The (?) Epistle of John (?)

St. Papias of Hierapolis as depicted in the

Nuremberg Chronicle (1493)—he’s

relevant to this, I promise

Next, we have the Epistle for Hallowmas. This comes from the book we call I John. The letter’s name is based on the traditional belief that it is the first of three letters penned by St. John the Apostle. This, like every other traditional ascription of the books of the New Testament, came under fire in the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries.1 It is now widely believed that I John was written by the same person (or at any rate, one of the same people) who wrote both II and III John and the Gospel of John; that, of course, involves us in the question of who wrote the Gospel, which I’m going to skate over for now. In this post, not because it’s crucial but just because I find it interesting, I’d like to focus on the authorship of these three epistles: for once, I’m the one who’s skeptical of the tradition.2

Here’s why. The Gospel of John and I John are both slow-flowing, ponderous works (even its Resurrection scene is arguably the least-abrupt of the four), a little repetitive, clearly influenced by the rich tradition of Hellenistic Jewish wisdom literature—open the Wisdom of Solomon to any verse at random, it’ll sound like something John’s Jesus could have said. These books aren’t necessarily the work of a professional scholar: they don’t have the meticulous theologico-linguistic sermons of contemporary midrash, for example. They are, however, works of a profound wisdom that is clearly the fruit of long reflection, committed to paper with care and, indeed, with a distinct artistic technique that seems to be self-taught (or at any rate, I can’t think of a halfway-decent parallel in any other literature I’ve read, save only the stuff that was consciously imitating it). They almost feel like they’d invite the invention of illuminated manuscripts.

Epistolettes

II and III John, on the other hand, are really not that. They seem to be written by somebody who doesn’t like writing; by which I mean, they were written by somebody who didn’t like writing, or at least didn’t want to settle for writing:

Having many things to write unto you, I would not write with paper and ink: but I trust to come unto you, and speak face to face, that our joy may be full. —II John 12

I had many things to write, but I will not with ink and pen write unto thee: but I trust I shall shortly see thee, and we shall speak face to face. —III John 13-14

That preference could be dictated by circumstance, yes; but I find it suggestive. It’s unprovable, but to judge from their length (II John, the longer of the two, is only 245 words in Greek), it seems perfectly tenable that they were written as much to avoid wasting leftover scraps of papyrus as anything else! In addition, both letters include formal greetings and address (“the elder to the chosen lady” and “to Gaius”), as well as formal closing salutations; none of these stylistic marks appear in the Fourth Gospel or in I John.

What about the content? Well, both letters, far from being meditative, are extremely to the point. II John appears to be answering a single, straightforward question about Christology: Christ came in the flesh, and anyone who doesn’t agree with that is not one of us. III John gets downright personal, condemning Diotrephes and approving Demetrius (whoever those guys were). These sound like pieces of news, not reflections—fairly urgent news, even. It makes sense that, if the author couldn’t make a journey to another city right at that moment, but needed to answer a pressing doctrinal or administrative question in the community, even if he did dislike writing, he’d be a big boy about it and send a letter anyway.

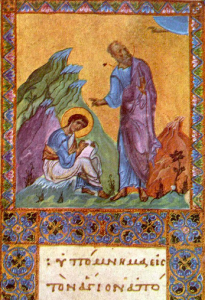

Byzantine illumination (ca. 1100) of St. John

dictating to St. Prochorus.

For an author to vary whether he wants to write depending on circumstances is not unusual. But for an author to vary how he writes in every detail like this—that’s weird. Weird enough that I’m going to call it “implausible.” Not “impossible” by any means. But I don’t see it as a natural assumption to make, and I don’t make it.

“He Shall Take What Is Mine and Declare It to You”

So who did write them? My pet theory starts with information we receive from St. Papias of Hierapolis (which is a delightful name to say). He was one of the earliest Church Fathers, is our ultimate source for several traditions about the first few generations of the faith, and, in a famous passage quoted by the fourth-century Church historian Eusebius of Cæsarea, Papias says the following:

I made enquiries about the words of the elders—what Andrew or Peter had said, or Philip or Thomas or James or John or Matthew or any other of the Lord’s disciples, and whatever Aristion and John the Elder, the Lord’s disciples, were saying. For I did not think that information from the books would profit me as much as information from a living and surviving voice.

As you can see, we have “John” and “John the Elder” (funny, that) in close succession, brought up as if in reference to two distinct people. A couple hundred years later, Eusebius says flatly that they were different people:

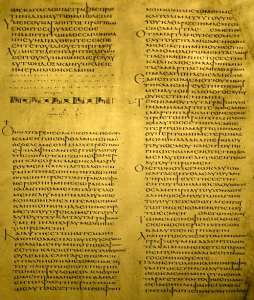

A depiction of Eusebius from a

6th-cent. Syriac manuscript.

… the name John is twice enumerated by him. The first one he mentions in connection with … the rest of the apostles, clearly meaning the evangelist; but the other John he mentions after an interval, and places him among others outside of the number of the apostles, putting Aristion before him, and he distinctly calls him a presbyter. This shows that the statement of those is true, who say that there were two persons in Asia that bore the same name, and that there were two tombs in Ephesus, each of which … is called John’s. It is important to notice this. For it is probable that it was the second, if one is not willing to admit that it was the first that saw the Revelation … And Papias … says that he was himself a hearer of Aristion and the presbyter John. At least he mentions them frequently by name, and gives their traditions in his writings.

John was a very common name, then as now, as we discussed only a bit ago in reference to John Mark (not to be confused with John Mark—no, not that one; you’re thinking of John Mark). It would be extremely natural for there to be another John active in the Church around the same time; Eusebius’ reading of Papias seems like the most obvious one to me, and Eusebius also explicitly confirms not only that there was a pre-existing tradition that John the Apostle and John the Elder were distinct people, but that this tradition was linked even to two distinct tombs. To me, this seems like ample reason to think that there was a St. John the Elder who was not the Apostle of the same name, but was active around the same time and in the same region, i.e. the Roman province of Asia.

A map of Roman provinces in Anatolia under

Trajan (r. 98-117). Created by Caliniuc, used

under a CC BY-SA 4.0 license (source).

My theory makes one additional assumption, which I think is actually easier to sustain than to deny. What if St. John the Elder was an amanuensis for St. John the Apostle? It explains all the similarities in the Johannine corpus—the shared imagery, the half-united style; it simultaneously explains the differences between I John on the one hand and II and III John on the other—the Elder may have been more comfortable as an amanuensis than as an independent writer; it even explains the curious “double vision” we occasionally seem to get in John’s Gospel—when the evangelist seems to be speaking of himself in the third person, maybe that’s actually because there was a third person there with St. John and the Holy Ghost: John’s secretary. Even the uncertainty about whether there was one John or two, which could have arisen in several ways, is more explicable if we suppose that the one was the aide and perhaps successor of the other.

I can only assume that the rough consensus of modern New Testament scholars that these two were actually one single John is based on their most deeply held religious belief: People From Before Were Wrong. It’s more “economical,” but only in the most mechanical sense of that idea imaginable; the theory that we’re all the dreams of a brain in a vat is more “economical,” in that sense, than believing everyday reality is just what it seems to be.

Anyway! So much for my theory about II and III John. Now let’s turn to I John, which, like the Gospel of John, was written by St. John the Apostle, a.k.a. the Beloved Disciple.

I John 3.1-3, RSV-CE

The Franciscan Church of the

Transfiguration, on Mount Tabor,

in the north of modern Israel.

See what love the Father has given us, that we should be called children of God;a and so we are. The reason why the worldb does not know us is that it did not know him. Beloved, we are God’s children now; it does not yet appear what we shall be, but we know that when he appearsc we shall be like him, for we shall see him as he is.d And every one who thus hopes in him purifies himself as he is pure.e

I John 3.1-3, my translation

See what kind of love the Father has given us, that we should be called God’s children,a and are. For this reason, the worldb does not know us—because it did not know him. Beloved, we are now God’s children, yet it has not yet been shown what we will be. We know that, whenever he is shown,c we will be like him, because we will see him just as he is.d And everyone who has this same hope in him sanctifies himself, just as he is sacred.e

Textual Notes

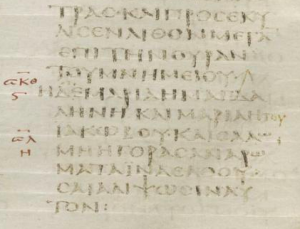

The end of II Peter and beginning of I John

in the 5th-cent. Codex Alexandrinus

a. ; and so we are/, and are: Translations of John’s writings tend to strike me as a little odd—perpetually shifting his emphases and altering his rhythm. I don’t know whether I’m actually detecting something weird about how translators handle the Johannine material, or if I’m imagining things because I like John. In any case, I half want to call the semicolon the RSV puts here a borderline incorrect translation, despite my usual liberality about punctuation. I think the idea was to give it a more natural English phrasing, but John isn’t conspicuous for his natural Greek phrasing (he is elegant, yes, but it’s a plainly non-native, un-Greek kind of elegance). The semicolon makes this into two thoughts; that isn’t how the sentence flows in the Greek; it’s a more continuous, natural progression from one phrase to the next.

b. world: We’ve mentioned the issue of the words for “world” before now. This one is κόσμος [kosmos], whose most literal meaning is “order, arrangement”; one is almost tempted to think of it as “the Establishment” in this context, but then, verbally, this is the same “world” that God “so loved … that he gave his only-begotten Son”.

Speaking of the cosmos, here is

the Milky Way

c. it does not yet appear … when he appears/it has not yet been shown … whenever he is shown: Fun tidbit: the verb here, φανερόω [faneroō], is the root of the term “Phanerozoic.” The Phanerozoic is the part of the fossil record that includes only the last 539 million years (ish), because it is only in that relatively recent time frame that we have any abundance of fossils (which are made by ζῷα [zōa], “living things,” hence -zoic) that are φανερός [faneros], “visible.” Creatures older than that were, as a rule, along the lines of microbes or sponges, leaving either no fossils or exceedingly hard-to-detect ones.

Anyway, “appear” and “show” are both possible translations of φανερόω (among a number of others, like “manifest”). I went with “show” because it’s one of the translations that allows for an appreciable distinction between the active and passive forms of the verb, and the passive form is used here. (Seriously, what’s the passive of “to appear”? Is it “to be appeared to,” which I guess equates with “to see”?) This seems to make Christ the object of a showing, implying a distinct agent who does the showing.

A 16th-cent. Russian ikon of the

Transfiguration.3

This tracks closely with the Father-centric theology of the Gospels, especially John—not that it is absent from Paul, either, as in the verse stating that “Christ was raised from the dead by the glory of the Father,” emphasis mine. The cloud on Mount Tabor suggesting the Shekinah, and the voice of the Father that it emits, also dovetail with this symbolism. The Transfiguration is one of the pericopes absent from the Fourth Gospel, yet it seems vividly present in this text, as it does in the prologue to John.

d. we will see him as he is/we will see him just as he is: The Greek hits a little more emphatically than the RSV’s English (in my opinion). Here again is that subtle shuffling of emphases, whose importance I’m probably exaggerating.

e. purifies … pure/sanctifies … sacred: “Purify” and “pure” are by no means incorrect translations of the verb ἁγνίζω [hagnizō] and the adjective ἁγνός [hagnos]. However, “pure” has the additional meaning “unmixed,” which I don’t believe the Greek root implies; and it has less in the way of specifically templar connotations than ἁγνός does. Words with the Latinate sanct-/sacr– root do the job better on both counts, in my opinion.

Part III to come!

Footnotes

1There are parts of, or versions of, this that annoy or amuse me (as well as other parts or versions that I think are perfectly reasonable). One of the things about it that makes me chuckle is that, usually, when a work is found to be pseudepigraphic—i.e., fraudulently passed off as being by a more respected author, usually a much older one—it’s because we have other works that are known to be legitimate by the author in question. So tell me, Academe: whomst exactly are y’all comparing the Gospel of Matthew or the Epistle of Jude to that makes you so confident they’re not by those guys? (The “case against” Matthew strikes me as especially ridiculous, since it seems, as far as I can tell, to consist in a more polished version of “nah.”)

2To be clear: I am not pulling a Luther—that is, questioning these works’ divine inspiration, or saying they should be expelled from the canon. I am only questioning whether their traditional ascription to St. John the Apostle is correct; lots of books aren’t by St. John the Apostle and are still Scripture, most of them actually.

3There used to be—and, I don’t know, perhaps still is—a custom in the Christian East that iconographers had to write an ikon4 of the Transfiguration as their first piece. This is because, in most Eastern Christian theology, ikons themselves are not regarded merely as artistic depictions of what happens to be a religious subject: they are channels of the light of the Transfiguration, where matter first began to participate visibly in divinity. The iconographer must therefore train his eyes to see according to that light, not only the visible kind.

4Ikons (at least of the Eastern kind) are properly “written” rather than “painted.” The distinction did not exist in Greek, both ideas being represented by the verb γράφω [grafō], but I understand that when the distinction was raised in English, the Orthodox were very clear which sense of the word they had in mind.