Who Is This Child Anyway?

The Gospel for the Twentieth Sunday after Trinity (a.k.a. the Twenty-eighth in Ordinary Time) is the next one coming up. It also so happens to be a fairly concise one—a lot of our remaining pericopes from Mark are—so I found I was able to knock out translation and commentary rather briskly.

Christ and the Rich Young Ruler (1889)

by Heinrich Hoffman

The identity of “the rich young ruler” is a minor puzzle of the Synoptic Gospels. Our text, from Mark, says nothing about him; Matthew informs us that he was a νεανίσκος [neaniskos], a young man, probably in his twenties; Luke alone gives us the vague description that he was an ἄρχων [archōn], “a ruler,” which might apply to almost anyone who held religious or political office in contemporary Judæa.

In classical usage, particularly in Athens, an ἄρχων was a magistrate; this might imply that the young man in question was of local rather than Roman extraction, and might also suggest that he was a local landowner with substantial holdings, as opposed to a dynast of the Herod family. To be clear, the language doesn’t rule out a man older or a very little younger than his twenties, or a Roman, or a Herod. Technically, it could even apply to Herod Agrippa I, who had grown up in Rome and returned only a few years ago, and was at this time living modestly to the south of Jerusalem with his new wife, Cypros—it’d be a stretch, but not impossible. But, since Herod Agrippa I is the Herod of the book of Acts, it would be strange for Luke not to mention who he was here, especially since even the most conservative estimates don’t date Luke earlier than the late 50s, when Agrippa had already been dead for over ten years. Besides, really, almost anybody with official position would fit the bill.

I came across one or two off-the-wall ideas while researching this, one being the notion that Paul of all people was the rich young ruler, despite the fact that, as far as I can tell, our grand total of evidence for this is that Paul’s family may have been fairly well-off to provide him with such a good education! To say nothing of the fact that Paul’s conflict with the infant Church in Acts 7-9 appears to be entirely theological and halakhic, and detachment from wealth does not seem to have played a prominent role in his conversion, something Luke of all people would have mentioned.

But there is a theory—unavoidably tentative, but perfectly possible—that Mark the Evangelist himself is the rich young ruler.* We are informed in Acts 12 that during St. Peter’s captivity, “many were gathered together praying” at “the house of Mary the mother of John, whose surname was Mark,” implying the family was wealthy enough to accommodate large gatherings …

St. Mark’s Monastery, said to be John Mark’s

mother’s house, in the Armenian Quarter** of

Old Jerusalem. Photo uploaded by Wikimedia

user momo, under a CC BY 2.0 license (source).

“Is Your Name Not Bruce?”

… always assuming it was the same Mark. Oh yes! in addition to the Jameses and Johns and Maries and Salomes (Salomai?) we had to sift through, Marks are problematic now, and everything is terrible, and you’re welcome.

We are used to understanding there to be one Mark, a certain John Mark, in the New Testament—perhaps a kinsman of St. Peter’s and perhaps present in Gethsemane,* a cousin of Barnabas and companion of his and Paul’s, who wavered during the latter’s first missionary journey but was later reconciled with him. It’s a good narrative, and it may be the true narrative. One Mark will meet the requirements, so to speak. The difficulty with this thesis is that it contradicts the primitive tradition: not the infallible tradition of the Church, you understand, so we’re off the hook in that direction, but the tradition in the sense of “subsequent, supplemental data added by the fathers for purposes of clarification.” And since there doesn’t seem to be a reason I can think of that they’d have split this particular guy into multiple identities (nothing, either theological or hagiographic, comes of the tradition—it’s just kind of there), we do have to give it the time of day in the name of intellectual thoroughness.

Sculpture of St. Mark the Evangelist atop his

basilica in Venice. Photo by Petar Milosevic,

used under a CC BY-SA 4.0 license (source).

Unfortunately, “John” and “Mark” were two of the commonest Jewish and Roman names at the time, and it was standard practice, then as now, for Jews who had any significant dealings with Gentiles (as not all but most did) to have a Hellenized by-name alongside their Hebraic name. Tradition supplies us with no fewer than three Marks. One of them is John Mark, the St. Mark who is supposed to have written this Gospel and become the first Bishop of Alexandria. He is (allegedly) not to be confused with John Mark, the cousin of Barnabas, known to us from Acts 12.25, 13.13, and 15.36-40, who became the Bishop of Apollonia (located in what was then the Roman province of Illyria, and now lies on the coast of Albania). And obviously, neither of these should be confused with John Mark, the first Bishop of Byblos, a little north of Beirut. It will of course come as no surprise that all three of these young men are supposed to have been among the Seventy Apostles commissioned in Luke 10—just like the other Cephas who apparently wasn’t St. Peter, and of course the two discrete figures of St. Silvanus and St. Silas, or the two different Barnabases, because church history hates you, personally.

There is, however, a saving grace here that I had nearly forgotten: it doesn’t matter. The lesson of this passage is the same whether it’s about someone anonymous, or John Mark, or John Mark, or even John Mark. So let’s get on with it.

Mark 10.17-30, 31, RSV-CE

And as he was setting out on his journey, a man ran up and knelt before him, and asked him, “Good Teacher, what must I do to inherit eternal life?” And Jesus said to him, “Why do you call me good? No one is good but God alone. You know the commandments: ‘Do not kill, Do not commit adultery, Do not steal, Do not bear false witness, Do not defraud, Honor your father and mother.’” And he said to him, “Teacher, all these I have observed from my youth.” And Jesus looking upon him loved him, and said to him, “You lack one thing; go, sell what you have, and give to the poor, and you will have treasure in heaven; and come, follow me.” At that saying his countenance fell, and he went away sorrowful; for he had great possessions.

And Jesus looked around and said to his disciples, “How hard it will be for those who have riches to enter the kingdom of God!” And the disciples were amazed at his words. But Jesus said to them again, “Children, how hard it is for those who trust in riches to enter the kingdom of God! It is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for a rich man to enter the kingdom of God.” And they were exceedingly astonished, and said to him, “Then who can be saved?” Jesus looked at them and said, “With men it is impossible, but not with God; for all things are possible with God.” Peter began to say to him, “Lo, we have left everything and followed you.” Jesus said, “Truly, I say to you, there is no one who has left house or brothers or sisters or mother or father or children or lands, for my sake and for the gospel, who will not receive a hundredfold now in this time, houses and brothers and sisters and mothers and children and lands, with persecutions, and in the age to come eternal life. But many that are first will be last, and the last first.”

Mark 10.17-30, 31, my translation

And as he was going out onto the road, someone ran up and knelt to him and asked him: “Good teacher, what will I do so that I will inherit eternal life?” Jesus said to him: “Why do you called me ‘good’? No one is good, except the one God. You know the charges: ‘You will not kill,’ ‘You will not commit adultery,’ ‘You will not steal,’ ‘You will not give false testimony,’ ‘You will not defraud,’ ‘Honor your father and your mother.'”

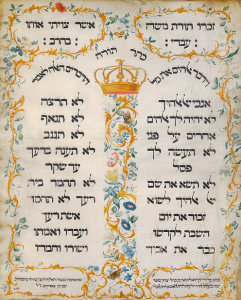

The Decalogue, written on parchment in 1768

by Jekuthiel Sofer, in imitation of a copy from

the Portuguese Synagogue in Amsterdam.

He told him, “Teacher, I was on my guard about all these things from my youth.” Then Jesus, looking at him, loved him and told him: “This is missing in you: go sell what you have and give to the poor, and you will have treasure in heaven, and come follow me.” But at this, he was sullen and went off grieving, for he had many things.

And, looking around, Jesus told his students: “How difficult it is for those who have possessions to come into the kingship of God.” His students were astonished at these words of his. So Jesus, responding again, told them, “Children, with what difficulty they come into the kingship of God: it is easier for a camel to come through the eye of a needle than for a rich person to come into the kingship of God.”

They were exceedingly shocked, saying to each other: “But who can be saved?” Looking at them, Jesus said, “It is impossible to humans, but not to God, for all things are possible to God.”

Rocky began to say to him: “Look, we have let go of everything and followed you.” Jesus told him: “Amen, I tell you, there is no one who has let go of household or brothers or sisters or mother or father or children or fields for my sake and the sake of the good news, who will not receive a hundredfold now in this time in households and brothers and sisters and mothers and children and fields, with persecutions, and in the age that is coming, eternal life. And many will be first who are last, and the last first.”

Textual Notes

a. what must I do to inherit/what will I do so that I will inherit: There is no hint of uncertainty on the young man’s part that, whatever it is, he will do it and will inherit eternal life. (This shouldn’t be overblown; there were more modest ways to phrase this in Greek, but the future indicative could indicate purpose—it hits as a little bold, not as enormously conceited.)

b. You know … and your mother: Matthew appends “You shall love your neighbor as yourself,” while leaving out “Do not defraud.” Luke only includes the direct quotations from the Decalogue.

c. his countenance fell/he was sullen: The verb (or more exactly, participle) here, στυγνάσας [stügnasas], is actually related to the name of the River Styx, which means “hateful.” It’s interesting that our translations so regularly soften this, making him sad but taking out the note of resentment the text suggests.

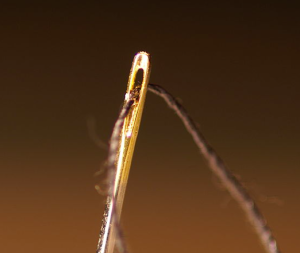

The eye of a needle. Photo by Deron Meranda,

used under a CC BY-SA 3.0 license (source).

d. a camel to go through the eye of a needle/a camel to come through the eye of a needle: I get the impression that this legend is, mercifully, going extinct; but, to head it off at the pass for anyone who hasn’t heard: while there may have been a “Needle’s-eye Gate” in Jerusalem that camels were too big to get through, if this gate ever did exist (which it probably didn’t), it was never mentioned until a thousand years after Jesus made this pronouncement. YouTuber Religion for Breakfast has quite a good video on this exact text, going into both this theory and a second that has better scholarship behind it.

This second theory is the idea that some early copyist made a typical scribal mistake, confusing κάμηλος [kamēlos], “camel,” with the visually and audially similar κάμιλος [kamilos], “cable” or “rope” (which may come across as more logical, since pulling a rope through the eye of a needle, while still impossible, is the same sort of task as pulling a thread through; apples to apples instead of to oranges, as it were). However, there are strong objections to the “rope” reading. Only a small number of manuscripts have such a reading, and those that do are late, Byzantine-family texts, whereas our earliest witnesses unanimously read “camel”; the confusion would only be possible in Greek, not Aramaic; there is a parallel saying in the Babylonian Talmud about impossible things like “an elephant passing through the eye of a needle”; and—in my opinion, fishiest of all—even if it is also impossible to get a rope through the eye of a needle, it doesn’t feel as impossible as getting a camel through; emotionally, it’s a softening of the rhetoric, no matter how rationally equal in impossibility the two procedures might be. That alone ought to rouse our suspicions, given that we are, by any meaningful measure in world history, among the wealthy ourselves.

Don’t worry! I counted, there’s only nineteen

there and they’re not even real coins.

Nothing to worry about.

e. or mother or father or children … and mothers and children: Strikingly, the disciples are not promised a hundredfold in new fathers.

*It is Matthew, not Mark who uses the term νεανίσκος, so it is exceedingly risky to try and make this a “load-bearing” detail. However, Mark 14.51-52, which is also widely interpreted as an allusion by the evangelist to himself, also describes the man dressed only in a linen cloth as a νεανίσκος. Is it possible that the “rich young ruler” did after all resolve to sell what he had, give to the poor, and come and follow Jesus—only to discover that he had chosen just about the worst moment possible to do so? (A possible snag in this interpretation is that it lands us with the problem of how he knew to look for Jesus on Mount Olivet, which seems to have been a relatively clandestine camp-site, since the conspiring portion of the Sanhedrin needed an insider to take them there.)

**The “quarters” of the Old City (“districts” would be the modern term, as they are nowhere close to equal and never were) are the Muslim Quarter in the northeast, the Christian Quarter in the northwest, and, both in the southwest, the Jewish and Armenian Quarters. Why the Armenians were thus separated from the rest of the Christians, I don’t know, unless it was because the bulk of the Armenians followed the Armenian Apostolic Church, which was out of communion with both the Latin Catholics and the Orthodox Melkites when the Crusaders showed up, and had been for far longer than they had been out of communion with each other. (There used to be a very small Maghrebi, or Moroccan, Quarter too, located in the southeast—again, not clear why they got separate billing from fellow Muslims—but this was destroyed during the Six Day War in 1967.)