A Few Words on How to Bible Real Good

Choosing a good Bible for devotional use, study, or both can be difficult, and the differences between translations can be confusing. Some variation makes sense, sure—but when you’re listening to a sermon on John 8.1-11, and you open up your own Bible to follow along, only to discover it hasn’t got a John 8.1-11 … I mean, how does that even happen?

A page from a Gutenberg Bible

Short version: the manuscripts our Bibles are translated from don’t a hundred percent agree with each other. Now, some people freak out about this; to them, it sounds very modern and skeptical and Bart D. Ehrman to say that sort of thing. So it may be helpful to explain a few things.

There are texts from the ancient world—Æschylus’s Oresteia trilogy, for example—that have been edited and emended so many times, we flat-out can’t know what the original text said based on what survives. If we one day uncover older evidence, that might let us establish get closer to the Oresteia as Æschylus wrote it (or, maybe not), but as things are, some texts will just have to be accepted as uncertain.

The reason Ehrman gets under my skin so badly is that, while he has made a modest literary career of implying that the New Testament and its constituent parts are among these texts, they’re not. Variants exist, but none of them radically alters either the total message of the book they’re a part of, or even the meaning of the part of the book they occur in; a lot of the variants that do exist are along the lines of “This complete copy of Ephesians from this famous tenth-century library has a period between these two words, but this fragment of the same passage from this renowned seventh-century cathedral has a colon instead.” The closest we get to serious differences are in passages like John 7.53-8.11 or the notorious Johannine Comma (I John 5.7b-8a), and there is little to no serious uncertainty among scholars about whether these passages are authentic.1 To understand this a little better, let’s dip into some of the principles of what’s called textual criticism, the science behind our understanding of all ancient documents.

A Textus Sayswhat?

Qumran Cave 4, the location in which 90%

of the Dead Sea Scrolls were discovered.

Photo by Effi Schweitzer.

In establishing the original text of any ancient document, manuscript witnesses are used. “Witnesses” in this context means ancient copies of a text, and a copy counts as “ancient” for these purposes as long as it predates the printing press. We rely on copies because the original documents, or autographs, have in all likelihood been dust for several hundred years by now. There are usually anything from just one to a few dozen witnesses—sometimes hundreds, for a particularly well-attested document (e.g. the Iliad). Occasionally, these manuscripts survive complete; most are damaged; many survive only in fragments. (Part of the reason the Dead Sea Scrolls were so exciting was that they were not only extremely well-preserved witnesses to the Old Testament’s2 text, but older copies than anything else we possessed.)

When it comes to the New Testament, we are on exceptionally firm ground—in fact, it’s the best in the business: the witnesses for the New Testament number in the thousands. Unluckily, this also means we have a lot of material to sort through. Some broad categorizations will be needed!

Manuscripts can be loosely grouped in “families” (or as scholars call them, text-types). Imagine a scribe creating a new copy of Ephesians, say, and he accidentally makes that colon-period swap we mentioned before. Anybody who copies Ephesians from his copy is going to have the same error in the same place, unless they just happen to correct it back by chance (which is possible, but no more likely than just making a fresh error of their own); on the other hand, anybody who copies the text from a different copy of Ephesians probably won’t contain that error. And since there are general tendencies about everything, even errors, in any given culture or intellectual center, this leads to the formation of distinguishable “lineages” of manuscripts.

The New Testament has at least three general text-types. (A fourth type, “Cæsarean,” has been proposed; if it is a valid grouping, the Cæsarean family may owe something to the work of the great Biblical scholar Origen.)

- The Alexandrian, often preserving shorter or more difficult versions of the text. Their high reputation is based in part on a rule in textual criticism3 called lex difficilior potior: “the more difficult [version] is the stronger [candidate for being the original].” Modern printing errors are mostly mechanical and therefore nonsensical; mistakes made by scribes, on the other hand, involve a human mind, and one error scribes are prone to is thinking ‘That can’t be right’ and “correcting” a text that seems faulty; the thing is, they’re more likely to seek to resolve difficulties than they are to introduce new ones. The Alexandrian family also boasts many of the oldest witnesses: the city of Alexandria, between the Nile and the Mediterranean, was humid, and so not a great place to keep scrolls intact,4 but there was plenty of conveniently near-at-hand desert, a climate just about ideal for preserving scrolls. Brooke Foss Westcott and Fenton Hort were two of the first scholars to work on, and declare a definite preference for, the Alexandrian text over the Textus Receptus; their edition is sometimes called the Westcott-Hort text.

- The Western, perhaps the most frustrating family of the bunch (the Vetus Latina or Old Latin Bible, which St. Jerome was tasked with revising into the Vulgate, was a Western Bible in this sense too). Western witnesses have a great tendency to rearrange, paraphrase, and even add words that will bring out the meaning more forcefully. But even the Western text-type is not considered the least-reliable—that dubious honor goes to …

- The Byzantine, also called the “Majority Text” (since most of our witness do happen to be Byzantine in type), or occasionally “Syrian.” These tend to display smoother Greek, have longer and less difficult readings, harmonize their parallel passages in the Synoptic Gospels—that sort of thing. Most modern scholars therefore consider the Byzantine type the most interfered-with (though a vocal minority of scholars, especially in the US, argue against this). The Textus Receptus, which was the first-ever critical edition5 of the New Testament, published by Erasmus in 1516, is basically Byzantine, and the King James relies on the Textus Receptus.

To be clear, this is not as simple as a sliding scale of “good” to “bad” where Alexandrian manuscripts are always better and Byzantine ones are always worse. Almost no modern Bible is just a translation from one family. The Alexandrian preference for concision could lead to wrongly omitting material, after all, just as the Byzantine preference for harmony could lead to wrongly smoothing out uncomfortable passages. Most modern translations survey all different families and make judgment calls about individual discrepancies among them, perhaps favoring one family or another but not sticking to any one absolutely; this approach is known as textual eclecticism, and is a standard approach to most works with a substantial history that predates the printing press.

I lay all this out, because the text of Mark 10 is the sort of place where Alexandrian and Byzantine editions of the Gospel are likely to differ; and they do differ. Funnily enough, they do it right from v. 2.

Jesus’ Teaching on Divorce

A Russian ikon of the Blessed Virgin

under the “burning bush that is not

consumed” motif

Most people probably know already that, according to the Catholic Church, the circumstances in which divorce is permitted are “no.” Many people also know vaguely about annulments, which are widely understood as “Catholic divorce”; this idea is simultaneously incorrect and correct, but, I’m sorry, I’m not getting into it.

The reason why not is, I don’t have to put up with the consequences of this teaching. The only thing I could contribute is restating what the teaching is, when (i) it’s perfectly easy to look that up in the Catechism, and (ii) I have no special insight to offer about fulfilling the duties a belief in the indissolubility of marriage imposes on the married. That belief can be extremely costly; especially for people who are forced to deal with a spouse who is abusive (physically or otherwise), or adulterous, or catastrophically irresponsible with money, or has substance abuse issues. But I’m never going to have to “foot the bill” for my belief in the indissolubility of marriage. And if there’s anything I can’t stand, it’s people who hear secondhand about situations that may be confusing or painful to the pitch of nightmare, and then respond by reciting the context-less doctrinal and ethical formulæ of the Catholic faith. As if those formulæ were the answer to the agony of the situation, instead of, you know, the thing that makes the situation agonizing. Because if you were morally justified in doing whatever you felt like, there wouldn’t be a situation, would there? “They bind up heavy burdens, but they themselves will not move them with one of their fingers.” I don’t want to be that person.

Right Here Right Now

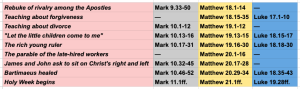

But, there is more to say about this text than just repeating or not repeating Catholic teaching about whom man ought or oughtn’t put asunder. Matthew and Mark both present this teaching on divorce as part of Jesus’ slow progress toward the Triumphal Entry, alongside a few other elements (some but not all of which are shared with Luke, though his chronology seems much less cohesive), as exhibited in this merry little chart:

I’ve wondered vaguely before now why the topic of divorce comes to the fore so close to the beginning of Holy Week; it might come across as a little arbitrary. It crossed my mind to wonder if there were some hint here at the idea of the mystical marriage between Christ and the Church, since the New Covenant was about to be set forth and ratified by the Last Supper, Passion, and Resurrection.

Looking at it, though, I’m not sure that interpretation works. At least, not on a typical idea of the distinction between the Church and the people of Israel. Israel was clearly “God’s bride” at the time Jesus actually gave this teaching; his rejection of divorce would seem inconsistent with the picture of God taking a new bride. Unless Christians are meant to see Israel and the Church as far more profoundly one than they’re usually painted, which might line up with Paul’s discussion of Israel in Romans 10-11—but that would require a theological analysis that I am not capable of doing on the fly!

Tomorrow’s passage comes in both short and long forms; basically, the lectionary allows us to leave off the last four verses, for a singly-themed Gospel text. I’ve included them in my translation as usual, and thrown in verse 1 because why not.

Mark 10.1, 2-12, 13-16, RSV-CE

And he left there and went to the region of Judea and beyond the Jordan,a and crowds gathered to him again; and again, as his custom was, he taught them.

And Pharisees came up and in order to test him asked,b “Is it lawful for a man to divorce his wife?” He answered them, “What did Mosesc command you?” They said, “Moses allowed a man to write a certificate of divorce,d and to put her away.” But Jesus said to them, “For your hardness of heart he wrote you this commandment. But from the beginning of creation, ‘God made them male and female.’ ‘For this reason a man shall leave his father and mother and be joined to his wife, and the two shall become one.’ So they are no longer two but one.e What therefore God has joined together, let not man put asunder.”f

And in the house the disciples asked him again about this matter. And he said to them, “Whoever divorces his wife and marries another, commits adulteryg against her; and if she divorces her husband and marries another, she commits adultery.”

†

And they were bringing children to him, that he might touch them; and the disciples rebuked them. But when Jesus saw it he was indignant, and said to them, “Leth the children come to me, do not hinder them; for to such belongs the kingdom of God.i Truly, I say to you, whoever does not receive the kingdom of God like a child shall not enter it.” And he took them in his arms and blessed them, laying his hands upon them.

Mark 10.1, 2-12, 13-16, my translation

And rising from that place, he came to the hills of Judæa and across the Jordan,a and again crowds were gathering around him, and he began to teach them, as he habitually did. They were asking him if a husband were allowed to divorce his wife, testing him.b He replied and said to them: “What did Moshehc command you?” They said, “Mosheh permitted writing a desertion-bookd and divorcing.”

A 16th-cent. illumination of unfallen Adam

and Eve from Safavid Persia. (Don’t ask me

where that guy tapping the side of Adam’s …

dragon? … with a stick came from, I dunno.)

So Jesus told them, “For your hardened hearts, Mosheh wrote you this charge. From the beginning of creation, ‘He made them male and female’; ‘for this reason a person will leave his father and mother and be glued to his wife, and they two will be in one flesh’; so they are no longer two, but one fleshe: what God, then, yoked together, do not divide, human.”f When they were in the house again, his students asked him about this. And he said to them: “Whoever divorces his wife and marries another commits adulteryg against her, and if a woman has divorced her husband and marries another, she commits adultery.”

†

And they were bringing him small children, so that he would lay hands on them; but his students rated them. But, seeing this, Jesus was indignant, and told them, “Permith small children to come to me, do not restrain them; for the kingship of God is of these kind.i Amen, I tell you, whoever does not receive the kingship of God like a little child—he will not come into it.” And taking them in his arms, he put his hands on them and blessed them.

Textual Notes

a. beyond the Jordan/across the Jordan: What is now the western edge of the Kingdom of Jordan (the East Bank, so to speak) was then known in Greek as Περαία [Peraia], now typically written “Perea”—which almost literally means “Over There.” It had (according to the Tanakh) been part of the Kingdom of Israel, both in its united phase under its first three-ish kings, and in the period of the divided monarchy; the tribes of Reuben, Gad, and Manasseh were supposed to have land on that side of the Jordan. At this time, Perea was ruled by Herod Antipas, also known as Herod the Tetrarch—so named because, after Herod the Great’s death, his former kingdom had been split four ways by the mediation of Rome: Judæa and Samaria had gone to Herod’s principal heir, Archelaus (the one whom St. Joseph wanted to avoid on coming back from Egypt); Perea and the Galilee went to his brother Antipas; their half-brother, Philip, received the territory northeast of the Sea of Galilee, squeezed in between the Decapolis and the bulk of the province of Syria; and Herod the Great’s sister, Salome, received a few cities on the coast and one on the western bank of the Jordan.

The Herodian tetrarchy, ca. 30 AD. Pink: Judæa;

purple: Antipas; orange: Philip; green: Salome;

Roman Syria: yellow. Image by DEGA MD, used

under a CC BY-SA 4.0 license (source).

The realm of Herod Antipas—the King Herod of most of the Gospels—was a little removed from the political sensitivity of Judæa proper and the ethnocultural resentments of Samaria; the Pharisees had influence throughout his kingdom. This formed a mild contrast with the Judean heartland, which was somewhat more evenly divided between themselves and the Sadducees (as well as being, at this point, under direct Roman rule in the person of Pontius Pilate—Archelaus had been deposed and exiled several years into his incompetent reign).

b. And Pharisees came up and in order to test him asked/They were asking him … testing him: Here, we have a difference in manuscript traditions: the Westcott-Hort version of the Greek, which leans toward Alexandrian readings, and the Textus Receptus both—a formidable combination!—include specific mention of Pharisees here.

However, I’m inclined to agree with the decision made in the text supported by the Society of Biblical Literature (which I’ve been using throughout). Jesus being tested—which may or may not indicate hostility—by mere bystanders is rather unusual, meaning this reading aligns at least in some degree with the lex difficilior principle, and it would be natural for a copyist to supply the characteristic antagonist.

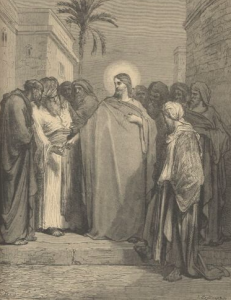

Dispute Between Jesus and the Pharisees

(1866) by Gustave Doré

c. Moses/Mosheh: Our version of the name comes via Latin from the Greek form, Μωϋσῆς [Mōüsēs]. The original Semitic form, common to Hebrew and Aramaic alike, is מֹשֶׁה [Mosheh].

d. certificate of divorce/desertion-book: When we read in Deuteronomy that a husband must write his wife “a certificate of divorce,” this may give us the impression that it’s up to him what to write as long as he puts “a certificate of divorce” at the top. This isn’t at all how divorce worked, or what that text in the Torah or this one in the Gospel is saying. They’re talking about a legal document of a form that already existed, something called a גֵּט [gēṭ] (still in use among Orthodox Jews).

People don’t often think of the ancient world as legally sophisticated, but it very much was—it was litigious, even. If this seems confusing, consider for a moment how much less there was to do. Then, to back it up, think if you like about some phrase like “the Code of Hammurabi,” which not only dealt with marital law but (even on a highly literal and conservative calculus of the dates) was already hoary with age when the earliest form of the Torah was drafted. A gēṭ had a particular, set form; moreover, then as now, divorce was generally frowned upon among Jews, even though it was permitted. Its requirements for validity are strict, though fulfillable: witnesses are required; the divorcing husband (and yes, it does have to be the husband) must physically hand the gēṭ to his wife; and the process must take place before a beth din, a rabbinical court, a little like the tribunal of a Catholic diocese.

Part of the Louvre stele incised with

Hammurabi’s Code in cuneiform.

Photo by Mbzt, used under a CC

BY-SA 3.0 license (source).

One of the controversies in Jesus’ own time was what grounds, if any, were required for issuing a gēṭ. In particular, within the Pharisaic party—to which, remember, Jesus belonged—there was a dispute between the slightly older interpretive school of Hillel the Elder (Beyt Hillel), who generally favored a “generous” or “relaxed” approach to the Torah, and the increasingly popular school of Shammai (Beyt Shammai), Hillel’s younger contemporary and colleague, whose interpretive method was more rigorist. Beyt Hillel allowed a husband to issue a gēṭ for more or less any cause; Beyt Shammai, on the other hand, effectively required adultery to justify divorce. (Modern Judaism, whether Orthodox or Reconstructionist or anything in between, basically aligns with Beyt Hillel to this day; strictly speaking, as little as mutual consent suffices for the issuance of a gēṭ. Social rather than religious strictures keep divorce rates low among practicing Jews.)

What’s particularly interesting in this text is that Jesus, who tends to line up with Beyt Hillel most of the time, comes down hard in favor of Beyt Shammai—something he does exceedingly rarely. I can’t name even one unambiguous parallel. His reasoning, rooted in the creation pattern and re-characterizing Moses’ own provision as a concession rather than a command proper, is also striking, and I’m not sure I can think of a clear parallel to that, either.

e. “the two shall become one.” So they are no longer two but one/”they two will be in one flesh”; so they are no longer two, but one flesh: Below is the Greek text, accompanied by a transliteration and a hyper-literal, word-by-word translation:

ἔσονται οἱ δύο εἰς σάρκα μίαν· ὥστε οὐκέτι εἰσὶν δύο ἀλλὰ μία σάρξ

esontai hoi düo eis sarka mian: hōste ouketi eisin düo alla mia sarx

they-will-be the two into flesh one: so-that no-more they-are two but one flesh

I go out of my way to provide this for two reasons. One, the literal phrase “they will be into one” is quite charming to me. The other reason is, I find the RSV’s not translating σάρξ, either time it occurs in this passage, very strange—even if, for some reason, they didn’t want to use the literal translation “flesh,” “body” or “being” might have done.

Yoked oxen pulling a cart in modern India.

Photo copyrighted by Yann, used under

a CC BY-SA 4.0 license (source).

f. What therefore God has joined together, let not man put asunder/what God, then, yoked together, do not divide, human: The “yoke” language is of course an agricultural trope about marriage (doubtless more familiar to many evangelicals due to St. Paul’s remarks in I Corinthians about “not being unequally yoked”). It hadn’t struck me before how this image emphasizes not just cooperation, but cooperation with a specifiable goal in mind, and indeed in sight.

My clumsy “do not divide, human” (vastly inferior prosody to “let not man put asunder”) is an attempt to convey two things: first, the third-person imperative which this verse closes with, something we’ve discussed in a few other passages; and second, the use of ἄνθρωπος [anthrōpos] rather than ἀνήρ [anēr]. The latter means “man” or “husband,” whereas the former is a generic word for “person, human being,” without suggesting one gender over another: ἀνήρ is “man as opposed to woman,” set against ἄνθρωπος’s “man as opposed to ape or angel,” if you will. In consequence, the ἄνθρωπος- ἀνήρ distinction is noticeable in this passage.

A Coptic Christian woman from the early

twentieth century. Photo by Dittrich P., used

under a CC BY-SA 2.5 license (source).

My guess, though I emphasize that it is a guess, is that this is meant to underline a presumptuousness implied in the concept of divorce. (To be clear, I’m speaking here about divorce considered as a religious act, entitling a person to remarry freely—the same rules do not necessarily apply to civil divorce. Civil divorce can be a prudent, even a necessary, means of protecting oneself and one’s children from an abusive spouse or their family, for example.) This is a unique sacrament: its first roots lie in creation before there was any need for redemption, and it calls for the ratification of God for a mystery effected by the spouses themselves. To think we can just revoke that—?

g. commits adultery: The verb here is μοιχάω [moichaō], which refers specifically to that act. It is not the word employed in the parallel text in Matthew 19.9, where it permits divorce “for unchastity,” as the RSV-CE has it; the verse does go on to say that a husband who divorces his wife for any reason except “unchastity” has μοιχάω’d against her, but that’s different.

The “unchastity” allowance is over a different word: πορνεία [porneia]. Etymologically, this just means “whoring”—no frills; somehow vague yet blunt at the same time, a quality Greek is rather good at as a language. However, the word comes in subsequent use to mean something like, well, “unchastity” as a catch-all term. This technically includes adultery of course, but at the same time, in terms of what we might call rhetorical temperature, it definitely does not include adultery. This is why Catholic Bibles sometimes render this verse “unless the marriage is invalid,” interpreting πορνεία as a reference to incest, and the allowance as addressed to couples who discover after the fact that they have a degree of kinship too close to contract a valid marriage.

Personally, I don’t like the “unless the marriage is invalid” translation. It is absolutely a possible interpretation of the text, and moreover, one that I am both inclined to accept as a scholar and duty-bound to accept as a Catholic. But to present that as a translation of the text, rather than making it a note for the reader about how to properly interpret the text, borders in my opinion on untruthfulness.

Incidentally, a good lesson in “sentences never to listen to” is also available here. Obviously we know what the English noun adultery means (namely, behaving … like a very specific kind of adult). But, because the naturally corresponding verb to adulterate doesn’t mean that, and we don’t have another one-word synonym, it would be technically correct (the best kind of correct) to say “English has no word for ‘to commit adultery’.” The thing is, that fact is obviously not significant. We have at least two set phrases which mean that: commit adultery for formal registers, and cheat on for informal ones. The fact they don’t happen to be individual vocab items tells you nothing at all about how English as a language works, or the psychology of English speakers, or any of that tripe. So, yeah—next time you hear that such-and-such a language “doesn’t even have a word for” anything, just remember: even if that person’s claim is correct (and really, I bet it’s not), it’s meaningless.

The Lord’s Prayer (1850), James Tissot

h. Let/Permit: The verb here is the same as the verb “to release, let go of, unhand; to forgive, cancel.” I therefore opted for a translation that at least sounded fairly close to “remit.”

i. to such belongs the kingdom of God/the kingship of God is of these kind: The RSV’s “belongs” here bugs me a little. It probably is a sound interpretation—but again, it is interpretation. The grammar just makes the kingdom of heaven “of” the above-mentioned children, in some unspecified way.

Footnotes

1The answers in those two cases are a “soft ‘no'” for John 7.53-8.11, which is probably an unintentionally misplaced passage that originally belonged in Luke, and a hard “are you kidding me” for the Johannine Comma.

2I say “Old Testament” advisedly: many books found there were not included in the Masoretic Text (the authoritative Hebrew text of the Tanakh), e.g. Sirach and I Maccabees. Some were quite out of the orbit even of common “bonus” material from the Septuagint, like the Book of Jubilees or the War Scroll.

3There are several rules textual critics use to judge what the original form of a text was, lex difficilior being just one. Others include lectio brevior (“the shorter reading [should usually be preferred]”), based on the empirical observation that scribes tended to add words more often than they deleted them (by unthinkingly “completing” set phrases, for example, or accidentally copying marginal notes into the text itself). There were also exceptions to the lectio brevior rule, though. Many were caused by homoioteleuton and homoiarche, or “same ending” and “same beginning”: in other words, if the last few or first few words of two nearby lines were the same, a scribe would be more prone to accidentally return to the wrong point in the text, accidentally deleting the intervening material.

4This is especially true of papyrus. Parchment (which is made from animal skins, whereas papyrus was made from the papyrus reed) tolerates humidity slightly better; papyrus tended to become much more friable as it aged. Naturally, parchment was developed later, meaning that all our oldest documents, the ones that would be the most vulnerable anyway, are on papyrus.

5A “critical edition” does not mean critical in the sense of “negatively judgmental, harsh.” Rather, it is an edition that includes a critical apparatus, i.e. notes on alternative readings to the one chosen by the editors of the volume, and often some account (either in the apparatus itself or in introductory material) of why the editors in question chose the reading they present as likeliest.