Again With the Competitiveness

This post’s passage is the Gospel text for October 20th this year. Having recently taught the disciples about the badness of rivalry and envy,,, Jesus almost immediately has to teach them the exact same thing again.

It’d be nice if we could look down on the Twelve for this. However, if we’re frank with and about ourselves, the Twelve probably learned faster than most of us. So let’s jump in, and we can all feel quietly embarrassed together!

Mark 10.32-45, RSV-CE

And they were on the road, going up to Jerusalem, and Jesus was walking ahead of them; and they were amazed, and those who followed were afraid. And taking the twelve again, he began to tell them what was to happen to him, saying, “Behold, we are going up to Jerusalem; and the Son of man will be delivered to the chief priests and the scribes, and they will condemn him to death, and deliver him to the Gentiles; and they will mock him, and spit upon him, and scourge him, and kill him; and after three days he will rise.”

The Ardagh Chalice, discovered in 1868 in

County Limerick, Ireland. Photographed

by Wikimedia contributor Sailko, used

under a CC BY-SA 3.0 license (source).

And James and John, the sons of Zebedee, came forward to him, and said to him, “Teacher, we want you to do for us whatever we ask of you.” And he said to them, “What do you want me to do for you?” And they said to him, “Grant us to sit, one at your right hand and one at your left, in your glory.” But Jesus said to them, “You do not know what you are asking. Are you able to drink the cup that I drink, or to be baptized with the baptism with which I am baptized?” And they said to him, “We are able.” And Jesus said to them, “The cup that I drink you will drink; and with the baptism with which I am baptized, you will be baptized; but to sit at my right hand or at my left is not mine to grant, but it is for those for whom it has been prepared.” And when the ten heard it, they began to be indignant at James and John. And Jesus called them to him and said to them, “You know that those who are supposed to rule over the Gentiles lord it over them, and their great men exercise authority over them. But it shall not be so among you; but whoever would be great among you must be your servant, and whoever would be first among you must be slave of all. For the Son of man also came not to be served but to serve, and to give his life as a ransom for many.”

Mark 10.32-45, my translation

They were on the road, going up to Jerusalem, and Jesus was ahead of them, and they were astonished, and fearful while following him. And he took the twelve aside again, and began to tell them the things which were about to happen—”Look, we are going up to Jerusalem, and the Son of Man will be handed over to the high priesrs and scribes, and they will condemn him to death and hand him over to the nations and they will mock him and spit on him and flog and kill him, and after three days he will rise.”

And coming forward to him, Jacob and John, the sons of Zebadiah say to him: “Teacher, we desire that whatever we will ask, you will do for us.” So he said to them, “What do you want me to do?”

They told him, “Grant us that one may sit on your right and one on your left in your glory.” Jesus told them, “You do not know what you are asking; can you drink the cup that I drink, or be immersed in the immersion that I am immersed in?”

They told him, “We can.” Jesus told them: “The cup that I drink, you will drink, and the immersion that I am immersed in, you will be immersed in, yet to sit on my right and port-side is not mine to give, but is for those for whom it is prepared.”

The scallop is a symbol of St. James the

Greater. From the Church of the Good

Shepherd, Rosemont, PA, by Francis

Helminski—CC BY-SA 4.0 license (source).

And when the ten heard, they began to get indignant about Jacob and John. But calling them together, Jesus said to them: “You know that those who seem to rule the nations lord it over them, and their great ones wield authority over them. It is not so among you; but whoever wants to become great among you, he will be your servant, and whoever wants to be first, he will be the slave of everyone; for the Son of Man too did not come to be served, but to serve, and to give his life in ransom for many.”

Textual Notes

a. amazed, and … afraid/astonished, and fearful: This seems to be picking up from last week’s passage about the rich young ruler, which included what was, back then, the counterintuitive and even baffling statement that the rich could enter the kingdom of heaven as easily as a camel could get through the eye of a (literal) needle.

A 19th cent. depiction of a camel in

a ceremonial procession, its rider

playing the drums

Most Christian authors and lecturers I’ve read or heard mention at this juncture that wealth was considered a sign of God’s favor under the Mosaic Covenant, and that this was what made this implicit woe to the rich so unexpected to Jesus’ disciples; if so, it apparently left them shaken thereafter. However, this involves us in a bit of a difficulty which I didn’t get into in my last, because that “if so” in the preceding sentence was a load-bearing phrase.

Let’s call the idea that wealth is a sign of God’s favor “the ‘naive’ view.” There are promises in the Torah that amount to divine blessings on virtue and curses on vice, but this proves less than it may seem to, since one of the things virtue means is “that which promotes human flourishing,” and vice, the reverse. When I thought about it, I realized that I don’t know whether Jewish sources substantiate the “naive” view, and the natural presumption to make would seem to be the other way: there were plenty of passages in the Tanakh that—one would think—would at least nuance things a bit. Job is the most cryingly obvious, but something similar can be said about much of Kings, Jeremiah, and several of the Psalms. Even for those who do not accept them as Scripture, II Maccabees and the Wisdom of Solomon both rebuke the “naive” view.

Now, according to surviving sources, the “naive” view did prevail among the Sadducees, so it’s not like it would have been pointless to rebut it. But the common people were generally much more influenced by the Pharisees, and I’d at least expect them to oppose the Sadducees on this point. Unfortunately, my other responsibilities this month mean I’m kind of running low on research time, so I’ll have to leave this as a question-mark for now, and hopefully revisit it another time.

St. John and the Poisoned Cup (1614), El Greco.

According to legend, someone tried to poison

John later in life, but when he blessed the cup,

the poison became a snake and slithered out.

b. James and John, the sons of Zebedee/Jacob and John, the sons of Zebadiah: Technically, we’ve dealt with these minor naming differences before, but as it’s been a minute, let’s review. We got the name James out of the Hebrew יַעֲקֹב [Yā3aqov]. It happened like this: Ya’aqov became the Greek Ἰάκωβος [Iakōbos], which became the Latin Iacomus, which became Old French James (pronounced zhah-mess), and thence, the English James. His father’s name started out in Hebrew as זְבַדְיָה [Z’vādhyâh], which went into Greek as Ζεβεδαῖος [Zebedaios]; the Latinized form was Zebedæus, and, English usually drops the –us ending from Latin names and turns æ into e or ee; thus, Zebedee. Jacob and Zebadiah are thus fully Anglicized, but a little bit closer to the Hebraic forms.

c. we want you to do for us whatever we ask of you/we desire that whatever we will ask, you will do for us: It’s easy to read this and be bowled over by the gargantuan ego implied in this request; however, a couple of ameliorating factors should be considered. One is a detail we learn from the parallel in Matthew: namely, that their mother was the one to actually make this request, not the disciples themselves. Then again, judging from Mark, it was their idea, suggesting they asked her to ask on their behalf—maybe this doesn’t make it better.

Zebedee, Salome, and the infants James and

John (1509) on the right panel of a triptych

altarpiece by Lucas Cranach the Elder

The other, however, definitely does, and might even suggest that we have something to learn from this bold-as-brass request. Jesus teaches his disciples about prayer in a few different places in the Gospels (e.g. Matthew 6-7 and Luke 11), and one of his persistent themes is that we should ask for what we want—and, bafflingly, that he will give us “whatever you ask in my name“. (I tend to think C. S. Lewis was correct in speculating that this probably refers to requests made in a state of holiness very few of us have ever approached; but it must be said, that is an interpretation, not what the text says.)

d. to be baptized with the baptism with which I am baptized/be immersed in the immersion I am immersed in: This appears to link up with the Pauline language that equates baptism with death; similarly, throughout the Bible, a cup is a common symbol of judgment. Psalm 75.8 is an excellent example: “in the hand of the LORD there is a cup, and the wine is red; it is full of mixture; and poureth out of the same: but the dregs thereof, all the wicked of the earth shall wring them out, and drink them.” (This is why the set of seven devices in Revelation 15-16 that are mostly described in English as “vials” or “bowls” are, in a few translations, rendered “cups” or “chalices.”1)

The Giving of the Seven Bowls of Wrath (c.

1531), by Matthias Gerung, apparently on

quite a pleasant day otherwise

How cups came to have this meaning, I’m not sure. One possibility that comes to mind is that, since executions in some places (e.g. Athens) were performed by administering poisons, the cup might have become a symbol of the death penalty by extension, and then spread to judgment generally. The obvious objection to that is, the Tanakh is a Hebrew document, not a Greek one, and the traditional method of execution in Hebrew society was by stoning—though a symbol does travel more easily than a change in legal custom.

e. be indignant/get indignant: This happens to be the same verb Mark used, several paragraphs ago, to describe Jesus’ reaction when he noticed that the disciples were not letting people bring small children to him.

f. servant … slave: The words in question are διάκονος [diakonos] and δοῦλος [doulos]; the latter term merits some discussion. That discussion ballooned far further out than just a textual note; it’s the rest of this post, actually.

Two Vital Disclaimers

As a preface to that discussion, none of the following means that any form of slavery is okay. It is, in fact, not! But there are cultural distinctions at play here worth understanding, because of how they can help us understand the New Testament.

Also, I am going to be using the word “slave” throughout the rest of this note, not “enslaved person” or some similar phrase. To be clear, the reason those phrases were created was a very good one: namely, the desire to accent these people’s human dignity and not their legal status. However, I don’t generally use the phrase “enslaved person,” etc., because I’m of the opinion that using it does not really achieve the desired effect.

I’m less sure of why that is. My guess is that it’s mainly because, whenever you read, write, or say it, a hallucinatory banner that reads “This phrase comes to you courtesy of Human Resources” briefly appears, and people really hate that. Furthermore (and while I’d entertain argument on the subject), I’m skeptical that any replacement term could make this discussion nicer if it were still comprehensible—euphemism treadmill and all that. And, thirdly, I am pretty firmly of the opinion that thus softening the hideousness of slavery is a ghastly error even when done with good intentions; and not everybody who gives vile institutions softened names does intend to do good.

Now then.

Slavery in Early Modern America

In the US, our idea of slavery is naturally dominated by our own nation’s history with racially-determined chattel slavery. The institution was far older than this justification for it, but the justification that came to be accepted was that Black people were inherently inferior to Europeans. Also in the interest of slavery, Blackness was eventually (and in theory still is) defined by the “one-drop rule.” Accordingly, American slavery was a racist institution and cannot be understood outside that ideological context; nor can American social, economic, military, religious, or political history in general be clearly understood, if slavery or racism (or their mutual entanglement) are minimized.

The Gemma Augustea (c. 10-30 CE), a low

relief made from a piece of onyx; on the

left, the lower tier shows two Gauls (sitting),

representing prisoners to be sold as slaves.

This was not at all how slavery worked or how it was thought of in antiquity. Now, some of the differences between the two systems—while they probably mattered quite a bit to slaves—were in principle only matters of degree. For example, punishments weren’t necessarily as habitually brutal in ancient Italy or Syria as they were in nineteenth-century Alabama or Maryland. In, of all periods, the reign of Nero, legislation was even passed that allowed slaves to bring legal charges against masters for mistreatment, while in the US it took a serial killer for some people to take the concept of “mistreating slaves” seriously. Manumission was also more normal in ancient societies than in the early Modern era; and, to a limited extent, some slaves could reasonably hope to save up enough money out of their wages (yes, really) to buy their freedom. Still, do bear in mind, we are talking about a society where the Roman paterfamilias had the power of life and death not only over his slaves, but over his children (and not just any children he happened to conceive with his slaves).

However, classical slavery really was a profoundly different institution from modern slavery at the conceptual level. Again—not to be repetitive, but because we live in a society and all that: it was still a morally wrong institution, because there is no okay way of viewing or treating human beings as property. But the differences between the older form and the more recent one affect how we understand what Scripture is telling us, and are therefore worth grasping.

Slavery in Classical Antiquity

To begin with, there was no concept of race back then.2 They had an idea of ethnicity, sure, and there was plenty of chauvinism on ethnic grounds: Greeks looking down on “barbarians” (i.e. all non-Greeks), for instance. But ethnicity was quite a different idea, defined principally by culture and language. The notion that Goths and Greeks were both part of a single “race” because they had similar skin tones, or that Greeks were more closely related to Goths than to, say, Egyptians for the same reason (despite the fact that Greek culture was far more like Egyptian culture than Gothic), would probably have struck them as ridiculous, and also as pointless.

Moreover, while the “one-drop rule” mentioned above is standard in our deeply silly racial taxonomy, integrating people from one ethnicity into another was not uncommon. It was especially characteristic of Roman society: the liberality with which they integrated peoples into their system is part of why the Empire lasted so long.3 Several great champions of Roman history were of “barbarous” extraction—and not just late imperial figures like Stilicho the Vandal, either: Cato the Elder (the one who closed all his speeches with his further opinion that Carthage must be destroyed) is reported to have had “reddish” hair, perhaps what we call strawberry blonde, which could presumably only have come from Gaulish ancestry.

It would be an overstatement to say nobody in Rome cared if your grandfather had been a foreigner; there are snobbish weirdos who latch onto that sort of thing in every age. But, importantly, caring about that was not given political importance. Rome even allowed freedmen to become citizens. (Plenty of people cared if your grandfather had been a freedman; this highlights one of the ways class, not race, was far more central to ancient societies.)

The Reasons for Enslavement

The rationale of ancient slavery was also different—or rather, rationales. There were several.

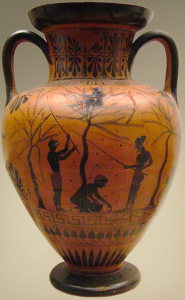

Slaves harvesting olives on an Attic4

amphora from the late 6th cent. BC

- Hereditary slaves. Some slaves were born into slavery, but this was because class status was normally hereditary, not because there was an ethnicity destined for it.5

- Criminal slaves. Crimes of some kinds could be punished with enslavement. Creditors enslaving their debtors was particularly common—conceptually, it was a way of forcing them to work off their debt; however, this caused sufficient unrest that citizens were made legally immune to debt-slavery in Rome in 313 BC.

- Captive slaves. Prisoners of war, unless they were particularly important people (and therefore either likely to be ransomed or liable to execution), were often sold as slaves; speaking of Carthage, its people were thus sold after the Third Punic War.6

- Destitute slaves. Impoverished families might sell one or more of their children into slavery, especially if the master they were being sold to was well-off, or would teach the child a trade. The truly desperate, if able-bodied, might even sell themselves into slavery, though for obvious reasons this was a rarity.

- Traded slaves. Slaves might have been bought from someone who bought them from someone who, etc., and come from who-knows-where. That probably meant one of two things: either that they just happened to have changed hands a great many times, and belonged to one of the aforesaid four classes; or, that they had been kidnapped, and either taken somewhere far from their land of origin so they could be sold without alerting people who knew them, or sold by people who did know them to someone who would take them far away. (This is part of why the Torah prescribes the death penalty for kidnapping.)

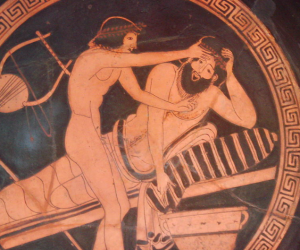

Ajax the Lesser taking Cassandra captive

during the sack of Troy, depicted inside

a fifth-cent. BC Athenian kylix (a typical

drinking cup)

Different Ideas About Slaves …

Incidentally, these causes are why the classical stereotype of the “servile character” was so different from the stereotype of slaves that prevailed in the American South. Both stereotypes were self-serving: they existed principally to reinforce the slave system, cherry-picking actual experiences with slaves according to their psychological usefulness. But they existed in different social contexts, and played on different tropes to make slavers morally comfortable with what they were doing.

The nineteenth-century stereotype was that Black people were naturally friendly, pliable, lazy, and dimwitted, and therefore both needed the direction of masters and were apt to accept it. This dovetailed neatly with the racial hierarchy theory that had lately become fashionable. (Note how this not only meant that any smart or “uppity” slave was behaving unnaturally, but so was one who was for some reason angry or resentful about being physically brutalized or otherwise treated as literal property.) The ancient stereotype of slaves was extremely different. C. S. Lewis explains it thus:

By a “servile” man we mean, I take it, an abject, submissive man who cringes and flatters. … [T]his was not the ancient idea of the typical slave … The true servile character [in classical sources] is cheeky, shrewd, cunning, up to every trick, always with an eye to the main chance, determined “to look after number one.” … Absence of disinterestedness, lack of generosity, is the hall-mark of the servile. The typical slave always has an axe to grind. … The slick waiters, alternately fawning and insolent, in the worst type of “posh” hotel would have seemed to the ancients typically servile; the kind, unpretentious old servants whom men of my age can still remember (especially in the country) would not. —Studies in Words, ch. 5: Free, pp. 112, 114

If anybody still remembers Downton Abbey, the distinction is also nicely highlighted by the differences in character between Thomas Barrow (a servile character in the ancient sense) and Mr. Bates (not).

These conceptualizations were, of course, true and fair. After all, they had been put forward by intelligent and respected slave-traders and slave-owners—obviously disinterested parties who raised the matter at all purely out of intellectual curiosity.

A young slave holds back his drunken master’s

hair while the latter vomits. Early fifth cent. BC

Attic pottery; photo by Stefano Bolognini, used

under a CC BY-SA 3.0 license (source).

… And Why They Matter

The reason all of this matters is, when Jesus and the apostles talk about slaves in the New Testament, the message they’re sending, imaginatively and emotionally, is very different from the message our society primes us to associate with the concept of slaves. It was more along the lines of how we think about convicts today.7 Most people treat them with suspicion and aloofness, if not hostility; everyone acknowledges in principle that there are both wrongly-convicted and genuinely reformed individuals among them, but most people—with a few naive or saintly exceptions—don’t want to listen to protestations of innocence, and just don’t want to deal with convicts in general, at least no more than they have to.

Above all, it definitely wouldn’t be normal or expected or comprehensible for a king, even a mostly ceremonial king like Charles IV,8 to announce that he was adopting a slave as his son’s co-heir. Indeed, you might expect some jealousy from said son! As opposed to, say, the prince going out of his way to befriend the slave in question, assign him massive powers and estates, and actively put not only his reputation but his own life on the line to ensure the slave’s safety. That behavior would be pretty weird.

Finally, I’m sure it’s just a coincidence that, of the two stereotypes of servile character, the more morally flattering one is not the one that prevailed when Jesus was teaching his disciples. Or that those of his parables which involve slaves are so often lessons about generosity and compassion—he’s probably not doing everything in his power to hammer home how important those things are, right?

This leaf from a Gutenberg Bible has no

comment to make

Footnotes

1The Greek term used is φιάλη [fialē], the origin of the English word “vial” (via the archaic form phial, to which the same thing happened as in the name Stephen). A φιάλη was a type of dish, similar in form to a shallow bowl or deep saucer, and was used in antiquity for making libations, i.e. drink offerings. Part of the difficulty in selecting a good translation is that we don’t really do libations anymore, unless the athletic tradition of Gatorade showers counts (but the dish used in that procedure is quite dissimilar from the φιάλη in form).

2That concept, and modern racism with it, didn’t fully develop until the eighteenth century. It is partly the work of Kant, who was an eminent anthropologist in his day; he introduced a theory of four races with inherent qualities based on the theory of the four humors—an interesting index of what the word “scientific” means in “scientific racism.” (To do the man justice, he came to oppose racial hierarchy, or at least its colonial implications, in the last years of his life. But of course no one was going to listen to Immanuel Kant, the moralizing intellectual; they had already heard what they wanted to hear, and from no less than Immanuel Kant, the outstanding scientist.)

3I realize this clause can be read in two ways, but the one we’re focusing on is the social-inculturation one, not the military one!

4Attic, besides the other thing, means “from Attica” (the peninsula on which Athens sits).

5Surprisingly, and to the world’s great misfortune, Aristotle of all people was an exception to this. Now, the ethnicities he considered fit for slavery were “everybody who isn’t Greek,” and this may (or may not) mean he wasn’t being entirely serious; it certainly does mean that his idea was not adopted straightforwardly by subsequent justifiers of slavery. But even after those allowances have been made, his enormous influence still contributed to the formation—and worse, the tenacity—of modern racism.

6This may, at a glance, seem to run counter to the idea that no ethnicity was viewed as inherently “slave material.” The difference is, this was a punishment specifically of Carthage, following a war that was (rightly or wrongly) considered the Carthaginians’ fault. Phoenicians as such—the ethnicity to which Carthaginians belonged (they came originally from Tyre)—did not have this penalty applied to them for just being Phoenician, either at the time or in later Roman history.

7Which, hoo boy, is a loaded remark in a discussion that touches on American slavery! I’m talking about the way most of us unreflectively think about convicts, for the sake of getting an idea of the imaginative and emotional picture Jesus’ words would have painted, because that picture is worth understanding. It is still true that the way most of us unreflectively think about convicts could, to put it mildly, also use some critique!

8Or “Charles III,” as he is more widely known in Great Britain, ignoring the Charles III who already reigned by right (and if I recall correctly, British law does mandate that the crown passes automatically to the rightful heir, so there’s no good dithering over the Bonny Prince’s failure to capture London). Having thus pleased the four Jacobites in existence, I must also advise them them that the idea the British crown could only pass to a Catholic is as silly as the idea that banning Catholics from it is in any way a just law; and, after the death of Charles III Stuart, the next-closest relative in the succession, if memory serves, actually was the man who reigned under the name George III, even if he should have been numbered George I.