Series Table of Contents:

Introduction (what sacred/liturgical time is and why we have it)

The Canonical Hours (the Catholic “clock”)

The Former Holy Week (pagan antecedents of the week)

The Seventh Day (the Judaic week and the Sabbath)

The Revelation of the Octave (the Catholic week)

To Everything There Is a Season (Easter computus; fourfold interpretation of Scripture)

The Waxing of the Sun (the literal/meteorological year; the yearly allegory of the life of Christ)

⇒ The Waning of the Sun (the spiritual life through the lens of the year)

A Time to Get, and a Time to Keep (liturgical seasons in the Anglican Use)

The Moral Year …?

And when this epistle is read among you, cause that it be read

also in the church of the Laodiceans; and that ye likewise

read the epistle from Laodicea.

An ivory comb from Bavaria (ca. 1200),

featuring an abbreviated form of the “Tree

of Jesse” motif.

At first I wasn’t going to include a “moral interpretation” of the calendar; I couldn’t think of one. I did rather suddenly hit on an idea several days ago—one more like a second level of allegorical interpretation than a properly moral one, but something to fill the slot, anyway. I worked it out some, but I kept having this nagging feeling that posting it would be a bad idea, that it was open to dangerous abuses down the road.

I didn’t, and don’t, claim to see how that’s true. This could just be scrupulosity and paranoia talking. But, I don’t know, this felt like a hunch that needed to be listened to. And I couldn’t help but remember Joachim of Fiore at this juncture.

Joachim of Fiore was a twelfth-century Cistercian preacher from the south of Italy, and something of a “Bible codes” guy. His speculative doctrines got kind of out there; one of his major theories was that history was divided into three ages, corresponding to the Father (represented by the Torah), the Son (the age of the Church), and the Holy Ghost (whose age was yet to come but, Joachim calculated, imminent). He was widely known for his personal holiness, and acclaimed by some people as a prophet. However, the man himself disclaimed the title, and voluntarily submitted his writings to the judgment of the Church. No doubt it was partly for this reason that even when some of his ideas were condemned as heresy, he himself was never adjudged a heretic.1

Beatrice and Dante meet the souls of the wise

(including Joachim of Fiore) in the Sun in

Paradiso X; miniature ca. 1450, by

Giovanni di Paolo.

Well, some people latched onto the guy’s stuff excessively, as people will even if their The Guy tells them not to.2 The largest group influenced by Joachimism were the Fraticelli, a sect—or rather, a series of sects—derived from the Franciscan Order who believed the “age of the Holy Ghost” was imminent or had arrived, and usually that this or that pope (Boniface VIII, for example) was the Antichrist. On the whole, the millenarian beliefs of the Fraticelli were harmless, in the visible sense anyway.

The same cannot truthfully be said of the “Apostolic Brothers,” also called Dolcinians or Pseudo-Apostles. They took over the basic beliefs of the Fraticelli and added some good old-fashioned “Our leader (Brother Dolcino) is a prophet/the pope of this new Holy Ghost age and also we can have sex with whomever we like”; then, upset with the general populace of northwestern Italy for not taking their side, they went ahead and started murdering people and taking their stuff. After a few years, the ringleaders of the movement were caught and burnt by the Inquisition.3

Point is, I’m not interested in being the latest update of Joachim of Fiore! History doesn’t need that! So I’m gonna listen to my hunch and just move on.

But Christ Is All, And In All

(The Mystical Year)

Selection from Cristo Abrazado a la Cruz

[Christ Carrying the Cross] (1580),

by El Greco.

The mystical or anagogical meanings of Scripture are its applications to the individual soul on its journey into God. Here, I think, we are on firmer ground. Spiritually, I believe the analogues belowhold up reasonably well. Note that in three cases, sacraments rather than phases of life are listed. This is deliberate. The whole Catholic doctrine of the sacraments implies that, whether we subjectively experience them as such or not, they are in fact key events in our spiritual lives. (There are also three cases in which I think a solemnity, rather than the season it defines, most closely corresponds to the movements of the mystical way; this, I’m open to challenge about.)

- Advent: Our lives before baptism, especially as catechumens4

- Christmas: Baptism

- Epiphany: Confirmation

- Lent: sacramental Confession

- Eastertide until Ascension: life in the state of grace

- Eastertide after Ascension: The intermediate state5

- Pentecost: The Parousia (i.e., the Second Coming)

- Whitsuntide: The general resurrection and Last Judgment

- Trinitytide: Life in the new creation

The Ascension, depicted in the Rosary Basilica

at Lourdes, France; photo by Wikimedia

contributor Vassil.

Note that these correspondences are not just sequential. Baptism is described as being “born ἄνωθεν [anōthen]” i.e. “again” or “from above,” in John 3; the name and theme of Epiphany both have to do with God’s self-revelation, and the sealing of the believer with the Spirit in Confirmation aligns with his dovelike descent at Jesus’ baptism; the Holy Ghost’s descent on the Church includes certain symbolism associated with the Last Judgment, and St. Peter’s Pentecost sermon explicitly appeals to a prophecy set “in the last days”.

Obviously, the bulk of our earthly lives is spent in a recurring cycle of 4 and 5! Additionally, those of us baptized as infants aren’t going to remember 1 or 2, and the catechetical aspect of 1 will be postponed, usually to a period of our natural lives preparatory to 3.

Perhaps the most significant part of this “chronology,” to my mind, is how much of it is taken up by our life after the Last Judgment. It does give a certain fresh perspective on the rest, doesn’t it?

Again, the Kingdom of Heaven Is Like …

Crucifixion of Jesus of Nazareth (12th c.),

illustration by abbess Herrad of Landsberg

for the Hortus Deliciarum (“Garden of

Delights”), an encyclopedia.

I wonder to what extent the recognized structure of the contemplative or mystical life is also presented, cryptically, in the liturgical year. Both within and outside the Christian faith, a tripartite sequence of mystical growth is widely recognized: first, a period of purification, normally characterized by arduous ascesis of various kinds (fasts, vigils, etc.); then, a period of enlightenment, in which intellectual problems and mysteries are disclosed; and finally, a period of accomplished, if transitory or incomplete, union. The monastic tradition of the Church recognizes these three basic stages of mysticism, and finds that they are typically separated by two sub-phases (which I gather are normally more intense and briefer than the main stages), known as “nights.” They go like this:

I. The Purgative Stage

The Night of Sense

II. The Illuminative Stage

The Night of the Spirit

III. The Unitive Stage

I believe the terminology, at least for the “nights,” comes from St. John of the Cross. Let’s discuss the whole schema in just a bit more detail.

John of the Cross (1656), attributed

to Francisco de Zurbarán.

When we embark on the deliberate pursuit of holiness—that is, when we wholeheartedly make intimacy with God our most important goal—the first stage of growth is spent in cleansing ourselves from corrupting habits and attachment to occasions of sin. This is followed by a purgation (the “night of sense”) that falls upon us from without, so to speak, which detaches us from dependence on our merely natural motives for pursuing intimacy with God.

In the illuminative stage, God speaks directly to the heart. I gather that genuine visions and locutions, if they occur, are likeliest to come in this stage—however, I’m not sure how firm a rule this is. Another, more profound purification, the “night of the spirit” or “dark night of the soul,” follows. This often feels like an attack to the adept, though St. John of the Cross explains in his eponymous book that it is in truth a form of far deeper enlightenment: Its apparent darkness is in reality something more like being temporarily dazzled by the sun after time spent underground.

Finally, in the last stage, the soul increasingly enjoys union with God, usually of an intermittent nature. I get the impression that, regardless of the adept’s age, this generally signals that death will come within a few years, though again I’m not entirely clear or certain here.

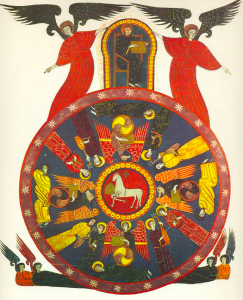

Vision of the Lamb, the cherubim, and the

twenty-four elders from the 8th-c.

Apocalypse of Beatus of Liébana.

This structure does feel natural to me; however, interestingly, I’m having a hard time correlating it to the liturgical year. The Lent-Eastertide-Trinity part tracks well enough, especially if we treat the Passion as the night of sense and the novena before Pentecost as the night of the spirit. (I think I picked this idea up in a book I read by Fr. Reginald Garrigou-Lagrange—at any rate, I know it would never have occurred to me to align the Cenacle’s time waiting for the descent of the Spirit with the dark night of the soul.) But that’s only a portion of the year, and leaves the whole Christmas cycle right out.

I have two more topics to cover—one on the specifically Anglican seasonal structure that I promised we’d come back to, and one on the relative ranking of the difference observances on the Church’s calendar. However, those are basically glorified (and nested) footnotes, and this post is long enough, so they can wait!

Footnotes

1Another name for this distinction is material versus formal heresy. Material heresy is being seriously wrong about a point of doctrine—something that can happen quite innocently; there are canonized saints, doctors of the Church even, who have held materially heretical beliefs. Formal heresy is different (don’t think of it in terms of “mere formalities,” but in terms of “the Platonic form of a thing”). It is a rebellious refusal to accept that one’s error is an error: There is an element of dishonesty and disobedience at work in it, some level on which the formal heretic really knows better than to be stubborn about this. Formal heresy takes what may have been a mere mistake and turns it into a deliberate lie, usually told first of all to oneself. Willing, ready surrender to the judgment of the Church is therefore the spiritual opposite of formal heresy.

2The late Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie’s reaction to the Rastafarian movement proclaiming him divine springs to mind—not the sort of pastoral conundrum faced by most Orthodox Tewahedo believers, or indeed most Christians of any denomination.

3Okay, not technically by the Inquisition; technically, the Inquisition never burned anybody, or tortured anybody, or any of that stuff—all those things were technically done to heretics by the secular arm, either as lawful punishment for heresy (which was a capital civil crime in most of Europe) or as part of the (again, lawful) interrogation process, since heretics were always presumed to have accomplices. But no one in his senses can seriously argue that this makes inquisitors, or the Church in general, innocent of these things. If the Church had (1) objected to the institution of heresy laws and the authorization of torture when they were proposed, (2) regularly protested against these things while they existed, (3) done everything in her power to prevent accused persons (regardless of their guilt) from being victimized by these policies, and (4) been an active force in the repeal of the heresy laws and the abolition of torture—then, on those four conditions, the Church could disclaim responsibility for the horrors we associate with the name of the Inquisition. As history actually went down, however, the Church is very justly and proportionally blamed for her role in the treatment of heretics, Jews, and those accused of witchcraft over the thirteenth to eighteenth centuries (especially during the witchcraft mania of the sixteenth and seventeenth).

4Given that many Christians are baptized in infancy, this correspondence won’t be exact; however, even in ancient times, instruction did continue after baptism (for the first year especially—persons in this part of their religious life were known as neophytes).

5In Christian terminology, “the intermediate state” refers to the period between an individual person’s death and the general resurrection, which will take place at or shortly after the Parousia (i.e. the Second Coming). Catholics believe that those who die in a state of grace will spend the intermediate state in heaven, either with or without a preparatory rehabilitative period in Purgatory (which is not really a “separate place” from heaven—”heaven’s mud-room” would be a better analogy).