The Light of the Eyes

A tetramorph, an interpretation of

the cherubim based on the “four living

creatures” in Revelation 4.

I didn’t have much to say about the Gospel for October 27th. Accordingly, when I looked and found out they all have a motif in common, I decided to combine it with the epistle and Gospel for All Saints. Except then this post got so long, I needed to split it back into three (because absolutely nothing goes as you expect, ever). But they are three connected posts: one on the Gospel for next Sunday; one on the epistle for the Solemnity of All Saints; and finally one on the Gospel for the Solemnity. The motif in question is sight.

In the Gospel text for next Sunday, sight is what Bartimæus asks for from Jesus, and when he has received it, he immediately follows him to Jerusalem. Part of the reason I didn’t have much to say about this is, the lesson could hardly be less subtle!

Passing to the epistle (a.k.a. the second reading) for All Saints—or, as we call it in the Anglican Use, Hallowmas—”See” is the very first word. Nor is this mere coincidence; as we’ll be getting to, this links it with the most prominent symbolism of the Johannine writings.

Thirdly, as a bit of foreshadowing for Part II, the Gospel for that same festival is the Beatitudes, which include the declaration that “the pure in heart … will see God.” We don’t notice it as readily as first-century Jews might have, but this is a pretty dramatic promise in a culture whose foundational religious text states in no uncertain terms that

Thou canst not see my face: for there shall no man see me, and live. … I will put thee in a cleft of the rock, and will cover thee with my hand while I pass by: and I will take away mine hand, and thou shalt see my back parts: but my face shall not be seen. —Exodus 33.20, 22-23

(A little ironically, the first reading for Hallowmas comes from Revelation, which is literally an account of a vision, yet is the only one of these four not to have a strongly-themed allusion to sight.)

The Beatific Vision

Sight is a key idea throughout the Gospel of John and his first epistle, tying naturally into the recurring Johannine symbol of light, which represents both moral goodness and intellectual knowledge. At the same time, it’s a strongly material symbol. This is also extremely well-suited to John, the Gospel of the Incarnation par excellence. The briefer opening of I John is closely aligned with that of the Gospel:

That which was from the beginning, which we have heard, which we have seen with our eyes, which we have looked upon, and our hands have handled, of the Word of life; (for the life was manifested, and we have seen it, and bear witness, and shew unto you that eternal life, which was with the Father, and was manifested unto us;) that which we have seen and heard declare we unto you, that ye also may have fellowship with us: and truly our fellowship is with the Father, and with his Son Jesus Christ. And these things write we unto you, that your joy may be full. —I John 1.1-4

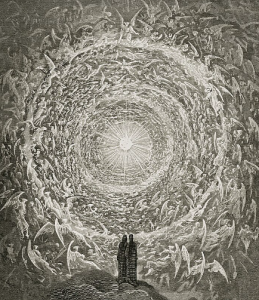

This is the foundation of the doctrine of the Beatific Vision: that the blessed in heaven, humans and angels alike, behold God face to face.

Oldest known (6th-cent.) ikon of Christ

Pantokrator preserved at the Monastery of

St. Catherine on Mount Sinai, one of the

only ikons to survive the Iconoclasms.

The doctrine is, of course, metaphorical. The only literal face God has is that of Jesus, and the point of the doctrine is not that literally looking at that face—as many of his enemies did, even when his exaltation had begun, on the Cross—confers blessedness, but that our knowledge of God in that state will be as simple and clear as seeing and speaking with a friend, a lover, or a father.

Then again, the word metaphor, in its Greek origins, means “something that light shines through.” If there’s any passage from C. S. Lewis that I cannot forget (and there are many), it’s one from the middle of Perelandra, the second book of the Cosmic Trilogy.1 It sets forth a picture of the Beatific Vision indirectly, in the character of its opposite—what, in Screwtape, he refers to as “the Miserific Vision”; and it is more literal about the idea than one might expect.

A Hideous Thing in the Third Heaven

The hero of the book, an Oxford scholar named Ransom, has been sent to the planet Venus (called “Perelandra” in Old Solar, originally the language of all hnau2 in the Field of Arbol3) to aid the inhabitants. They are about to experience a spiritual attack, one of the same kind as was made against our planet in time immemorial, recounted in the form of a myth in Genesis 3. He discovers after arriving that the attack is to be made through a fellow human being—a corrupt scholar named Weston, whom he has tangled with before. It soon turns out that, now, Weston is not merely corrupt; in a sickening scene, Ransom witnesses him become demon-possessed. A couple of chapters later, he discovers Weston (or at least, Weston’s body) in the midst of torturing the local wildlife.

First-edition cover of the novel (1943)

Note: C. S. Lewis was a very good writer, and even this abridged version of his description of what he later terms “the Un-man” is, in my opinion, some of the most effective horror writing in the English language. If you are prone to nightmares, you might want to skip this part: if you do, you can pick up again after the next picture, which is Francisco Goya’s The Adoration of the Name of God.

He saw a man who was certainly not ill … a man who was certainly Weston, to judge from his height and build and coloring and features. In that sense he was quite recognizable. But the terror was that he was also unrecognizable. He did not look like a sick man: but he looked very like a dead one. The face … had that terrible power which the face of a corpse sometimes has of simply rebuffing every conceivable human attitude one can adopt towards it. … And now, … thrusting aside every mental habit and every longing not to believe, came the conviction that this, in fact, was not a man: that Weston’s body was kept, walking and undecaying, in Perelandra by some wholly different kind of life …

It looked at Ransom in silence and at last began to smile. We have all often spoken—Ransom himself had often spoken—of a devilish smile. Now he realized that he had never taken the words seriously. The smile was not bitter, nor raging, nor, in an ordinary sense, sinister … It did not defy goodness, it ignored it to the point of annihilation. …

The stillness and the smiling lasted for perhaps two whole minutes: certainly not less. … Then there was a moment of darkness filled with a noise of roaring express trains. After that the golden sky and colored waves returned and he knew he was alone and recovering from a faint. As he lay there … it came into his mind that in certain old philosophers and poets he had read that the mere sight of the devils was one of the greatest among the torments of Hell. It had seemed to him till now merely a quaint fancy. And yet (as he now saw) even the children know better: no child would have any difficulty in understanding that there might be a face the mere beholding of which was final calamity. … As there is one Face above all worlds merely to see which is irrevocable joy, so at the bottom of all worlds that face is waiting whose sight alone is the misery from which none who beholds it can recover. And though there seemed to be … a thousand roads by which a man could walk through the world, there was not a single one which did not lead sooner or later either to the Beatific or the Miserific Vision. He himself had, of course, seen only a mask or faint adumbration of it; even so, he was not quite sure that he would live.

—Perelandra, ch. 9

El Adoración del Nombre de Dios [The Adoration

of the Name of God] (1772), by Francisco Goya,

located in the Cathedral-Basilica of Our Lady of

the Pillar in Zaragoza, Spain.

Corrections

Having (I hope!) partly gotten our imaginations around the concept of the Beatific Vision thanks to Jack “the C. S. is for Csi-fi” Lewis, I must immediately add two provisos about that passage.

One (which Lewis himself knew perfectly well) is that, strictly speaking, the concept of the Miserific Vision as something really equivalent to the Beatific is nonsense. For an “antigod” to confer on all who see its face an agony of the same absolute kind as the blessing conferred on those who see God, it would need to attain a “perfect evil” that matched God’s perfect good. But any being that attempted this would cease to exist, long before achieving it, because being, just as such, is good; there can be no “ideal badness” as there can be ideal goodness. The implied metaphysics of ranking the Miserific Vision (if it exists) alongside the Beatific are a lot like thinking that, when we get to heaven, we’ll be able to tell God the Father apart from God the Son because the Father has a white beard instead of a brown one.

The other proviso is more of a course correction than an intellectual correction. Think back. What was the point of dipping into Perelandra and reading about this “Miserific Vision” business in the first place? The Goya painting above, besides being something of a palate cleanser, is also intended as a reminder. “There is one Face above all worlds merely to see which is irrevocable joy”. The same motif hovers behind every page of Till We Have Faces; and both The Voyage of the Dawn Treader and The Last Battle hint at it in their closing chapters too.

Now, let us turn to our first Gospel text of this series.

Mark 10.46-52, RSV-CE

Christus Bartimæus (1861), by Johann Heinrich

Stöver; photo by Marion Halft, used under a

CC BY-SA 3.0 license (source).

And they came to Jerichoa; and as he was leaving Jericho with his disciples and a great multitude, Bartimæus,b a blind beggar, the son of Timæus, was sitting by the roadside. And when he heard that it was Jesus of Nazareth, he began to cry out and say, “Jesus, Son of David,c have mercy on me!” And many rebuked him, telling him to be silent; but he cried out all the more, “Son of David, have mercy on me!” And Jesus stopped and said, “Call him.” And they called the blind man, saying to him, “Take heart; rise, he is calling you.” And throwing off his mantle he sprang up and came to Jesus. And Jesus said to him, “What do you want me to do for you?” And the blind man said to him, “Master,d let me receive my sight.” And Jesus said to him, “Go your way; your faith has made you well.” And immediately he received his sight and followed him on the way.

Mark 10.46-52, my translation

And they came into Jericho.a And while he was going out from Jericho with his students and enough of a crowd, the son of Timæus, bar-Timæus,b a blind beggar, was sitting by the road. And hearing that Jesus the Nazarene was there, he began to shout and say, “Son of David,c Jesus, take pity on me.” And many people rated at him to be quiet; but he shouted so much the more, “Son of David, take pity on me.” Stopping, Jesus said: “Call him.”

And they called, saying to the blind man, “Cheer up, get up, he is calling you.” So he threw his cloak aside, leapt up, and came to Jesus. And replying, Jesus said to him: “What do you want me to do?”

The blind man told him, “Rabboni,d that I may see again.” And Jesus told him, “Go; your faith has healed you.” And right away he saw, and followed him on the road.

Textual Notes

The Tower of Jericho (ca. 8000 BC), excavated

at Tel es-Sultan, near the Ein es-Sultan camp

in east-central Palestine. Photo by

Salamandra123—CC BY-SA 3.0 license (source).

a. Jericho: This doesn’t affect the passage particularly, but as a neat fun fact, Jericho is a serious contender for the title of oldest still-inhabited city in the world. In the early 2000s, evidence was also discovered there that agriculture may be thousands of years more ancient than previously thought. Hitherto, the fig was thought to have been domesticated in about 4500 BC. However, in a house in Jericho dating to around 9400 BC (so, contemporary with Göbekli Tepe), the remains of figs were found which came from a variety of fig that can’t be pollinated by insects—it’s perpetuated only through cuttings, meaning it requires human maintenance to survive. This is only about three hundred years after the beginning of the present Holocene geological epoch,4 which began with the end of the last ice age.

b. Bartimæus/bar-Timæus: This name could come from טָמֵא [ṭâmē’], “unclean”; the symbolic force of the “son of uncleanness” being cured by Jesus is, again, fairly blatant!

However, “son of uncleanness” also doesn’t sound like the sort of name a person would give their child. On the other hand, Timæus (or more strictly, Τίμαιος [Timaios]) was an actual Greek name, related to Timothy—both are derived from τιμή [timē], “honor.” Timæus straightforwardly means “honorable, honored,” while Timothy is a little ambiguous: it can mean either “honored by God” or “gives honor to God.” (Aramaic was the native language spoken by most Jews in the area at the time; however, some Jews, even in Palestine, were native speakers of Greek, and it wasn’t unknown to give children Greek names, as those of SS. Andrew and Philip attest. For a parallel, not every American whose mother-tongue is English sticks to Anglo-Saxon names for their children, or even broadly European ones.)

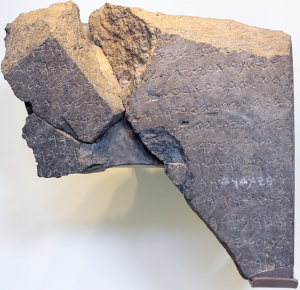

c. Son of David: It’s possible—though I’m not clear how likely it is—that Bartimæus’s use of this title is significant. The reason why has to do with the Judaic theology of the Messiah. That theology is not at all interchangeable with the general Christian outlook on the subject, so a brief overview is in order.

The Tel Dan stele (9th-cent. BC), featuring

the oldest known reference to the House

of David, in paleo-Hebrew. Photo by Oren

Rozen— CC BY-SA 4.0 license (source).

Christianity, as we know, believes in a single messiah, preceded by Elijah—not literally Elijah, but one who, like Elisha, comes “in the spirit and power of Elijah.” We interpret these figures as being Jesus Christ and St. John the Baptist (the latter of whom used to play a larger role in Christian devotion5). Judaism traditionally expects four distinct messianic figures: אֵלִיָּהוּ [‘Ēliyâhū], or Elijah; the מָשִׁיחַ בֵּן יוֹסֵף [Mâshîāḥ bên Yósêf], or the Messiah ben Joseph; the מָשִׁיחַ בֵּן דָּוִד [Mâshîāḥ bên Dâwidh], or the Messiah ben David; and the צָדוֹק הַכֹּהֵן [Tzâdhóqh hā-Kóhēn], or the Righteous Priest.

This is based on the vision recorded in Zechariah 1:18-21, which describes four “carpenters” or “artisans” who will cast out the “four horns” that have scattered Israel. Who or what these “four horns” are is not made clear there. Horns are a conventional symbol of strength, and frequently stand for nations or national rulers. They could indicate empires that ruled the Jews, either directly (say, the Babylonians, Egyptians, Medes, and Persians6), or in more of a “four points of the compass” sense.

Now, I don’t fully understand all four of these figures and their role in Judaic theology. However, I gather that the following more or less holds:

- Elijah’s role, much as in Christian theology, is to herald the others. (I have the impression that it’s more ambiguous whether this will literally be the person of Elijah in Judaism.)

- The Messiah ben Joseph helps rebuild the Temple, and dies in battle against the foes of Israel. (There seems to be some dispute or uncertainty about whether the Messiah ben Joseph will surely come, or if his coming is in some way determined by circumstance.)

- The Messiah ben David restores the Davidic monarchy and reigns in peace and prosperity over Israel; during his reign, the rest of the world recognizes the God of Israel as the one true God, the dead are resurrected, and God creates a new heaven and earth.7

- The Righteous Priest is the part I understand least. I assume he is the restored high-priestly counterpart to the restored monarchy’s Messiah ben David. However, I haven’t been able to find much about him (in an admittedly cursory search).8

The prophet Zechariah as depicted

by James Tissot, ca. 1900

Accordingly, Bartimæus could be identifying Jesus as specifically the Messiah ben David, as contrasted with one of the others. This would presumably be connected with his evident confidence in Jesus’ power to heal him.

But there are two connected reasons I phrase this tentatively. One is that I’m not clear on when this fourfold-messiah doctrine became more or less the norm in Judaic theology. It could have arisen basically any time after Zechariah’s career (around the return from the Exile, in the late fifth to early fourth centuries BC), I suppose; but it doesn’t follow that this doctrine was standard in Jesus’ day, or even that it existed (messianism in general did, but that’s not quite the same). I suspect it was around in the first century, because of my other reason for tentativeness: the contemporary theological diversity of Judaism. The theologies of the Essenes and Pharisees would be places to look for messianic speculation; I’m not clear whether Sadducee theology even had a messianic dimension, and as for the Zealots, while they certainly had an interest in messianism, they weren’t particularly focused on theology.

d. Master/Rabboni: To my surprise, the information I found about this term’s origins was rather confused. The Hebrew I understood to underlie it was רַבּוֹנִי [rābônî], which I had always read meant “my master,” or occasionally “our master”—more with the idea of teacher than of owner or commander, but with a similar polysemy to the English word “master.” Confusingly, however, I kept finding forms that had rib- where I expected rab-, and wasn’t entirely sure what to do with them; they matched up with the Yiddish form rebbe well enough, but Yiddish developed much later (beginning ca. the 10th century), half a continent away; I couldn’t tell if these rib- forms were a related term, or an alternate form of the same term, or a chance mis-transcription, or what.9

Beatrice and Dante gazing into God in

heaven: illustration (1850) for Paradiso

Canto 31, by Gustave Doré.

After some digging (and I’m sure I still missed quite a lot!), I was able to find two forms that might underlie rabboni. One was the Hebrew רַבֵּינוּ [rābēynū], which uses the suffix ־ֵנוּ [-ēnū], “our” (it also appears in the name Immanuel), thus meaning precisely “our teacher.” The other, and the most promising of the bunch, was the Aramaic רַבָּן [rābân], with the same meaning as the Hebrew. If at any point רַבָּן had become something of a courtesy title, perhaps coming to suggest “great teacher” despite its origins, then it would have been simplicity itself to tack the suffix -i “my” on the end, producing an Aramaic word that any Greek-speaker would probably transcribe ῥαββονί [rhabboni].

Part II to come!

Footnotes

1Which, as I shall never tire of saying, is its proper title: “the Cosmic Trilogy.” Cosmic, not “Space”! Lewis devotes practically a whole chapter of Out of the Silent Planet to explaining why “space” is the wrong word, and our ancestors rightly said “the heavens.” But something tells me that “the Heavenly Trilogy” would be a bridge too far for you people, so we’re settling for “Cosmic.”

2Hnau is the word for “rational animals” in the Cosmic Trilogy. It embraces at least six species: the hrossa, pfifltriggi, and séroni of Mars; human beings on Earth, or Thulcandra, “the silent planet”; the unnamed species—possibly humanoid, but we are given no details—that inhabits our Moon; and the also-unnamed humanoid species that inhabits Perelandra. (It would be a convenient word to adopt into English, if only to facilitate discussions of, e.g., whether corvids, dogs, dolphins, elephants, or gorillas are hnau, or may be approaching that status.)

3The Field of Arbol is the solar system (Arbol being the Old Solar name for the sun). Only its inner worlds appear to be intended for habitation, and only four of those five are confirmed to be inhabited: Mars (Malacandra in Old Solar), the Moon (Sulva), the Earth, and Venus. Nothing is said of whether Mercury (Viritrilbia) hosts, or is meant one day to host, intelligent life. Additionally, hnau on Malacandra long antedate humanity, and indeed their time drawing to a close before much longer—at least, “before much longer” in terms of the geologic timescale; on the other hand, the hnau of Perelandra had only just arisen at the time of our Second World War. (We are not told where in the sequence the hnau of Sulva belong, but, based chiefly on the advanced corruption of their society alluded to in That Hideous Strength, my guess would be that they’re younger than those of Malacandra but older than us Earthlings, if only by a few million years.) The worlds outside the asteroid belt—for which we know the names Glund or Glundandra for Jupiter, Lurga for Saturn, and I think Neruval for Uranus—have some significance, hinted at in both Silent Planet and That Hideous Strength, but this is not elaborated.

4Not all geologists agree that we are still in the Holocene. Due to the increasingly extreme impact human beings have been having on the planet’s climate for the last century and a half (possibly longer, but planet-wide records only go back to 1880, meaning we have to infer temperatures by other means for earlier years), some scientists regard us as inhabiting a new geologic epoch, termed the Anthropocene. (On the geologic time scale, epochs normally last a few hundred thousand years; since this classification would mean the Holocene lasted only eleven thousand years, this may give the reader an idea why so many scientists are freaking out about climate change!)

5For instance, when we hear “St. John” without further specification today, we’re likeliest to think of the apostle; in the Middle Ages, an unspecified “St. John” would be at least as likely, if not more, to be the Baptist. I have a pet theory about the decline in St. John the Baptist’s devotional importance, according to which it is connected with the decay in our grasp of the appropriate distinctions between the spheres of law and grace, reason and revelation, and the political and ecclesiastical; but that must wait for another time.

6I’ve left the Assyrians out here, despite their being responsible for the loss of the ten (-ish) northern tribes, because Assyria had ceased to be even a local power centuries before Zechariah lived. Accordingly, I assume they would not be under consideration in a text like this one. However, I haven’t verified this by reference to any Jewish commentaries on Zechariah (or Christian ones, actually), so I’m not sure.

7Incidentally, this is why some (not all) Orthodox Jews sternly disapprove of the state of Israel, some even considering it a form of sacrilege. In their view, until and unless God restores the Jews to the land of Israel by the agency of the Messiah ben David, they are not meant to return there: at least, not en masse, with political intent. Besides being interesting to students of religion, this is an informative example of how and why the state of Israel’s claim to represent and act on behalf of the interests of all Jews is not necessarily credible—an important fact to bear in mind, when trying to navigate the sometimes-delicate problem of identifying anti-Semitism in the political sphere (it’s not at all as simple as “opposing Israel is anti-Semitic”).

8If only to show I’m not a total stick-in-the-mud, I won’t forbid Christian readers to be pleasantly intrigued that the three non-Elijah figures in this setup are a priest, a “son of David,” and a “son of Joseph.”

9This difference in vowels wasn’t a huge deal, because Semitic languages base words on what are called radicals. Radicals are sets of consonants, usually three, that encode a general concept: e.g., if the radical K-T-B encodes the idea “writing,” then inserting one set of vowels could produce the word katab “book,” while a prefix and another set of vowels make lektob “to write,” and a different prefix and set of vowels gives you maktab “school,” etc. The reason I was so puzzled was just that I hadn’t specifically come across the rib- forms before, and therefore wasn’t sure whether to consider the difference significant. There are a few other puzzles like this in New Testament Aramaic; the original word or phrase behind the nickname Boanerges, “sons of thunder,” is a famous example.