backlash against the self-examination involved. Either way, I certainly don’t feel like I see that kind of interest in the Sermon on the Mount now, nor the reflectiveness, the readiness to ask ourselves if we’ve been or done wrong. Least of all do the recent crop of severely online Deus Vult avatars and Orthobros seem to have patience for any actual teaching of Jesus; I hope it just looks like that from the outside, and that I’m judging them unfairly.

But, as I said, I’ll come back to this. Let’s dig into the text.

The Beatitudes Sermon (ca. 1890), James Tissot

Matthew 5.1-12a, b, RSV-CE

Seeing the crowds, he went up on the mountain, and when he sat down his disciples came to him. And he opened his mouth and taught them, saying:

“Blesseda are the poorb in spirit, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.c

“Blessed are those who mourn, for they shall be comforted.

“Blessed are the meek,d for they shall inherit the earth.

“Blessed are those who hunger and thirst for righteousness,e for they shall be satisfied.f

“Blessed are the merciful, for they shall obtain mercy.g

“Blessed are the pure in heart, for they shall see God.

“Blessed are the peacemakers, for they shall be called sons of God.

“Blessed are those who are persecuted for righteousness’ sake, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.

“Blessed are you when men revile you and persecute you and utter all kinds of evil against you falselyh on my account. Rejoice and be glad, for your reward is great in heaven, for so men persecuted the prophets who were before you.”

Matthew 5.1-12a, b, my translation

Looking at the crowds, he went up the mountain; and when he had seated himself, his students came near him, and opening his mouth, he taught them, saying:

“Blesseda are beggarsb in spirit, because theirs is the kingship of the heavens.c

“Blessed are mourners, because they will be consoled.

“Blessed are the gentle,d because they will inherit the land.

“Blessed are those who hunger and thirst for justice,e because they will be full-fed.f

“Blessed are the compassionate, because they will receive compassion.g

“Blessed are the clean in heart, because they will see God.

“Blessed are peacemakers, because they will be called God’s sons.

“Blessed are those who are persecuted for the sake of their justice, because theirs is the kingship of the heavens.

“You are blessed whenever they reproach you and persecute you and say every evil thing about you, the liars,h for my sake. Be joyful and delighted, because your recompense is much in the heavens; for in the same way, they persecuted the prophets who were before you.”

The beginning of Matthew in the Lindisfarne

Gospels (probably created about a century

earlier than the Book of Kells)

Textual Notes

a. Blessed: Some modern translations have tried replacing “blessed” with “happy.” In my opinion, this really doesn’t work. Being happy isn’t at all the same thing as being blessed; a blessing is something bestowed upon you by someone else—that idea is nowhere in the word “happy,” emotionally speaking. And intellectually, it’s even worse, because “happy” is related to the words “happen” and “happenstance.” In etymological terms, it’s specifically not a gift!

The word “happy” also has—again, personal opinion—none of the gravitas that many instances of the word “blessed” in Scripture call for. The cacophonous effect of “happy” is at its worst in the Psalms. It would be nearly as bad in the Beatitudes; however, I note with pleasure that the NABRE (the version used for the Mass readings in most Catholic parishes in the US) does use “blessed.”

b. poor/beggars: The difference here is plainly small, and “poor in spirit” is more euphonious, so at first this might seem like me being different for the sake of it. However, if we leave æsthetics to the side, I think (if I do say so) that “beggars” is a better translation, because it zeroes in more closely on the meaning that’s relevant to the text. “Poor” has several meanings: It defaults to the fiscal, but it can cover broader sorts of badness (“poor quality”), especially a lack of desirable fullness or variety (as when I tell people my Spanish is poor). Poverty of spirit does not have an instantaneously obvious significance. What is richness of spirit? Virtue? The grace of God? Is this a blessing on people who are … un-blessed?

“Which seems recursive—and also impossible.”

(Quote from 6:12-14 at the link; image

provided for under fair use.)

“Beggar,” on the other hand, focuses our attention on the point of poverty of spirit: conscious, acknowledged dependence. This is not something most of us much relish. The exceptions are, as a rule, the saints.

c. heaven/the heavens: The distinction here may not matter! Then as now, the plural meant much the same thing as the singular. Moreover, Matthew’s “kingdom of heaven” may be a pious euphemism for “kingdom of God”1; Mark uniformly uses the latter, and if his greater tendency to record the Aramaic Jesus used is anything to go by, he is the more pedantic of the two when it comes to knowing what Jesus said word-for-word.

On the other hand, it’s possible Jesus used both phrases. Perhaps thanks to the influence of Hekhalot literature, there seems to have been a slightly more developed notion of the multiple tiers in which heaven was supposed to consist (hence St. Paul’s allusion to being “caught up to the third heaven,” which he plainly expects his readers to understand or at least take in stride). If Jesus did use “kingdom of the heavens” as well as “kingdom of God,” and did specifically say “the heavens” rather than “heaven,” he may have meant something particular by the plural—though I admit, I can’t even begin to guess what.

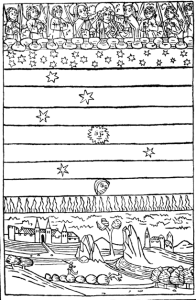

A 15th-cent. depiction of the Seven Heavens

d. meek/gentle: The word “meek” has become a bad translation of the Greek πραΰς [pra’üs]. It isn’t that it contradicts the text; it doesn’t, not quite; but the meaning has changed into something irrelevant to it.

As far as I can tell, “meek” in normal English means something like “the ‘shrinking violet’ type.” Now, I have a lot of that type in myself (like St. Paul, my posts are weighty and powerful, but my presence is weak and my speech contemptible), and am also naturally lazy. So I might be expected to perk up at this idea. But “shrinking violet” isn’t what πραΰς means—it’s just that it’s close enough to tempt a translator to go with the traditional phrase.

Blossoms of the Viola cazorlensis (a species

that apparently has no common name, but

is in the genus Viola, i.e. violets)

What πραΰς does mean is “mild” or “gentle.” And gentleness, which you’ll recall is a fruit of the Spirit,2 is a concept that I believe we misunderstand quite consistently and seriously in our culture. We tend to think of it as a virtue of the weak—even, maybe, as the weak making a virtue of necessity.

This is not true. Counterintuitively, gentleness goes very naturally with strength. Weakness generally has something to prove. Strength, on the other hand, if it wants to avoid breaking things or injuring people, has to make a point of softening itself, of observing limits. “A bruised reed he will not break …”

A Kālacakra mandala from Tibet, part of

the inspiration for the idea and name of

the Wheel of Time in the eponymous series

by Robert Jordan.

This was impressed on me in The Eye of the World, the first Wheel of Time book. The book opens with three Young Male Protagonists (and a few others) who Secretly Have Great Power, hailing from a Small Village of Nobodies, etc. etc. One of the three is the village blacksmith, Perrin. The narrator notes that Perrin has not only been exceptionally big and strong since he was fairly young, but realized it. As a result, he tends to move slowly and handle things gently, because he wants to avoid hurting people. This is a great method of characterization; more importantly, it’s a great reminder of what strength really means: The stronger you are, the more effortlessly you accomplish tasks that require strength. Noise and bombast are sure signs of weakness.

Having said that, I hasten to add, noise and bombast aren’t necessarily signs of weakness in the thing the noisy person is making noise about. Sometimes people try to meet their desires less directly. We’ve all heard that guy at the gym who encourages himself out loud when he deadlifts—you know, he wears one of those giant belts, drinks from a gallon container instead of a water bottle? To be fair, maybe he only does the annoying “C’mon, c’mon, RRRRR, c’mon, YOU gottit” thing because he habitually talks to himself out loud. But if he is doing it for attention, then he’s revealing a ravenous appetite for affirmation, from total strangers no less. That’s a dangerous weakness, 100%. It just doesn’t happen to be a physical weakness.

I bet justice could judge stuff a lot

better if she took off that blindfold

e. righteousness/justice: This represents a word that is oddly tough to translate in a satisfying way. The word is δικαιοσύνη [dikaiosünē]. It’s derived from δίκη [dikē], meaning “right,” “law,” or “justice” (in the abstract, not as a quality of a person’s character); the adjective “just, right, lawful” is δίκαιος [dikaios], and the suffix -σύνη is a bit like the English –ness in its function. Therefore, δικαιοσύνη is the character trait that prompts people to behave justly or lawfully.

The thing is, we rarely talk about “justice” as a quality that people have nowadays; it sounds very old-fashioned and formal to call somebody “a just man.” As for “righteous,” that either sounds like specifically religious lingo, which δικαιοσύνη was not, or else like skater bro talk, and skater bros had not yet been invented.3 Probably the closest equivalent we have would be “integrity”? “Honesty” might do as well. But neither of them are all that close, especially because neither one connects to the idea of law that is present in δικαιοσύνη. (Also, while “honest” is fine, I’ve coincidentally been wondering for months what the adjectival form of “integrity” is, and come up with nothing but “integrated.”)

f. satisfied/full-fed: The verb here is a more vivid one than “satisfied”—”stuffed” is more the idea. It’s also used in the accounts of the feeding of the five thousand, to describe how they felt after they finished the loaves and fish.

g. merciful … shall obtain mercy/compassionate … will receive compassion: “Mercy” is another one of those ideas that isn’t difficult to understand, but which we don’t seem to talk much about in modern times, at least not under that name. You’ll occasionally hear about “compassion,” though I feel as if I heard a lot more about that virtue when I was young. You’ll also hear, now and then, about pity—basically always as a bad, contemptible thing, given out of scorn and rejected with justified outrage by its targets.

There is no doubt pity of that kind exists. (I once dubbed it “compassion-coaggression” after passive-aggressiveness.) It’s one of the besetting vices of a certain type of Christian, or of Christians in a certain mode.4 However, the fact that this has become the dominant if not exclusive meaning of “pity” strikes me as a dark sign, and not an isolated one.

We lived in a capitalist, militarist, high-imprisonment world power already twenty years ago. Still, phrases like “compassionate conservatism” were slogans back then. Even if the slogan was hypocritical, the fact that appeal was even made is significant.

Today, if I may trust my own experience, the partisans of the Right and Left alike are increasingly merciless, and increasingly frank about it. Increasingly sadistic, even. I won’t pretend to think both sides are equally guilty in this regard. The Right seems far more brazen in its inhumanity to me than the Left does, and the Left’s inhumanity also seems more leavened with other things. However, we do not improve by focusing on other people’s sins; besides which, the Left’s tendency to eat its own, even over trivial infractions, is infamous for a reason. More importantly, if I’m right in perceiving a general rise in distrust and harshness and resentment (or “polarization” if you prefer journalese), that’s a bad thing for everybody, regardless of their political convictions. And it’s bad in a way Christians should be specially concerned with, because mercy is supposed to be one of the main masts of our ship.

“What a pity that Bilbo did not stab that vile

creature, when he had a chance!”

“Pity? It was pity that stayed his hand.”

—The Lord of the Rings, Book I, ch. 25

Admittedly, “Blessed are the merciful” isn’t the Beatitude that hooks into the “vision” theme of the other two texts in this series. Nevertheless, this may be the Beatitude that American Christians need to meditate on and pray to obtain more urgently than any other.

h. falsely/the liars: As so often, Greek has offered us a participle we don’t want (we have participles at home), so there’s a good chance it’ll come out as something else in English. We also run into a minor point about syntax, which almost never affects translation.

Greek is an inflected language, i.e., several of its parts of speech take different forms depending on their role in the sentence.6 One consequence of having inflected nouns is that, unlike English, you can juggle the word order of a sentence almost as much as you want without the meaning getting confused. Moreover, inflected verbs mean you don’t technically need a subject, since at least a pronoun’s-worth of information will be attached to the verb anyway. There’s still a typical word order—Greek does usually put the subject first, for example. But if you want some variety, or to emphasize something, or to make a joke, etc., you can move the words around a lot to do it.

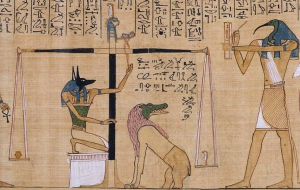

The “weighing of the heart” depicted in an

Egyptian scroll (13th c. BC): Anubis (left)

weighs; Thoth (right) records; the monster

Ammit (center) devours deceitful hearts.

The word at stake in all this is ψευδόμενοι [pseudomenoi], a participle which means “lying.” Its form shows that it applies to the subject of the clause “whenever they reproach you … for my sake.” However, it actually appears almost at the end of the sentence, giving it a rhetorical flourish (this subject-last placement is allowed, but it’s very unusual). The subject of that clause is therefore something like “they, lying.” But the “they” isn’t stated (because it doesn’t have to be), and as mentioned, “lying” is kept back at first. This means the translator has to decide among three options:

a) render it very literally as “lying,” which (because English is so word-order dependent) requires moving it to the front and so losing the effect of the delayed subject;

b) change it into an English adverb, i.e. “falsely,” like the RSV does; or

c) split the difference and treat it like a substantive adjective.7

I decided on option c): It’s a hair more literal than option b), while still allowing the original rhetorical structure to be preserved.

The Calumny of Apelles (1495), by Sandro

Botticelli. Apelles was a painter from

Classical Antiquity, whose own allegorical

painting “Calumny” is lost.8

A Different “Eightfold Path”9

Now then, to return to the subject of the Beatitudes in general.

The Beatitudes form a strong opening for the Sermon on the Mount—a set of pithy, striking sayings that all have the same format of “Blessed are [group of people], for [future].” They’re ideal for memorization. More than that, they follow an internal logic. Let’s start with the front halves. The sequence of whom Jesus blesses is:

- beggars in spirit

- mourners

- the gentle

- those who hunger and thirst for justice

- the compassionate

- the clean in heart

- peacemakers

- those who are persecuted for the sake of their justice

Note how the first, third, fifth, and seventh are what we might colloquially call “soft” virtues like gentleness and mercy, while the second, fourth, sixth, and eighth are “hard” virtues like penitence and purity. With this mutual interweaving in mind, we’re in a better position to appreciate the sequence: it’s simultaneously a zig-zag (soft and hard virtues alternating) and a straight line (each virtue building on the previous)—which, when you come to think of it, is the shape of a staircase, one of the most ancient and traditional ways of going up.

Stairs from the Opéra Garnier in Paris. Photo

by Manfred Heyde, used under a CC BY-SA

4.0 license (source).

We’ve just dealt with the zig-zag; the straight line lies in how each of the Beatitudes builds on the previous. Beggars in spirit implies an embrace of our total dependence on God. Mourners has long been associated with repentance for sin—a natural thing for one who is thus consciously relying on God to do. Someone who has experienced this kind of beggary and mourning might thereafter be especially sensitive to the pain they involve, and therefore specially careful to be gentle; as the remembered shame that tends to go with repentance fades, they are also likely increasingly to want to live up to the standard they fell short of, which we might poetically call a hunger and thirst for justice. This allows the gentleness they had to become something bolder and more robust, an active compassion. Meanwhile, perseverance in the attempt to become just, especially together with the compassion for others that (if it’s doing it’s job) drives out hypocrisy, will result in being clean in heart. All these virtues together make for someone with both the desire to see their neighbors reconciled to one another, and the skills of humble, patient understanding that help them really to become peacemakers.

Well, people who behave like that are not convenient for a certain kind of leader (or aspiring leader), religious and secular alike. A leader whose power thrives on conflict—perhaps he views himself as “too manly” for all that “beggary and gentleness” stuff, or he may claim (sincerely or not) that some enemy is out to get us all, so there’s no time for the delays that “penitence and justice” stuff requires—that leader will be sure to persecute peacemakers. We’ve thus passed through all eight Beatitudes.

St. Simon of Cyrene depicted in the Church of

St. Pierre in Limours, a town outside Paris.

Photo by G. Freihalter, used under a CC

BY-SA 3.0 license (source).

Okay. So what?

The Narrow Gate

For heathen heart that puts her trust

In reeking tube and iron shard,

All valiant dust that builds on dust,

And guarding calls not thee to guard

For frantic boast and foolish word,

Thy mercy on thy people, Lord!

That is the closing stanza of the poem “Recessional,” written by, of all people, Rudyard Kipling. Yes, the original “white man’s burden” guy. Make no mistake, his ideology was seriously screwed up, but there are signs—like this poem—that he was more than a blind jingoist. He needed to do a lot more than he in fact did, but he was capable of reflection and self-critique, and he did sincerely do some.

Okay; so extra what? Well, it seems to me as though American churches—and maybe it’s a broader problem than America, but I’m sticking to what I know about—could learn something from Rudyard Kipling. (No, they don’t need to learn the “white man’s burden” thing, we have been there and done that.) American churches seem to me as though they are becoming downright allergic to reflection and self-critique. My own belief is that this is one of several bad fruits of the culture war, but whether I’m right about that or not, it is an exceedingly bad symptom.

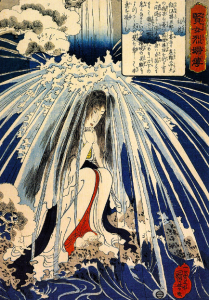

Hatsuhana doing penance for her husband under

a waterfall10 (ca. 1842), woodblock print by

Utagawa Kuniyoshi, one of the last masters of

the ukiyo-e or “floating world” style.

Repentance, humility, admission of fault—these things are the beginning of Christian ethics. They’re the first lesson. A hazy grasp of them, or worse, an indignant rejection of them, are surer signs of de-Christianization than any number of lewd jokes or four-letter words. And it seems an awful lot like “indignant rejection” of the Christian precepts of humility, forgiveness, and being forgiven are not just commonplace among non-Christians in this country. I actually get the impression that such indignation against the ethics of the Sermon on the Mount, if anything, more common among Christians, and above all, high-profile converts. How are new, adult converts being served that poorly by the people catechizing them?

Footnotes

1It may seem puzzling to use a euphemism rather than say “kingdom of God.” What’s there to euphemize? The short answer is, “God.” The name of God, a.k.a. the Tetragrammaton, was treated with extreme care by Jews; even words approaching it would be employed with reverence, and sometimes omitted (whether in speech or writing) in favor of more distant allusions. The same practice has left plenty of traces on the English language: phrases like “thank heaven” or “oh my goodness” did not emerge at random.

2And yes, it’s the same Greek term. Or rather, it’s the noun derived from the same adjective (πραΰτης [praütēs]).

3Skateboards, however, had arguably been around for millennia, if we choose to regard them as heavily modified members of the chariot family.

4The mode is well-illustrated in this passage from The Name of the Rose (Fifth Day, Terce, p. 353), describing a speech given to two delegations of monks and clergy by the novel’s leading character, Br. William: “… Legislation over the things of this earth … has nothing to do with the custody and administration of the divine word, an unalienable privilege of the ecclesiastical hierarchy. Unhappy indeed, William said, are the infidels, who have no similar authority to interpret for them the divine word (and all felt sorry for the infidels).”

5The speakers are of course Frodo and Gandalf. For any who don’t recognize it, the picture of Gollum used here comes from the 1977 Rankin-Bass adaptation of The Hobbit, which was my own first exposure to Tolkien. The film is an odd mixture of bad and good; YouTuber Jess of the Shire has a pretty good review of it on her channel, which exhibits its gorgeous animation (including its unique designs for Elrond, Gollum, the Orcs, and the spiders of Mirkwood), as well as its (mostly) top-tier music.

6Anglo-Saxon was an inflected language, nearly as much so as Latin. Modern English has a little bit of inflection left, mostly in its pronouns, like the different forms who-whose-whom or they-theirs-them. The possessive -‘s on nouns is also a relic of inflection, as are a handful of verb endings, -ing being an example..

7A substantive adjective is an adjective that plays the role of a noun. This is more common in inflected languages like Latin, but it’s not unknown in English; think of expressions like “the Reds” to denote Communists.

8From left to right, the figures in the painting are as follows: i) Truth, the sole nude figure, her eyes heavenward; ii) in black, looking back toward Truth, Repentance; iii) in red and yellow, Perfidy, i.e. conspiracy; iv) being dragged along the ground, the victim, sometimes mistakenly called “Apelles”; v) in white and blue (colors normally associated with virtue), dragging the victim, Calumny, i.e. slander; v) Fraud, mostly hidden behind Calumny while she arranges the latter’s hair; vii) leading the accusers, and the only male of the group besides the victim, Rancor, i.e. envy; viii) to the king’s right, not looking at the accusers, Ignorance whispers into one of his ears; ix) the king himself, whose eyes are also downcast, and who has ass’s ears like the foolish Midas; x) Suspicion, clad in green, who alone is looking toward the accusers as she whispers in the king’s other ear.

9Normally, the “Eightfold Path” is an allusion to Buddhist ethics, symbolized by the eight spokes of the wheel of Dharma.

10Hatsuhana was the wife of Iinuma Katsugoro, a sixteenth-century Japanese samurai. According to the story behind this particular woodblock print, when Iinuma was taken ill, Hatsuhana did penance for a hundred days under a waterfall, beseeching a kami to spare his life; her prayer was granted after her death.